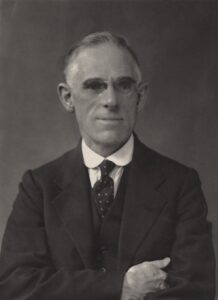

A.J. Ayer (1910-1989)

( 29 October 1910 - 27 June 1989 )

( 29 October 1910 - 27 June 1989 )

In common with other humanists, I believe that the only possible basis for a sound morality is mutual tolerance and respect: tolerance of one another’s customs and opinions; respect for one another’s rights and feelings; awareness of one another’s needs.

A.J. Ayer, introduction to The Humanist Outlook (1968)

A.J. Ayer was a philosopher, activist, and president of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) 1965-1970. As well as an eloquent promoter of the values of humanism and secularism, Ayer was a devoted champion of compassionate, progressive reform in diverse areas of society. He was president of the Homosexual Law Reform Society, and the Agnostics Adoption Society, and chair of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination in Sport. Ayer embodied the values of humanism he defined, giving them expression in statements – and causes – still central to Humanists UK today.

Alfred Jules Ayer was born in London in 1910 into a wealthy European family. A solitary child growing up, Ayer spent much of his formative years at boarding school, eventually studying at Eton College. After proving a bright, inquisitive, and charismatic student at Eton, he obtained a scholarship to study classics at Christ Church college, Oxford. Despite graduating with first class honours, Ayer never quite clicked with the prevailing philosophical milieu at Oxford, which he felt to be outdated.

On the advice of his tutor Gilbert Ryle, Ayer spent the winter of 1932-33 in Vienna, where he was introduced to the meetings of the Vienna Circle. This was a group of scholars who championed empiricism and logic, summing up their position as ‘logical positivism’. They wished to see philosophy become more scientific and more subject to the demands of logic. Ayer found this environment fascinating and inspiring, and upon returning to England to take up a teaching position at Christ Church, he began writing his own contribution to this movement. In 1936, Ayer published Language, Truth and Logic. The precocious young 26-year-old’s work sent shockwaves through traditional British academia, formulating as it did the ideas of the Vienna Circle into English for the first time.

The book’s main thesis was the verification principle, which held that every possible statement is either verifiable or unverifiable, and that only the former hold any meaning. Verifiable statements can be either truths based on empirical observation, or truths of logic and mathematics. Any other statements, including those rooted in metaphysics, ethics or religion, cannot possess a truth-value, and are therefore meaningless. The statement ‘God is good’, for example, is neither empirically verifiable nor a self-evident logical truth, so therefore falls short of both criteria for verification and is, to the logical positivist, nonsense. Such statements may accurately express the speaker’s own personal preference, but Ayer maintained that they are of ‘no factual significance’.

Language, Truth and Logic would prove to be Ayer’s defining work, and he spent a large part of the rest of his career articulating its arguments, refining them and helping to introduce philosophy in general to a wider audience. After serving as an officer with the Welsh Guards during the Second World War, Ayer held numerous teaching posts, heading philosophy and logic departments at University College, London and later back at Oxford. Alongside his teaching and writing commitments, Ayer used his position to bring philosophy to the general public. He believed, like his colleague and friend Bertrand Russell, that philosophy should be accessible and enthused with a sense of brightness. He appeared on national television to discuss philosophy, among a host of other subjects. He was also an active voice in a number of political and social campaigns. In addition to his role as president of Humanists UK from 1965-1970, he was a vocal critic of the Vietnam War and fronted the Homosexual Law Reform Society. A man with an incredible range of interests, he was every bit as at home at grand Oxford banquets as he was on the terraces at White Hart Lane, home stadium of his beloved Tottenham Hotspur. An avid football fan, he was for a time the Chair of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination in Sport.

Humanists think: that this world is all we have, and can provide all we need; that we should try to live full and happy lives ourselves and, as part of this, help to make it easier for other people to do the same; that all situations and people deserve to be judged on their merits by standards of reason and humanity; and, that individuality and social co-operation are equally important.

A.J. Ayer

Throughout his life, Ayer was committed to truth, reason and meaning. He had no time for religion, believing it to be literally nonsensical. As such, he lived his life on firmly humanist principles, and a life of great warmth and depth was the result. A signatory to the Humanist Manifesto, in 1968 he edited The Humanist Outlook, a collection of essays by a number of prominent secularists. He went further than most in dispelling the myth that religion and morality are intimately connected, not only in his academic writings, but also in the way he lived his life. All who knew him attested to his passion, charm and humour, and Ayer demonstrated just how rich and meaningful a life devoid of religious superstitions can be.

Essentially, I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life. Whether […]

Many human beings are sensible and friendly and kind; able to combine together to carry out wise policies. It is […]

Harry Snell was a socialist politician and campaigner, a devoted advocate of the Ethical Movement and a key figure in […]

William Pirrie Barbour was a classicist, codebreaker, teacher, and activist. A rationalist and humanist, Barbour championed integrated education in his […]