He was a great humanist whose religion lay in loving his fellow men and trying to serve them.

These are the words of Scottish Labour politician Jennie Lee, and were written following the death of her husband, the prominent socialist and architect of the National Health Service Aneurin Bevan. Bevan had not led a quiet life. At every corner, he proudly and passionately stood up for what he believed in, providing a voice for working-class Britain and fighting against economic and social injustice. Even his most ardent political opponents (of whom he made many during his career, including several on his own side) admired his tenacity, intelligence, wit, dedication, and compassion. Jennie Lee perfectly encapsulated her husband’s sincere humanist convictions, evidenced through his commitment to building a fairer, more peaceful society for all to share in.

Aneurin Bevan was born in Tredegar, a working-class mining town in South Wales, in 1897. The mining industry was a huge part of his young life; his father and grandfather both worked in the mines, as did a significant proportion of Tredegar’s workforce, and after leaving school at the age of thirteen, Bevan himself began working at the local colliery. By 1916, Bevan was already the chairman of his local Miners’ lodge and was heavily involved with union activities. He protested against Britain’s involvement in the First World War, and fought against unsafe and unjust practices in his industry. His frequent agitation ensured he constantly fell out with his employers and he never stayed in any one job for very long. His role within the trade union network saw him rise to prominence during the 1926 general strike, and he quickly became one of the most influential and prominent figures in the South Wales workers’ movement.

Despite leaving school early, Bevan was very bright, and had always been fascinated by history and politics. After spending time as a Labour councillor in Monmouthshire, Bevan was elected to Parliament as the Labour representative of the Ebbw Vale constituency in 1929. He very quickly established a reputation as a fierce orator and activist. Politicians from all sides found themselves on the receiving end of Bevan’s pointed rhetoric, from Winston Churchill and compatriot David Lloyd George to figures in his own party such as Ramsay McDonald. This dissatisfaction with the political mainstream saw him briefly flirt with Oswald Mosley’s movement in 1931, yet Bevan chose ultimately not to abandon the Labour party for Mosley’s New Party, and washed his hands of the association as Mosley’s movement veered to the far right. Still, Bevan was never a settled ally within the Labour ranks, and didn’t shy away from standing up to his party. He was even expelled from Labour for a short time for his involvement with attempts to unite all parties of the left. Though brought quickly back into the fold, conflict was to be a theme of Bevan’s political career.

Though a prominent critic of Churchill’s government during the Second World War, Bevan believed the War offered the chance for a new start for society. His optimism going into the post-war election of 1945 proved to be well-placed, as Labour won a landslide victory and Bevan entered the cabinet as minister of health and housing. He was to play a key role in the implementation of the ‘Welfare State’; a series of social reforms aimed at rebuilding a nation still reeling from a long and brutal conflict. He oversaw the construction of over 1 million, high-quality new homes, an impressive enough achievement, but the innovation he is most widely remembered for was the creation of the National Health Service. Bevan overhauled the nation’s muddled and localised healthcare provisions and introduced a publicly-funded, fully accessible, free at the point of use government-run institution. Although he was forced to make some initial concessions to healthcare professionals to bring them on side, the NHS very quickly became a cornerstone of national identity and a treasured institution, which it remains to this day.

Nye Bevan believed that ‘no society can legitimately call itself civilised if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means’. The NHS encapsulates everything which Bevan stood for, and was the culmination of a life devoted to improving the lives of men and women across the country. He may have made a number of political adversaries, and his approach may at times have been counterproductive to his cause, but what cannot be denied is the strength of his convictions. Bevan, a lifelong atheist and humanist, felt a deep affinity with his fellow man. He saw the innate dignity which all humanity shares, and always sought to protect those rights and opportunities which we are afforded by our common, universal kinship with each other, regardless of wealth or background.

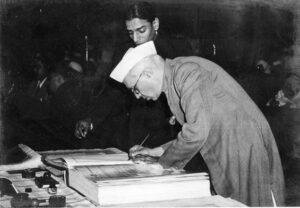

Main image: Aneurin Bevan by Howard Coster, 1943 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Essentially, I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life. Whether […]

Oh what a tissue of inconsistencies are the dogmas in which we have been reared! Emma Martin, God’s Gifts and […]

The Liverpool Ethical Society was founded in 1904, and in 1912 Liverpool became home to one of only a handful […]

The big problem of today is how shall we adjust these tremendous new forces so that they can be harnessed […]