Antony Flew was a British philosopher and was, for much of his life, a renowned atheist and eloquent proponent of humanism. He was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, a regular contributor to the New Humanist, and a longtime Vice President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK). Flew’s writings, including God and Philosophy (1966) and Atheistic Humanism (1993), gave persuasive articulation to atheist ideas, winning academic and popular appeal, and influencing a generation of humanist thinkers.

The son of the Methodist minister and theologian Robert Newton Flew, Antony Flew did not follow in his father’s footsteps, and as a teenager he reached the conclusion that God did not exist. After enlisting in the Royal Air Force and working at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, Flew returned to education, obtaining a first-class degree in philosophical studies from Oxford. It was during this period that Flew’s philosophical position became more refined. He enthusiastically studied and critiqued the standard arguments for God’s existence, including those of C.S. Lewis, whose society, the Socratic Club at Oxford, met to discuss such questions, and where Flew regularly debated Lewis and others. Flew went on to hold teaching positions at universities across the country, as well as a brief stint in Toronto, Canada, and gained a reputation as one of the most high-profile and engaging proponents of atheism in the U.K.

Flew wrote a number of books and articles on the philosophy of religion, many of which directly addressed and criticised theological justifications for God. God And Philosophy of 1966 won plaudits for how seamlessly it combined popular appeal and accessibility with academic detail and methodology. Continuing in this vein, it is Flew’s 1976 work The Presumption Of Atheism for which he is perhaps best known. Flew was dissatisfied with the popular application of the term ‘atheism’, asserting that while it was commonly used to express a positive claim, it should rather be flipped and understood as a negative expression – ‘in this interpretation an atheist becomes: not someone who positively asserts the non-existence of God; but someone who is simply not a theist.’ This distinction mattered for Flew as he believed the burden of proof for God’s existence lay entirely with the theist, and so one must therefore begin with ‘the presumption of atheism’. This understanding of the term ‘atheism’ has come to be more widely acknowledged through the work of contemporary atheist writers and is also indicative of Flew’s overarching dedication to the importance of evidence and open-mindedness in intellectual pursuits.

It was this commitment to going where the evidence leads that led Flew to make the shocking public revelation in 2004 that he was no longer an atheist but had instead adopted a deist position. According to Flew, recent scientific discoveries highlighting the incredible complexity of the natural world in remarkable detail now made the evidence for the existence of a divine being far more plausible than at any point in time previously. He still remained opposed to the idea of an afterlife, or to God being the ultimate moral arbiter, but he felt the needle had swung and that the evidence now pointed towards, at the very least, an unmoved mover, a first cause, akin to an Aristotelian conception of God. Flew’s announcement was met with scepticism and derision, with many believing that his advanced age and failing health were decisive factors in his conversion, and that this great but frail mind was being confused and exploited. Flew himself vehemently denied this to be the case and maintained to the end of his life that his shift from atheism was the result of nothing more than the logical pursuit of evidence to which he had devoted his entire academic life.

Whatever the reasons behind Flew’s switch, it is impossible to deny the impact he had on humanist ways of thinking, and the importance of his many years of work spent defending and articulating atheism as a viable philosophical position, rather than a taboo moral failing. He received numerous awards, including the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry’s ‘In Praise Of Reason’ award in 1985 for ‘long-standing contributions to the use of methods of critical inquiry, scientific evidence, and reason’. He was also a signatory of the Humanist Manifesto III in 2003, by which time his theological transformation was in full swing. An empiricist to the last, Flew’s move away from atheism demonstrates that while we may all reach different conclusions to one another on life’s grand questions, what unites us as humanists is our commitment to free enquiry and to improving the lives of our fellow humans for its own sake, rather than for the sake of any divine reward or punishment.

Love is a kind of courage, and, in the hearts of the man and woman who will here wed, there […]

Glasnevin Cemetery is a nondenominational cemetery in Ireland, first opened in 1832. The brainchild of Catholic rights leader Daniel O’Connell, […]

Ludovic Kennedy was a writer, journalist, and broadcaster, known for his investigations into miscarriages of justice. A human rights campaigner, he […]

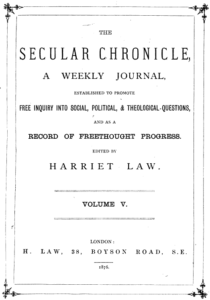

Harriet Law was a secularist and speaker, who also promoted women’s rights and socialist ideals. During the 1870s, Law’s house […]