Dr Alice Vickery was a humanist, physician, and devoted champion of women’s reproductive rights. Her tombstone inscription remembers her as ‘an original thinker and ardent feminist,’ and she is believed to have been the first woman to pass the examination with the British Pharmaceutical Society.

An ethical society member and secularist, Alice Vickery lived her humanism in work and life, challenging Victorian social norms and championing the rights of everyone to greater freedom and choice.

Alice Vickery was born in Swimbridge, Devon, the fifth child of piano maker and organ builder John Vickery. Initially schooled close to home, she later joined her family in London and became a pupil teacher, likely at a school in Camberwell endowed by the businessman and secularist William Ellis.

From 1869, Vickery attended the Ladies’ Medical College, a ‘controversial establishment’ providing midwifery training. Here she met her lifelong partner Charles Drysdale, whose name she later adopted in spite of their shared objection to the institution of marriage. Gaining her midwifery certificate in 1873, she registered with the British Pharmaceutical Society – through which women could attend courses and take examinations, but to which they were denied membership. Vickery was said to be the first woman to pass the examination.

In 1873 Vickery travelled to France in order to study medicine at the University of Paris, no British medical schools admitting women at that time. When the London Medical School for Women (LMSW) was established in 1874, Vickery quickly registered, though it was not until 1877 – when her existing qualifications were refused recognition by the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland – that she returned to London and attended the LMSW.

That same year, Vickery gave evidence in the trial of Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, who had been charged with obscenity for publishing Charles Knowlton’s The Fruits of Philosophy, which advocated birth control. She was subsequently active in the Malthusian League, as both a vice-president and council member, but withdrew from public association as a result of the LMSW’s reluctance to be associated with the group. In 1880, over a decade after first entering training, she became a licentiate in midwifery.

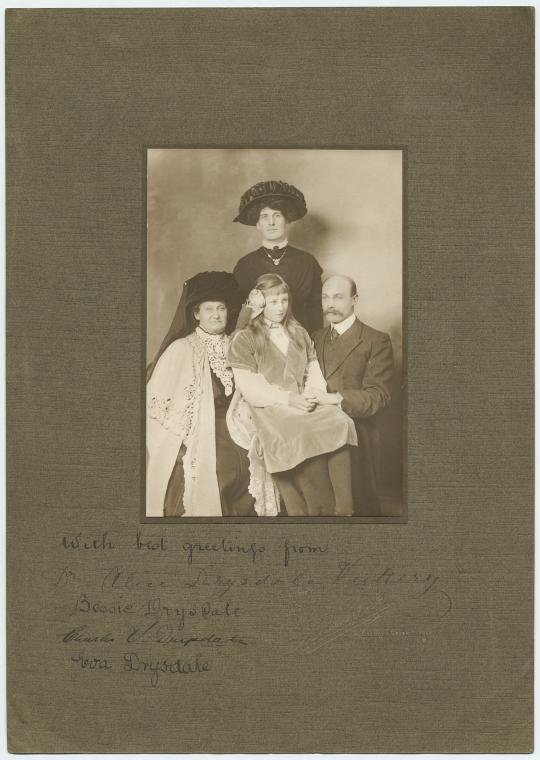

In defiance of rigid Victorian concepts of morality, Vickery and Drysdale never married, and had two sons together before they lived underneath the same roof. It was not until 1895 that the couple settled in Dulwich, where they let it be assumed they were married. Their elder son, Charles Vickery Drysdale, would later be a founding member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, alongside two other notable humanists: Laurence Housman and H.N. Brailsford.

Vickery’s brother, John Leah Vickery, was also an active member of the ethical and freethought movement, an acquaintance of Charles Bradlaugh, and part of the community of South Place for over four decades. His 1928 obituary in the Ethical Record describes his ‘kindly disposition… allied with a keen enjoyment of the humorous’: a ‘friend to all advanced thought’. In his will, he left significant bequests to the South Place and South London Ethical Societies, as well as the Rationalist Press Association and Secular Society.

A secularist, feminist, and freethinker, Alice Vickery maintained an active involvement in a number of progressive causes while practising as a doctor. She regularly lectured on the need for birth control, and joined the campaign against the Contagious Diseases Acts. In the 1890s, Vickery was involved in the Legitimation League, as well as the National Society for Women’s Suffrage, the Women’s Social and Political Union, and the Women’s Freedom League. She was an active member of the Women’s Group of the Ethical Movement, and of the ethical societies more broadly, where she would have found support for her efforts toward reform.

Vickery continued to actively champion the causes she believed in until the very last days of her life, including as president of the Brighton branch of the Women’s Freedom League. She died on 12 January 1929, aged 84. Her obituary, reprinted in the Ethical Record, was written by fellow Women’s Freedom League activist Edith How-Martyn, and described her as ‘above all a feminist’.

How-Martyn wrote that Vickery’s ‘firmly rooted feminism’ led her to see women’s rights to reproductive choice ‘as fundamental to their personal freedom and the keynote of women’s emancipation’, but noted too that she ‘was not as well known to the present generation of feminists as she deserved to be.’ Similarly, though Vickery’s humanism shone through in her faith in science and tireless advocacy of human rights, she remains a little known freethinker.

Alice Vickery’s willingness to question the social standards of her time, to push for her own advancement in medicine, and to champion women’s rights to social and political freedom, demonstrate a pioneering spirit and deeply humanist approach to life. Her example forms part of a long tradition of humanist involvement in progressive reform, particularly in areas surrounding birth control and reproductive rights, which continues in the movement today.

Read more

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Alice Vickery [Drysdale]

Obituary by Edith How-Martyn: The Women’s Leader (LSE Digital Library)

While there is much that we do not know, humans are responsible for what we are or will become. No […]

The National Portrait Gallery is an art gallery primarily located in London but with various satellite outstations located elsewhere in […]

To say that “God moves in mysterious ways” is to put up a smokescreen of mystery behind which fantasy may […]

Dr Alice Vickery was a humanist, physician, and devoted champion of women’s reproductive rights. Her tombstone inscription remembers her as […]