Part of the reason for the recurring perception that atheism was a potential danger lay in the principles and structures of English Protestantism itself. Scripture characterised non-belief as a misguided inner feeling that betrayed both intellectual failure and moral deterioration. As Psalm 14 explained: ‘The fool hath said in his heart, There is no God. They are corrupt, they have done abominable works, there is none that doeth good.’ (Psalm 14:1, KJV).

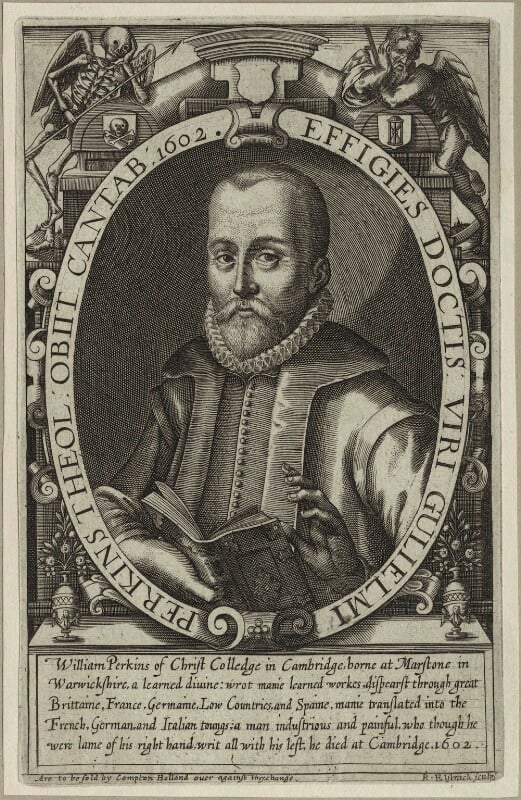

During the Elizabethan and Stuart eras, numerous Protestant theologians and ministers developed this idea in their writings and sermons. As French reformer John Calvin (1509-1564) had suggested in his Institutes of the Christian Religion (first translated into English in 1561): ‘So deeply rooted in our hearts is unbelief, so prone are we to it, that while all confess with the lips that God is faithful, no man ever believes it without an arduous struggle’. Developing English Calvinist ideas, the prominent Cambridge divine William Perkins (1558-1602) associated this affliction of the heart with satanic manipulation. Describing ‘The kingdome of darknes’ in a work on salvation published 1591, he argued that ‘members of this kingdome, and Subiectes to Satan, are his Angels, and vnbeleeuers, amongst whome, the principall members are Atheistes, who say in their hart, there is no God’. He went on to describe ‘Atheisme’ as a condition in which ‘the hart denyeth either God, or his attributes: as his Iustice, Wisdome prouidence, presence’.