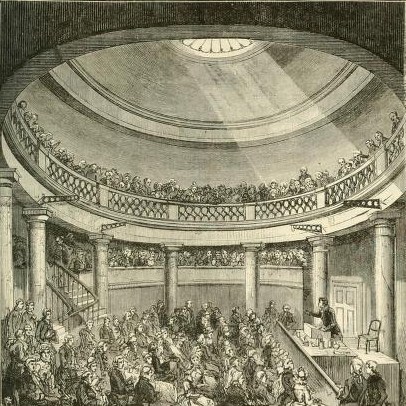

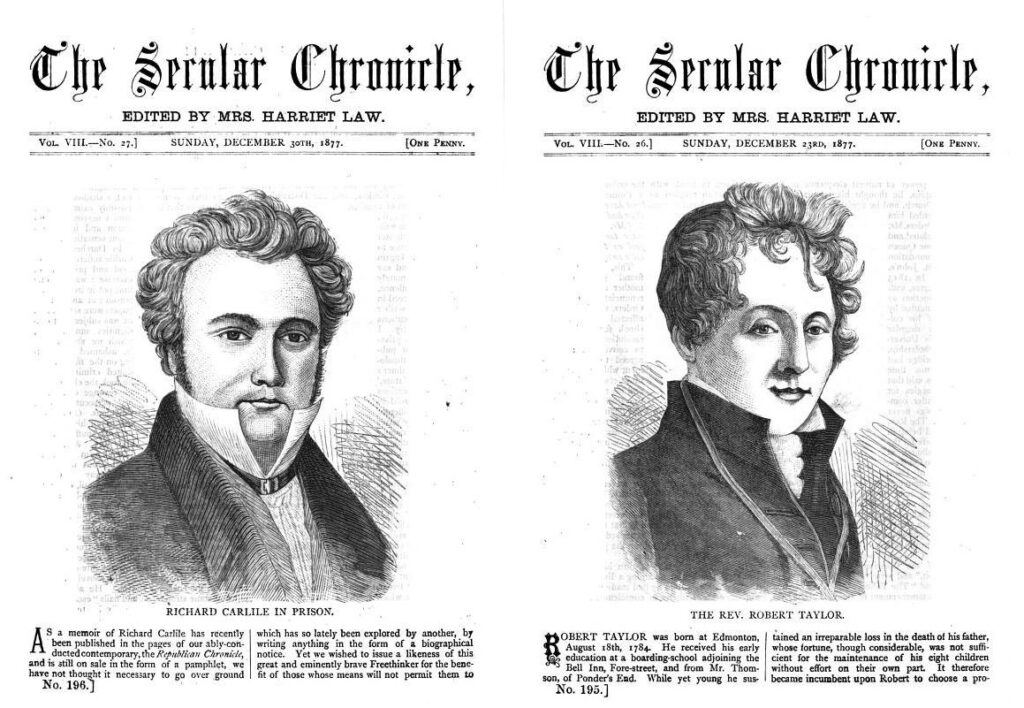

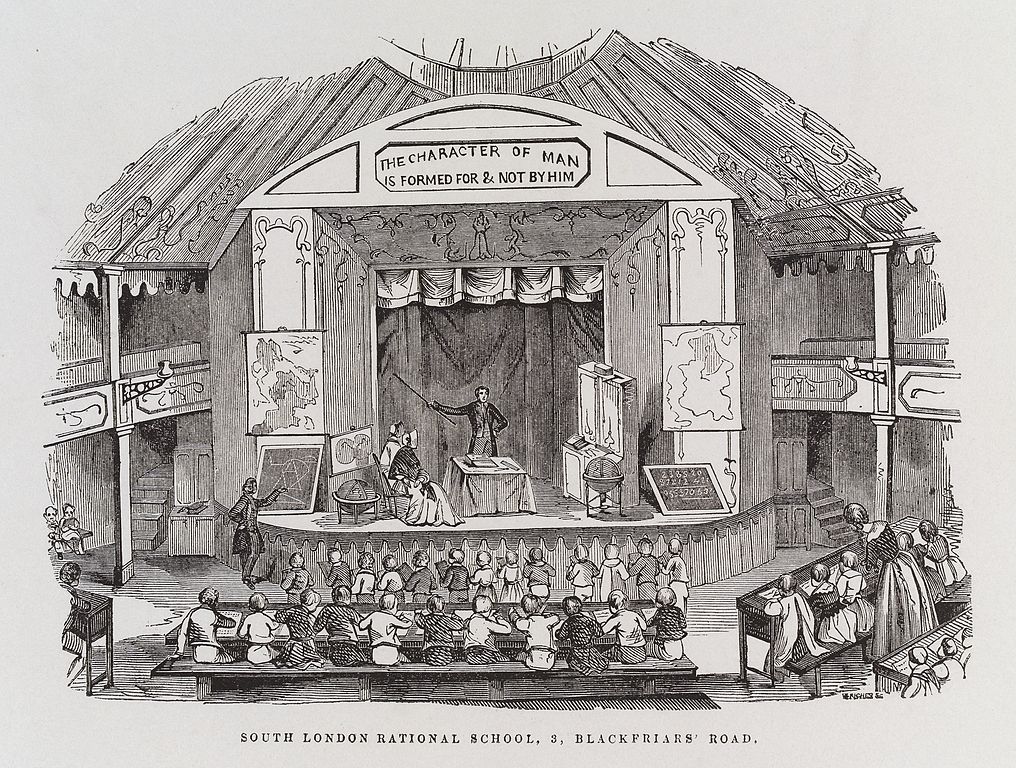

From its origins in 1787, the Blackfriars Rotunda was associated with learning and the widening of access to knowledge. First built to house the natural history collection of Sir Ashton Lever, it was later home to the Surrey Institution, hosting lectures on scientific and literary subjects. Later still, under the tenancy of Richard Carlile and the so-called ‘Rotunda Radicals’ between 1830-1832, it became a site of radical politics and outspoken freethought, with speakers including Robert Taylor (‘the Devil’s Chaplain’, imprisoned in 1831 for blasphemous libel) and Eliza Sharples (‘the pythoness of the temple’, a lecturer on freethought and women’s rights). No longer in existence, the building sat on the southern side of Blackfriars Bridge, at 3 Blackfriars Road.

Displaying objects from across the world even before its association with radical politics, the Rotunda in its early days had been a promoter of education being made available to wider society and encouraging greater engagement with the sciences. In particular, the collection at the Rotunda had been part of a wider initiative of object collections moving beyond aristocratic settings and being made available to the middle classes.

Following the dissolution of the Leverian collection, the Rotunda had become home to The Surrey Institution, an establishment celebrating the arts, scientific research, and literature. From offering lectures on literature by Samuel Taylor Coleridge – a prominent figure in the Romantic period – to composers such as Samuel Wesley, the Rotunda encouraged appreciation for arts and culture moving beyond that of scientific discovery, highlighting the importance of self-education.

In the absence of a better—the palladium of what liberty we have… the birthplace of mind, and the focus of virtuous public excitement.

Richard Carlile speaking in 1831 of his ambitions for the Rotunda, placing emphasis on liberty and freedom of speech.

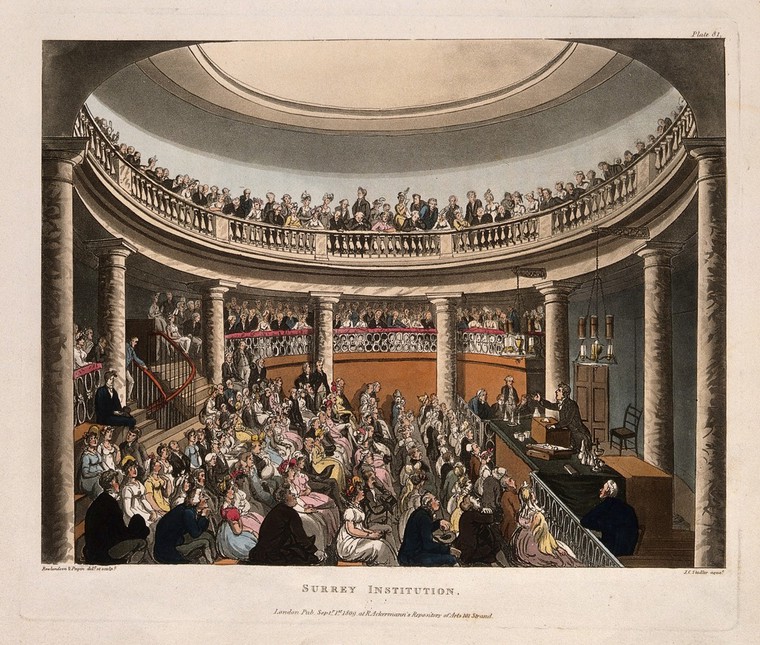

Following the end of The Surrey Institution at the Rotunda, radical publisher Richard Carlile set out in his campaign for the newly refurbished Rotunda to be at the forefront of radical politics in 19th century England. Carlile, already infamous for advocating freedom of the press and a rational approach to birth control, leased the Rotunda in 1830. Tricolour flags decorated its facade and interior, symbols of liberty drawing inspiration from the 1830 French Revolution. The situation in England was similarly volatile. Social discontent sparked political movements seeking to reform the electoral system, with working class movements gaining strength. The Rotunda became a hotspot for heated and radical discussions, including attacks on religious superstition and calls for radical reform, quickly becoming known as a threat to the authorities.

On the 8th of November 1830, a large crowd who had assembled by the Rotunda marched in opposition to the police force at the time and expressed dissatisfaction with Home Secretary Robert Peel. They were later met by police resistance, preventing them from storming the House of Commons. Authorities clearly held strong views against them, with various periodicals recording the event as a turning point within the radical movement. A piece for the Berkshire Chronicle dated 27 November 1830 clearly wrote in favour of police involvement, praising their efforts to suppress the rioting of so-called ‘thieves and vagabonds.’

The Rotunda provided a place for the working class to join forces as a community in discussing approaches to better the political system for fairer representation, also becoming home to the headquarters

of the National Union of the Working Classes (NUWC) between 1831-2. Carlile ensured lectures at the Rotunda were accessible to the working class by keeping admission prices affordable, and adhered to his ideals of free discussion by hosting speakers whose views differed from his own.

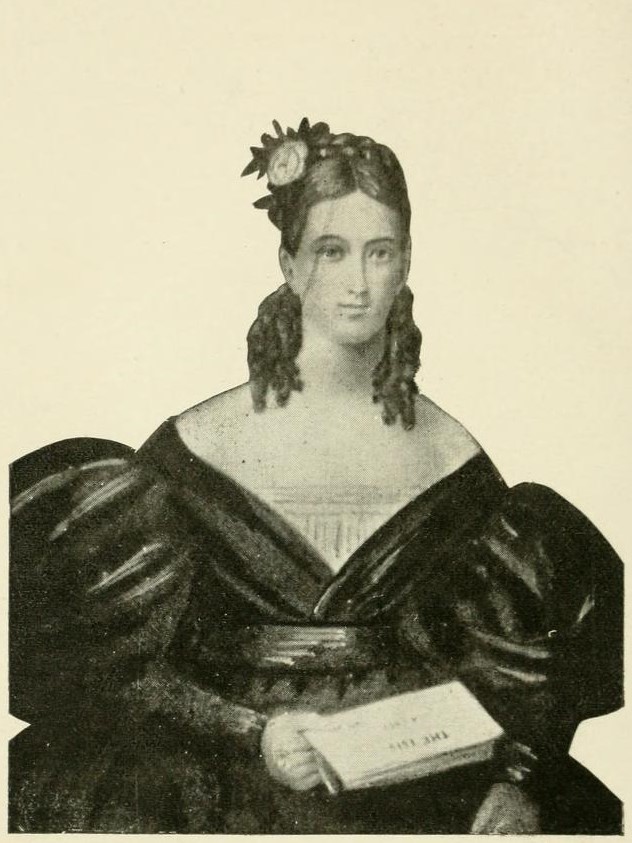

Carlile himself was imprisoned in 1831 on charges of seditious libel. Although his partner (and lecturer at the Rotunda) Eliza Sharples attempted to keep it in operation, facing mounting debts the lease of the Rotunda was relinquished the following year.

In the period following the end of Carlile’s lease in 1832, the Rotunda continued as a site of education, and staged various concerts and theatrical performances. In 1843, on his release from Gloucester Gaol, George Jacob Holyoake took up a teaching post there, and later attempted to raise a subscription for it to be taken over by socialist, feminist, and freethinker Emma Martin. His efforts were thwarted by the landlord’s refusal to let the building for ‘atheistical purposes’. As Christina Parolin has pointed out:

The power of the landlord to exclude Martin and other rationalist groups… points to the inextricable link between political power and property in the early nineteenth century and the continuing struggle for access to sites of assembly. It further highlights the significance of Carlile’s success during 1830–32 in providing the radical movement with a unique space of their own.

Being subject to damage during the Second World War, the Rotunda was officially destroyed in 1958.

As we can see, though the Rotunda’s uses and associations changed considerably over time – from staging popular scientific collections, to promoting arts and culture, acting as a hub of radical activity, and a home of music and education – it consistently stood for the promotion of free speech, and opportunities for self-development through education, culture, and free expression; ideals still carried forward by humanists today.

Christina Parolin, Radical Spaces: Venues of popular politics in London, 1790-c. 1845 (2010)

Philip Lockley, ‘The Political Messiah’ in Visionary Religion and Radicalism in Early Industrial England: From Southcott to Socialism (2012)

Edward Royle, Victorian Infidels: the Origins of the British Secularist Movement, 1791-1866 (1974)

By Mannya Sajith

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]

Humanism is a philosophy – one which gives us a coherent stance for living. We believe the humanist approach to […]

There is no one who will deny the value and importance of truth, but how is it to be ascertained, […]

Ernestine Mills, an enamelist, and her husband Dr. Herbert Henry Mills were both active members of the Ethical movement, and […]