Bill Bynner was a humanist, socialist, and civil servant. As the editor of South Place Ethical Society‘s Ethical Record wrote in 1984, his example provides ‘a vignette of a humanist life’: a compassionate and practical humanism, manifested in his daily life as well as in his wider efforts for peace and social welfare. Bynner was closely involved with the Humanist Housing Association, as well as with the Socialist Secular Association (founded in 1981 ‘to unite ethical, humanist, secularist, rationalist and freethinking socialists’).

The below is reproduced from the Ethical Record, April 1984.

(His daughter, Sheila, sends us the following from the ceremony conducted by Arthur Atkins at Putney Vale Cemetery for Bill’s funeral, with some 20 people present. The text she sent is given in full because it not only tells a brief story of Bill’s life, but is a vignette of a humanist life: with its involvement in the day to day at the levels of family, country, world and concerns—Editor.)

William Bynner was born in Birmingham in 1900 into a poor working class family. He used to say he was a Victorian, having been born at the very end of Queen Victoria’s reign. His father was a cabinet maker/joiner who died when Bill was 13. He left school soon after his father died and his first permanent job was as a Boy Clerk in the Post Office. For most of his working life he was a civil servant (with interruptions for two World Wars). He was very fit and active and at the age of 17 cycled from Birmingham to London (he said the last 30 miles were quite easy—downhill all the way!). He was called up in 1918 and fortunately was a fortnight too young to go into the trenches. He used to say Prime Minister Lloyd George saved his life because he held back the batch of young conscripts to which Bill belonged.

In the years between the wars he married and brought up a family in Mitcham. He played cricket, rugby, football and in the 1930s mainly tennis. He worked on the outdoor staff of the Ministry of Health, inspecting insurance stamps (which in those days employers had by law to stick on their employee’s cards). This was a tough job in the East End of London. He joined the Territorial Army in 1938 after Munich and in September 1939 he was called back to camp from a summer holiday on the south coast (where he was with his wife and three daughters). During the blitz he manned the guns in an anti-aircraft unit on gun sites all round the perimeter of London. He was demobilized in 1944, when the health of his dear wife Nan became increasingly poor. She died in 1950.

He retired from the Civil Service in 1960 and for the last 20 years of his life (perhaps as a reaction to the demand for political and social conformity in those days) he came increasingly to take an anti-establishment line in religion and politics.

He joined CND [Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament], taking part in the Aldermaston marches of the 1960s. He became a Humanist and a member of the National Secular Society and helped to start the Socialist Secular Association. During these years he wrote a novel and some poetry. Another of his interests was the Humanist Housing Association, where he worked as a volunteer with Lindsay Burnet buying up large old houses which were then refurbished and split up into flats for needy tenants. He took pride in helping to establish this Association.

He himself lived in Blackham House in Wimbledon for some years before going to live with his daughter. He remained fit and active until his mid-70s. In the last four years of his life, although increasingly frail, he never complained or felt sorry for himself. He was honest, fiercely independent, anti-establishment, socialist and anti-religion. In spite of this his oldest friend, whom he knew since 1922 was Clerk of the Parish Council in Panham (where he lived for a few years). He was unfailingly generous to his family and friends and the causes he supported, but could be witheringly sarcastic about aspects of life or government he disliked.

He valued the friendship of so many people in the humanist and secular movement, while at the same time he kept the friendships of his earlier years and reconciled them all because he valued people. He will be greatly missed.

Without denying or affirming a life after death, or reality beyond experience… we can (without injury to our moral life) […]

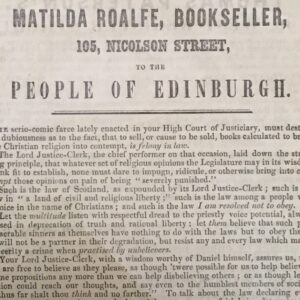

I will never voluntarily obey any law which is an outrage on human reason. Matilda Roalfe Matilda Roalfe was an […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. […]