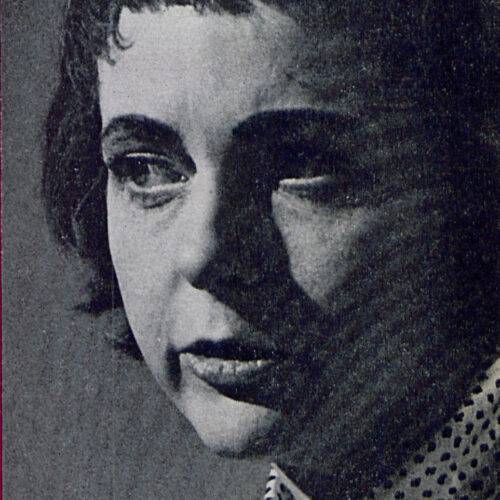

We are (of all the synonyms I most prefer to ‘humanist’) freethinkers. We are deprived of nothing. We have lost nothing… We are liberated into and given the freedom of the whole kingdom of the imagination…

Brigid Brophy, ‘Faith Lost – Imagination Enriched’ in The Humanist Outlook (1968)

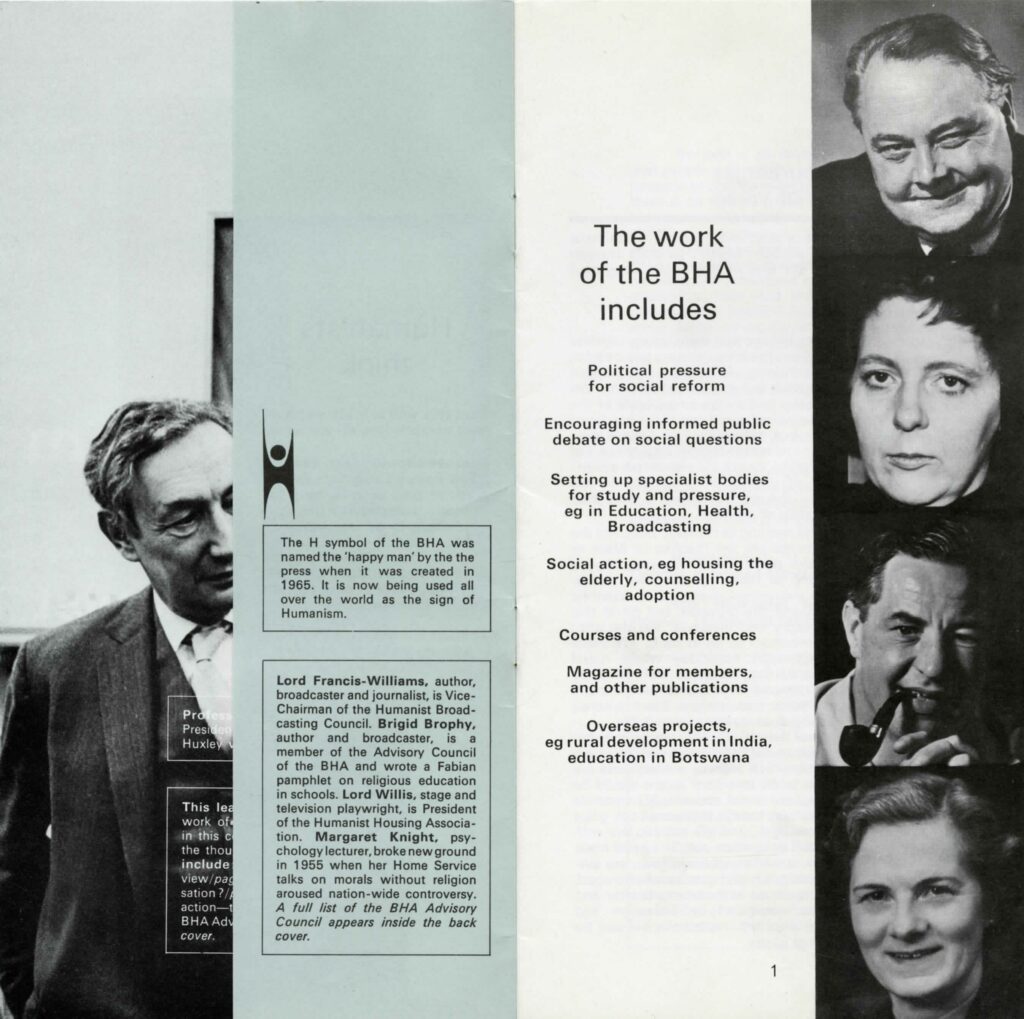

Brigid Brophy was a writer, humanist, vegan, and activist. A prominent voice for the rights of all sentient creatures, she was also a member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) from 1965, and an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association from 1984. As a leading figure in the Writers’ Action Group, Brophy successfully campaigned for authors’ rights, helping to bring about the Public Lending Right in 1979. Brophy embodied the argument that an embrace of rationalism need not mean the sacrifice of imagination, leaving a rich legacy of inventive prose and articulate humanism to prove it.

Brigid Antonia Brophy was born in London, the only child of John and Charis Brophy, a novelist and teacher respectively. A gifted and precocious child, she began writing from an early age, later crediting her father’s encouragement – and the writings of George Bernard Shaw and Evelyn Waugh – for her own gifts as a writer. She went up to St. Hugh’s College, Oxford on a scholarship in 1947. There, in Brophy’s own words, she:

… acted in the belief that I had more to learn by pursuing my personal life than from textual emendation, with the result that the authorities could put up with me for only just over a year: I came down at the age of 19 without a degree and with a consequent sense of nudity which I have never quite overcome.

Initially earning her living as a shorthand typist, Brophy soon embarked on her career as a writer. Her first book, published in 1953, was a short story collection, The Crown Princess. Her second, Hackenfeller’s Ape, appeared in the same year, taking animal liberation as its theme and turning Brophy into a vegetarian. Over the course of her life, Brophy’s pen ranged over works of fiction, non-fiction, criticism, and biography. Fellow author Peter Parker has called her ‘determinedly experimental as a writer’, whose works nevertheless ‘constitute a highly coherent and distinctive oeuvre’.

In addition to (and often within) her writing, Brophy was an eloquent and active humanist. In a letter to the New Humanist on its 100th birthday in 1985, she wrote:

Freethinkers seldom win fame, fortune or establishment honours by their level-headed insistence on rational criteria of evidence but they are doing the only thing that can keep human civilisation going.

Brophy herself was, as the Times would later note, ‘devoted… wholeheartedly to the role of public crusader’, not only in the name of freethought, but for the rights of all sentient beings. She was an outspoken anti-vivisectionist and campaigner against blood sports, an articulate critic of faith schools and compulsory collective worship, and a vocal advocate of LGBT rights. She was also a driving force in the campaign for writers to be paid when their works are borrowed from public libraries, which resulted in the Public Lending Right Act 1979. This formed part of Brophy’s fervent belief in the value of art and literature to life and living. As she argued in Prancing Novelist (1973):

The most reasonable and practical defence that can be put forward for fiction is to demand justice: in the shape of dinners for its practitioners. If fiction is (temporarily) dead, that is because it has been starved.

In 1983, Brophy was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, which eventually confined her to a wheelchair. Even in the face of her own progressive debilitation, she remained forthright in her opposition to animal testing, and continued to write. Her collection of essays and journalism, Baroque-‘n’-Roll (1987), included a characteristically lucid and humane account of her illness. She wrote:

The chief curse of the illness is that I must ask constant service of the people I love most closely. Sporadically it is, in its manifestations, a disgusting disease. Also sporadically, it has another antisocial result, wrapping one suddenly in an inexorable fatigue like a magic cloak of invisibility. Its sporadicness destroys the empiricism by which normal people proceed without noticing they are doing so… It is an illness that inflicts awareness of loss. The knowledge that I shall never be in Italy again is sometimes a heaviness about me like an unbearable medallion that bends my neck. Yet the past is, except through memory and imagination, irrecoverable in any case, whether or not your legs are strong enough to sprint after it. All that has happened to me is that I have in part died in advance of the total event.

Brophy had been married to art historian Michael Levey since 1954. Although they both ultimately regarded the institution of marriage as immoral, theirs was a warm, supportive, and unconventional partnership, which Brophy described as ‘a matter of serene happiness’. They had one daughter, Kate. Levey stepped down from his role as Director of the National Gallery to care for Brigid, and the couple moved from London to Lincolnshire in 1991. Brigid Brophy died on 7 August 1995, and was cremated.

She has always the gift of a most stirring sort of firmness. It is not the tone of a know-all, it is not remotely bossy; it is, I suppose, basically, the sound that logic makes.

Edward Blishen on Brigid Brophy, 1989

Brophy’s significant legacy as a writer, an activist, and a humanist, was perhaps best summed up by Nicolas Walter, who wrote in 1995:

Brigid Brophy was more than ‘an opponent of religion’. She was a committed and valued member of the freethought movement for more than 30 years, an active speaker and writer for the British Humanist Association and the National Secular Society, a helpful supporter of the Committee against Blasphemy Law and an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, the author of eloquent pamphlets and articles on religious education and sexual education, marriage and censorship, and a good friend.

Nicolas Walter, The Guardian, 16 August 1995, quoted in the New Humanist

The Humanitarian League is a Society of thinkers and workers, irrespective of class or creed, who have united for the […]

Not Religion as a Duty, but Duty as a Religion. Felix Adler(A motto of the East London Ethical Society) The […]

Elhanan Winchester was the first minister of the dissenting congregation that eventually became the humanist South Place Ethical Society in […]

My chosen ground Inscription on the John Hewitt Cairn John Harold Hewitt (1907-1987) was the most significant Ulster poet to […]