It lies within our power, if we so desire it, to make the familiar world we inhabit more worthy of habitation by beings who aspire to be rational and are capable of love.

Philosophy and the Physicists, 1937

Susan Stebbing was a philosopher, teacher, and Ethical Union president, who overcame a sickly childhood to become an influential thinker and educator. Her membership, and presidency, of the Ethical Union (today Humanists UK) epitomised her belief that the high-minded pursuits of logical philosophy could be applied to social problems and practical efforts toward positive change. This, and the compassion and active care for others which characterised her, secure Stebbing’s legacy as a consummate humanist.

Lizzie Susan Stebbing was born in London on 2 December 1885, the youngest child of six born to Alfred Charles Stebbing, a fish merchant, and Elizabeth (née Elstob). She was educated first at James Allen’s Girls’ School, Dulwich, before going up to read History at Girton College, Cambridge in 1904.

It was a chance introduction to F. H. Bradley’s Appearance and Reality which led Stebbing to change focus to Moral Sciences: course of study covering moral philosophy, logic, and psychology. On leaving Cambridge, she studied for her MA at the University of London, presenting a thesis on Pragmatism and French Voluntarism in 1912. From 1911-24, she remained a visiting lecturer in Moral Sciences at Girton and Newnham Colleges, also lecturing for two years at King’s College, London 1913-5.

In 1915, Stebbing (alongside her sister, Helen, Hilda Gavin, and Vivian Shepherd) took over the Kingsley Lodge School for Girls in Hampstead, where she taught history. Simultaneously, Stebbing worked at Bedford College, London, becoming a full-time lecturer in 1920, a reader in 1927, and professor in 1933: the first woman in the UK appointed to a full professorship in Philosophy. She remained at Bedford College until her death, aged 57, in 1943.

Stebbing’s obituary in Nature, emphasised her teaching and writing as ‘strenuous and clear-headed’:

Her lectures were full of life. In discussion with her one could not expect to sit about it warm air – a stiffish breeze was usually blowing. But those who were given her vigorous teaching must, I think, have felt very great kindness and patience behind the sharp raps they were expected to stand up to in their training.

John Wisdom

Stebbing believed in the power of clear thought and clarity of language to produce real change. Her argument that an understanding of how language could be used to mislead and manipulate could empower ordinary people, crystallised in her 1939 work Thinking to Some Purpose, published on the eve of the Second World War. The book’s full title was Thinking to Some Purpose: A manual of first-aid to clear thinking, showing how to detect illogicalities in other people’s mental processes and how to avoid them in our own. The book was dedicated to A. F. Dawn, another notable humanist, who had founded the University of London Ethical Society in 1926. Siobhan Chapman has since written that:

Driven by the social and political crises of the mid twentieth century, [Stebbing] argued that ordinary people should be empowered to harness the forces of close linguistic awareness and logical argument to confront uses of language designed to influence their opinions.

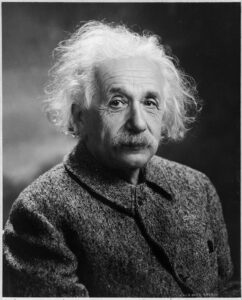

Stebbing’s emphasis on the practical, positive uses of philosophy was deeply humanist, and characterised the stance of the Ethical movement from its origins in 1876: applying moral ideas to live better lives. She had been influenced in part by fellow humanist and former Ethical Union president G.E. Moore, who advanced a ‘common sense’ approach to language and philosophy. In Thinking to Some Purpose, and Philosophy and the Physicists (1937), Stebbing argued against confusing and misleading language – the kind often used by politicians, scientists, and philosophers – and for the real life relevance of logic and thoughtful enquiry for the wider population, especially in engaging with contemporary issues.

Stebbing was president of the Aristotelian Society in 1933, the Mind Association in 1934, and the Ethical Union in 1941, as well as being an honorary associate of the Rationalist Press Association. She was active socially, and engaged politically, including as a supporter of the League of Nations Union. She was also actively involved in assisting refugees from Germany and Nazi occupied countries, donating time, money, and influence to ensuring the safety of both adults and children.

As is one’s philosophy, so is one’s way of life.

L. Susan Stebbing, Ideals and Illusions

In her writings she was witty, clear, and engaging; in her teaching ‘strenuous’ but kind; and in her personal life, Stebbing was devoted to applying all of these qualities to securing the wellbeing and freedom of others. She vehemently emphasised the value of careful reasoning and reflective thinking, not just for philosophers but for everyone. In Ideals and Illusions (1941), she distinguished between motivating ideals, and dangerous illusions, the latter of which – particularly in politics and religion – could enable injustice and inequality. In all of this, Stebbing worked to encourage people to think for themselves, and apply their conclusions to making a better world for everyone.

In my opinion our most urgent need to-day is to know clearly what are the things that belong to our happiness. To know this is to begin to formulate a way of life.

L. Susan Stebbing, Ideals and Illusions

How strange is the lot of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose […]

There is nothing to fear from Gods, nothing awaiting us in death; good can be obtained, evil fortune can be […]

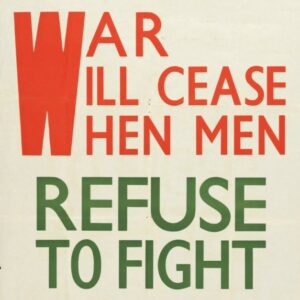

We are living in critical days. It is not enough to desire peace or to talk peace. We must make […]

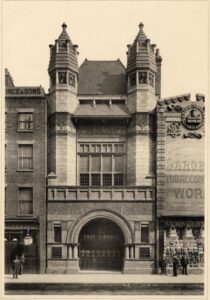

Bishopsgate Institute was built ‘for the benefit of the public’ in 1894, intended to provide opportunities for education and recreation […]