Auguste Comte was a French writer, philosopher, and social scientist, whose theory of positivism was a significant influence on the development of organised humanism. Comte’s ‘Religion of Humanity’, like humanism, removed supernatural sanction and motivation from ideas of human morality. Instead, it sought to place humanity and its achievements at the centre of social action, and introduced a kind of ‘secular worship’, found later in Stanton Coit’s ‘Ethical Church’. Though distinct and different from humanism, positivism’s three tenets (love, order, and progress) were influential on pioneering figures in the organised humanist movement, notably Frederick James Gould.

Auguste Comte was born on 19 January 1798 in Montpellier, France. He was a gifted student, and attended university in Paris. In 1824, he married Caroline Massin in a civil ceremony, and was later devotedly tended to by her following a breakdown in his mental health.

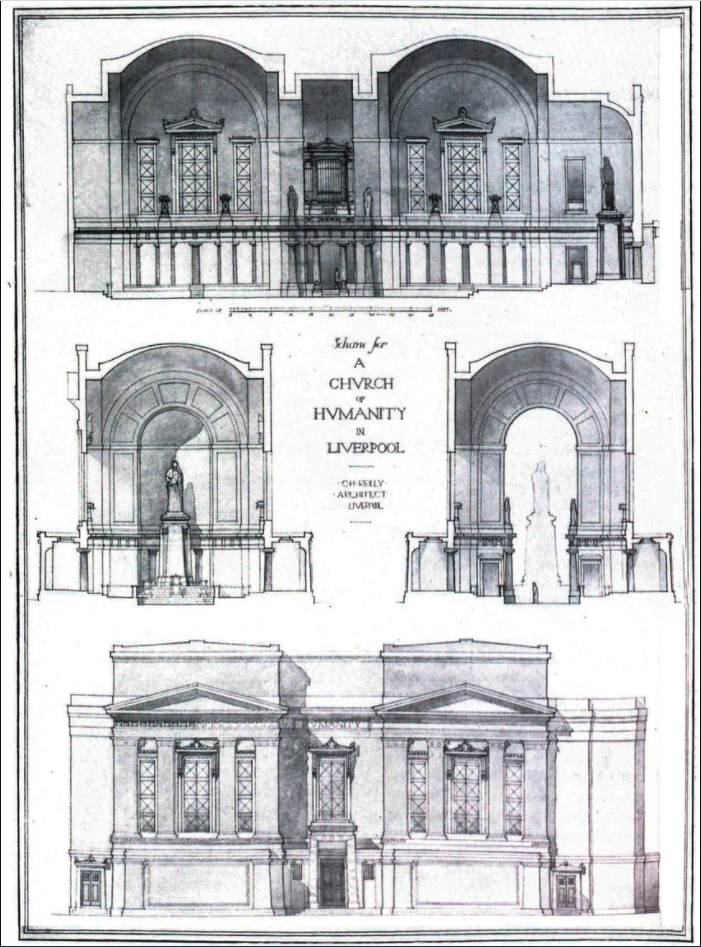

Comte’s most notable influence on the development of organised humanism in Britain, began with his his Course on Positive Philosophy, published in six volumes between 1830–1842, and later translated and condensed by freethinker Harriet Martineau as The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte in 1853. By the time of this publication in English, Comte had also founded the Positivist Society, and developed his ‘Religion of Humanity’, gaining adherents throughout the world.

Comte’s positivism has been considered a ‘humanist’ philosophy in so far as it placed moral agency with human beings, and dispensed with gods or any external, supernatural forces. However, Comte believed a philosophical elite was necessary to maintain order in a positivist society, and his ‘Church of Humanity’ became increasingly ritualised and autocratic. This led many who had once admired Comte’s idealist philosophies to criticise their physical implementation. Among these was John Stuart Mill, who saw positivist worship as ‘ludicrous’. Similarly, T. H. Huxley decried it as ‘Catholicism minus Christianity’:

I find therein little or nothing of any scientific value, and a great deal which is as thoroughly antagonistic to the very essence of science as anything in… Catholicism.

Despite criticisms like these, Comte’s philosophy was a noted influence on the humanist ideas expressed by other major thinkers, including John Stuart Mill and Rabindranath Tagore, who developed and humanised Comte’s Religion of Humanity. A prominent positivist in England was Frederic Harrison, who was a long time member of the West London Ethical Society, and celebrated the ‘ethical marriage’ of Stanton and Adela Coit in 1898 – a precursor of today’s humanist ceremonies.

Through the development of positivism, Comte coined a new term, ‘altruism’, to convey an ethic of godless selflessness (literally ‘living for others’). This was a distinctively humanist innovation which reframed morality as based in the relationships between human beings and in human societies, rather than, as in Christianity, the product of a moral order handed down to human beings from on high.

Comte died on 5 September 1857, and was buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery.

The ‘positive philosophy’ of Comte, and the translations of his works into English, were a significant influence on the thought and action of numerous positivists and humanists in the 19th century and beyond. Freethinking writer Harriet Martineau translated Comte’s writings into English; long time ethical society member Frederic Harrison ‘preached’ positivist philosophy; pioneering humanist educationist Frederick James Gould was deeply influenced by Comtean ideas; and foundational figure of the modern welfare state William Beveridge was raised in a home steeped in positivist philosophy. He was also a profound influence on the novels, essays, and poems of George Eliot. In removing the need for gods from ideas of goodness and morality, Comte helped to lay the foundations for the organised humanism of today, and introduced ideas which helped to guide those who pioneered and developed the humanist movement.

If the basic cause of an unsuccessful marriage is removable, conciliation is the proper procedure. If it is not removable, […]

The object of this Society is: To increase the knowledge, the love, and the practice of the right. Its bond […]

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]

Dr Alice Vickery was a humanist, physician, and devoted champion of women’s reproductive rights. Her tombstone inscription remembers her as […]