The Arts

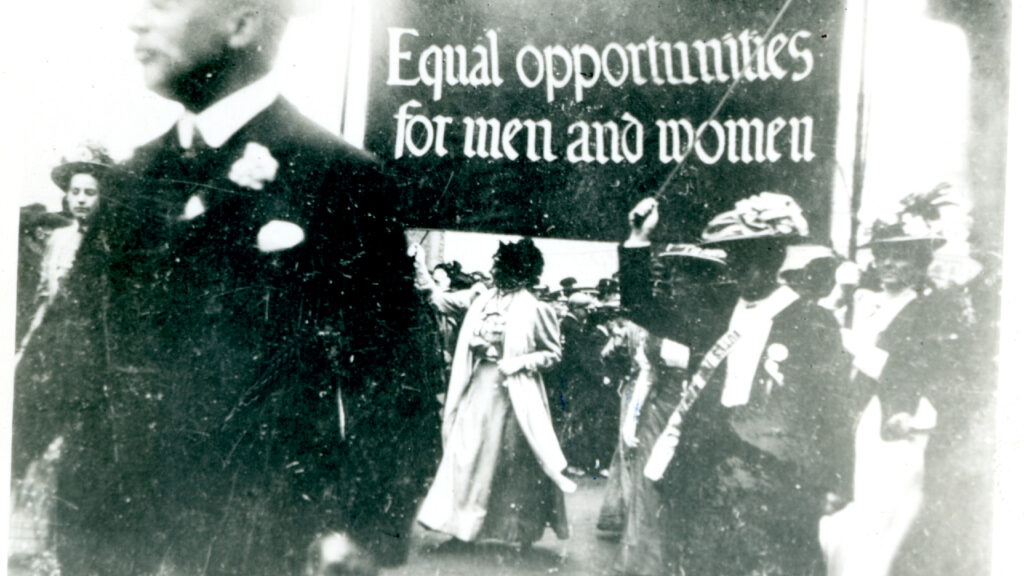

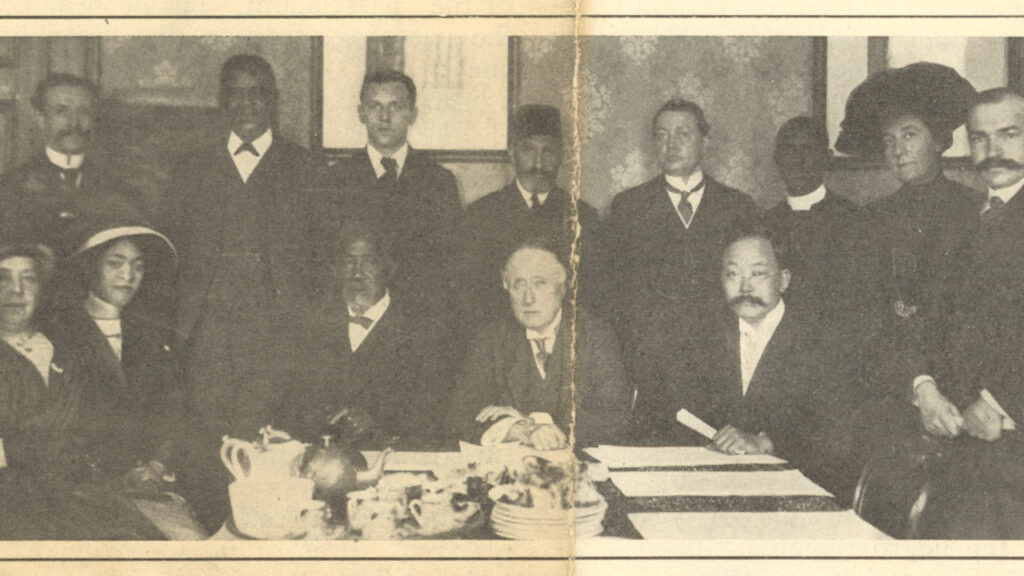

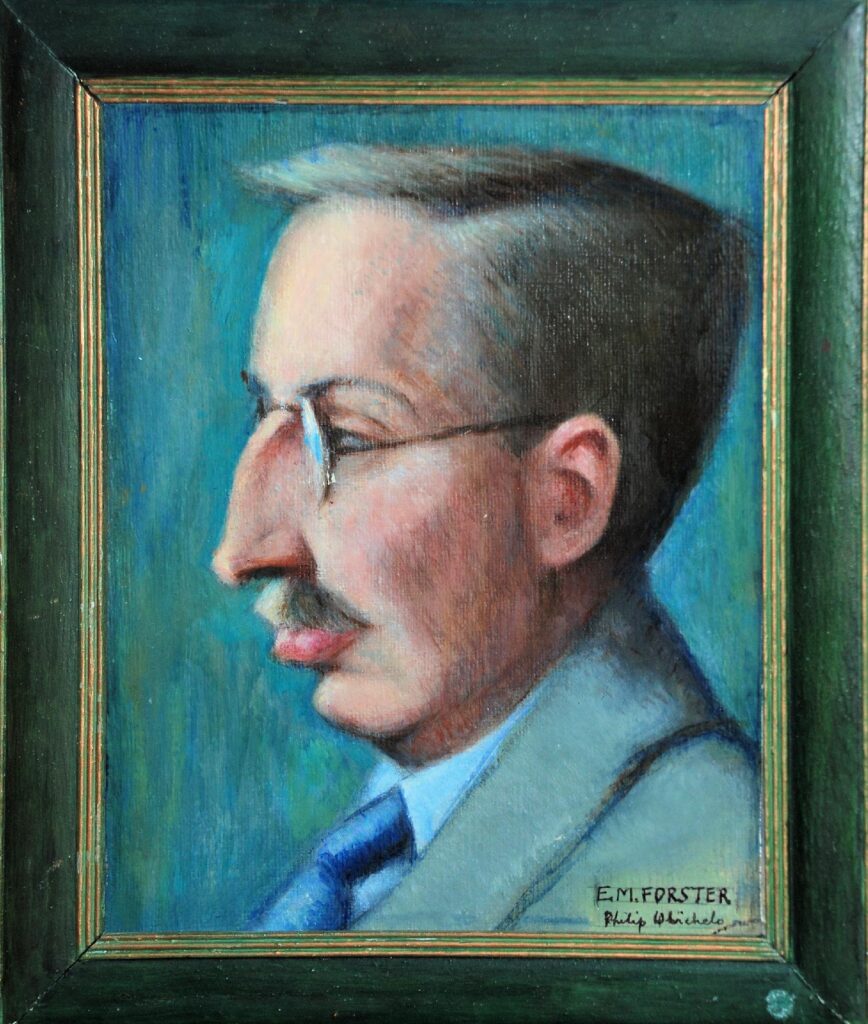

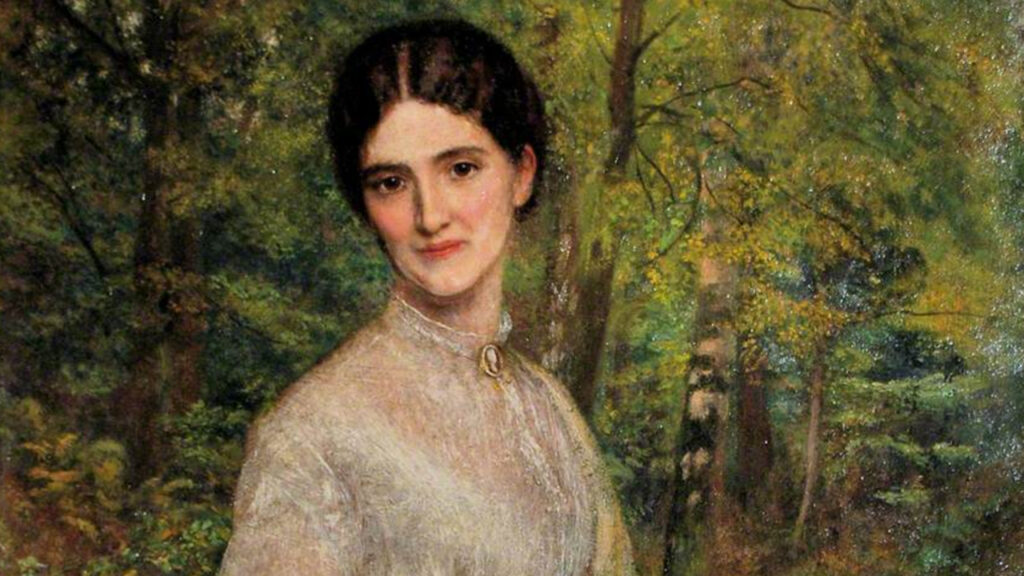

Many artists, writers, actors, and musicians have identified as humanist, or expressed a worldview very much aligned with humanism. From composers like Eliza Flower and Benjamin Britten, to writers like George Eliot and Claude McKay, to lesser known artists active in the early Ethical movement, like Ernestine Mills and Charles Kennedy Scott, humanist history is full of those who have celebrated life, and explored emotion, through the creative arts.

See all posts related to the arts.