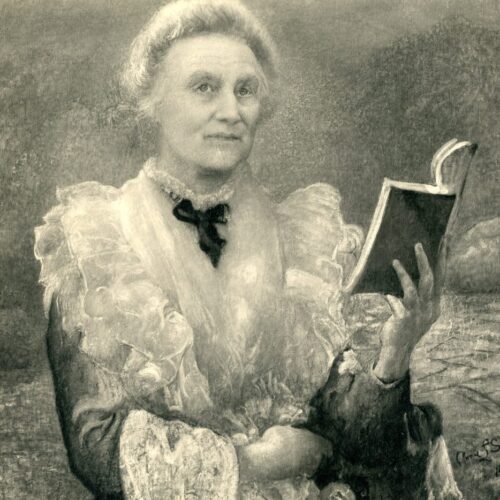

Alice Woods was an educationist and headteacher; a member of the Hampstead Ethical Institute, and a proponent of moral education. As well as advocating for co-education and the professional training of teachers, Woods advanced progressive ideals of compassion, innovation, and understanding in the teaching of young people. Like many other humanists of her time, Woods’ central focus was the adequate preparation of the next generation for living compassionately and cooperatively with one another, developing a sense of responsibility and morality in the light of new understandings of the world.

Alice Augusta Woods was born in Walthamstow, Essex on 6 August 1849, the daughter of a stockbroker. Educated at home, and initially teaching in a school run by her cousin, she entered Girton College, Cambridge in 1877 at the age of 28. There she studied for the Moral Sciences Tripos (politics, philosophy, and economics), passing the examination in 1880 alongside friend and fellow educator E. E. Constance Jones. In her reminiscences, Jones describes receiving their results pencilled on a note sent by their mistress to Henry Sidgwick inquiring as to their success in the examination. At the time, women were not awarded degrees by the University, and examination was dependent ‘entirely on the goodwill of the examiners’. Woods obtained a second class.

Woods taught at various schools before, in 1884, she was appointed headmistress of Bedford Park School in Chiswick. Newly founded, the school was co-educational and non-sectarian; this absence of religious instruction rankled some in the community, who established a rival school in the area. Woods remained there for eight years, strengthening her belief in the benefits of co-education, and developing a reputation for expertise in this area.

From 1892-1913, Woods was the Principal of the Maria Grey College, London, which – on its foundation in 1878 – had been the first to offer professional training for secondary school teaching. Here, she was known as ‘administratively casual but educationally adventurous’, and devoted to improving the standard of students’ work. In 1897, she was part of the original conference that led to the establishment of the London School of Ethics and Social Philosophy by the London Ethical Society and their supporters. By 1900, she was lecturing alongside other key figures in the Ethical movement for the Royal Institute of Philosophy. In the earliest years of the Union of Ethical Societies, formed in 1896, Woods lectured on a number of occasions, joining other humanist educationists active in the promotion of moral – rather than religious – instruction in schools.

Alice Woods presented a paper at the First International Moral Education Congress in 1908, urging the importance of literature. In discussions, she ‘urged that teachers should seize the opportunities given when children come to them with moral problems, and let the children regard them as fellow-strugglers.’ This open, gentle, and progressive attitude towards young people was also evident in Woods’ essay ‘Unhand Me, grey-beard loon!’, which appeared in the 1920 edition of Education for the New Era (the journal of the progressive New Education Fellowship – today the World Education Fellowship). In it, she encouraged readers to recognise the radically transformed world of the new generation and, making reference to the First World War, to acknowledge her own generation’s failure to bring about the kind of world young people might strive to emulate. ‘The youth are groping for their right place in the world,’ she wrote, ‘for a pathway along which they might travel for the world’s good’:

They are questioning our education, our creeds, and our morality, and strong criticism is the order of their day. Perhaps we are a little afraid to let them think lest the sceptre should depart from us, but our sceptre has to pass into their hands, and one of our most important duties is to provide them with the means for freedom of thought as well as freedom of action.

This desire to face the problems of the world head-on, and to educate young people for living well and according to values they could carve out for themselves, was central to Woods’ work and philosophy. She died at her home on 7 January 1941, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium.

‘The one foundation of all true consideration each for each is a deep, wide, unceasing sympathy.’

Alice Woods’ humanism was evident not merely in her membership of the Hampstead Ethical Institute, but in the foremost values of her life and work: informed scepticism, unceasing compassion, and unselfish service to humankind. Her advocacy of co-education was strongly rooted in a belief that teaching boys and girls together would best prepare them for living well in the world, a philosophy seen too in her active promotion of moral instruction. Efforts towards inclusive and honest education, epitomised by Woods and her colleagues in the early Ethical movement, remain central to the work of Humanists UK today.

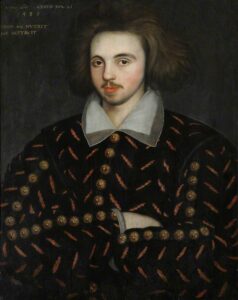

I count religion but a childish toy,And hold there is no sin but ignorance. Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta, […]

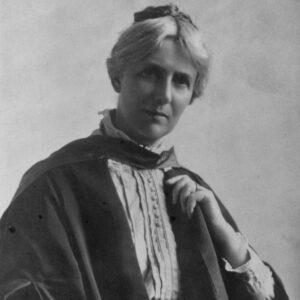

Millicent Mackenzie was a pioneering educationist and suffragist, who – alongside her husband, John Stuart Mackenzie – gave significant support […]

Theodore Besterman… was one of the most remarkable of the long line of remarkable people who have given their support […]

Against the militarist totalitarian state, I have striven. For the freedom of the human spirit to develop under the kindly […]