No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, and Order for basis; Progress for aim.”

F.J. Gould, The Life-Story of a Humanist (1923)

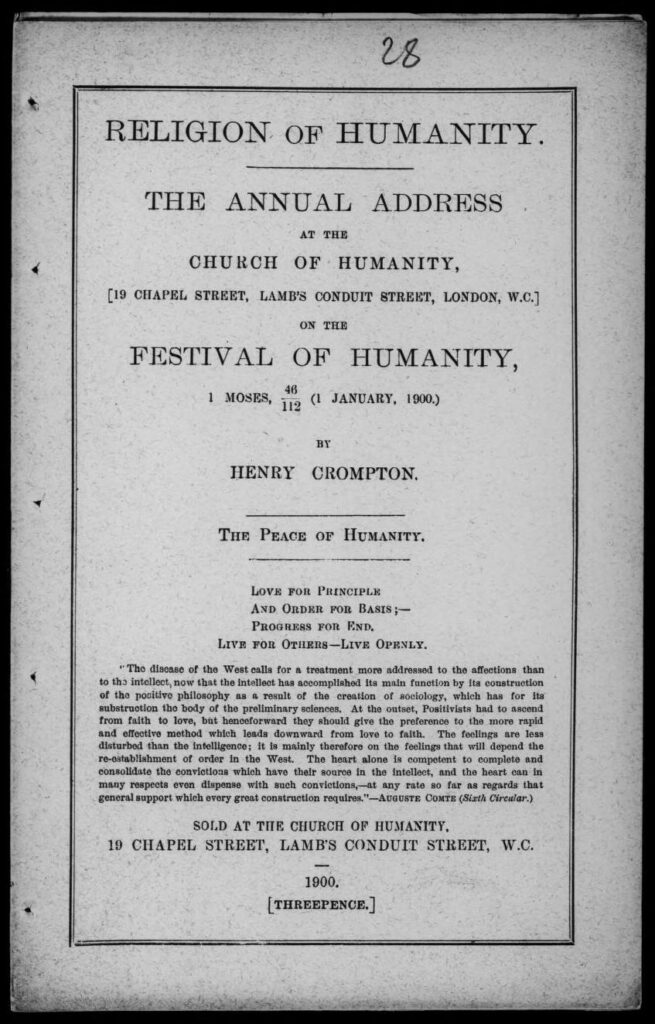

The positivist ‘Church of Humanity’ was established by philosopher Richard Congreve at 19 Chapel Street (now 20 Rugby Street) in Bloomsbury in 1870. A devotee of Auguste Comte, Congreve sought to celebrate the achievements of humankind through secular ritual, predating later efforts by the Ethical societies. The freethinking Harriet Martineau had played a significant role in popularising Comte’s ideas in England, with her 1853 translation of his Cours de philosophy positive, and the Bloomsbury location provided the first proper home for the London Positivist Society, founded three years earlier.

Initially described as the Positivist School, Chapel Street hosted meetings of the Society, secular ceremonies in the positivist tradition, as well as a library and a school. Following a break with others in the group in 1878, Congreve was left to run the centre alone, the breakaway contingent founding a new hall at Fetter Lane. From this point onwards, Congreve introduced increasing levels of ritual, of the kind which led some – notably T.H. Huxley – to decry positivism as ‘Catholicism minus Christianity’. Congreve eventually renamed his site the ‘Church of Humanity’.

Following Congreve’s death in 1899, leadership of the Church was taken on by Henry Crompton, a Liverpool-born barrister, whose brother founded the Liverpool Church of Humanity. Crompton, like his predecessor, lectured on social and moral subjects at the chapel, and was also active in efforts towards reform. His Dictionary of National Biography entry notes that he:

sedulously applied his principles to public questions. He was always active to protest against international injustice and the oppression of weaker races. He served on the Jamaica committee, formed to prosecute Governor Eyre in 1867; worked for the admission of women to the lectures at University College; was untiring in efforts for the improvement and just administration of the criminal law; and gave strenuous and useful support to the trade unions in their struggle to reform the labour laws.

In spite of Crompton’s efforts, the popularity of positivism and of the Church of Humanity declined in the early decades of the 19th century. The separate factions of the London movement reunited in 1916, and were based at the Chapel Street premises until 1932, when the Church of Humanity closed for good.

You can always appeal to common decency, which the vast majority of people believe in without the need to tie […]

The one thing in which I am interested wholly and completely is the getting to know something about human society […]

[Ouida’s] exaggerated enthusiasms made readers smile, but they also made them think. It would be difficult to overstate the effect […]

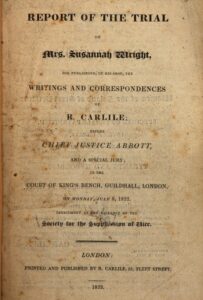

I have no desire… to bring the religion or the laws of this country into contempt, although I am a […]