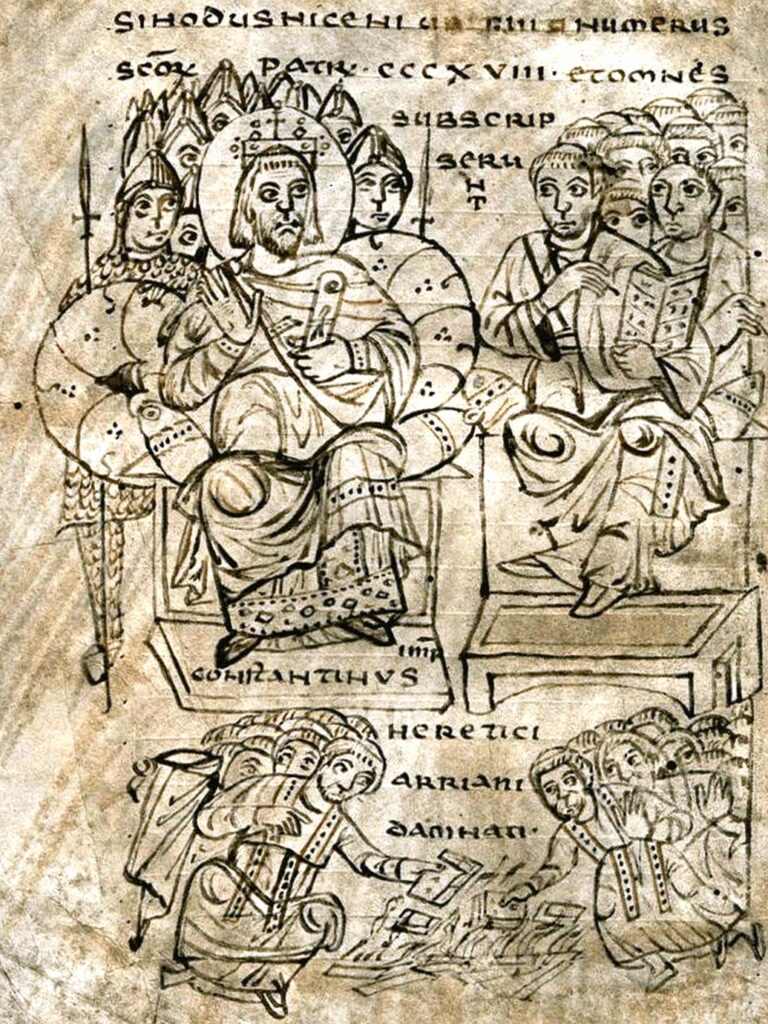

In spite of (perhaps because of) their unusual beliefs and their occasional persecution, Christians continued to win converts and their social influence continued to grow. In 313, when they could no longer be marginalised, they were granted freedom of religion by emperors Licinius (c. 263-325) and Constantine (c. 272-337). In 325 Constantine, who at some point became a Christian himself, convened a meeting of Christian leaders at Nicaea in present day Turkey to settle vexed theological disputes. They produced the systematised doctrine known as the Nicene Creed and in the decades that followed the policy of the imperial state was one of tolerance for Christianity alongside its traditional cults.

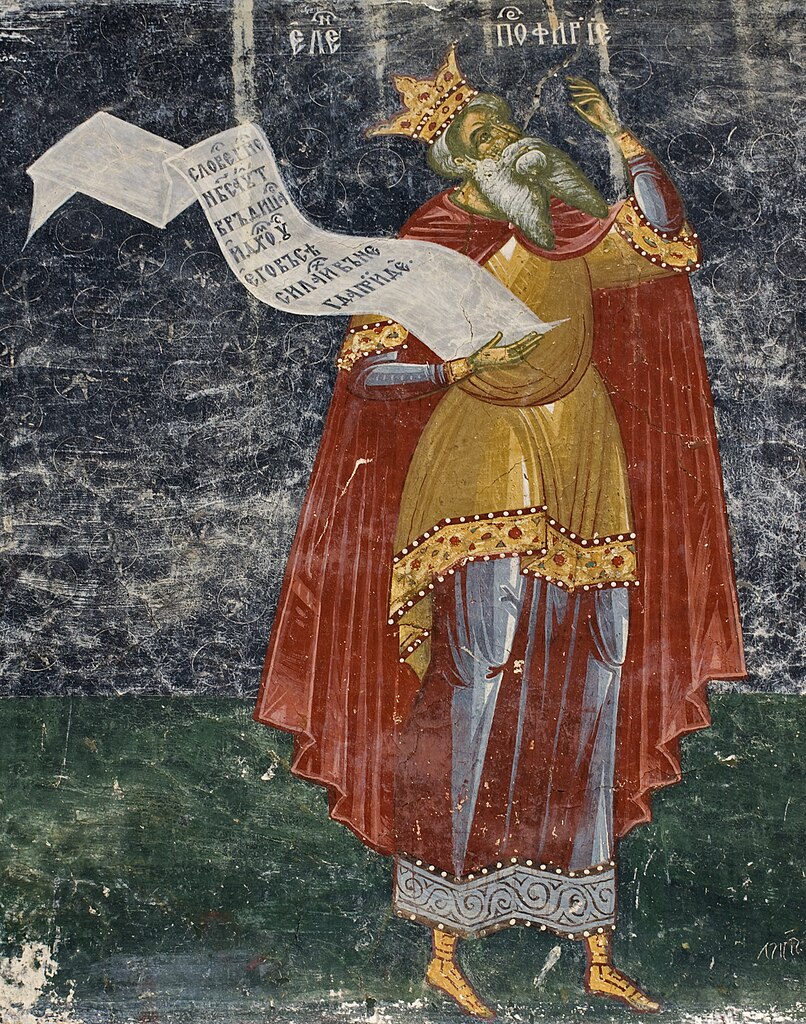

Then, in 380, Christians went from being tolerated to being dominant when emperor Theodosius (347-395) issued the Edict of Thessalonica, making it compulsory within Roman lands to be a Christian (specifically a Christian who accepted the Nicene Creed: all others were officially castigated as ‘heretics’). In under a century, Christianity had gone from being a minority sect to the state religion of a continental empire.