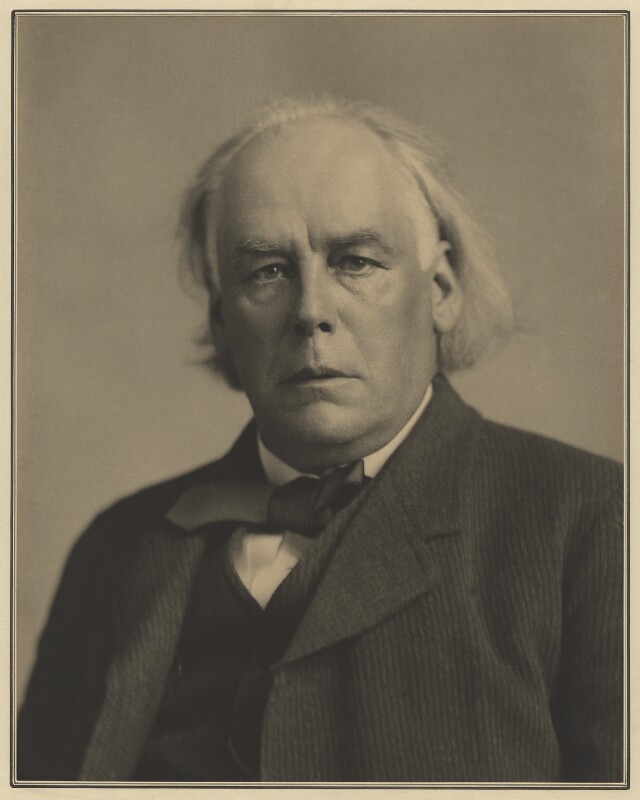

Charles Bradlaugh was a leading freethinker, secularist, and founder of the National Secular Society. His efforts to take his seat in Parliament as elected MP for Northampton led to a protracted campaign for solemn affirmation, rather than oath swearing, and his publication with Annie Besant of birth control literature made a stand against obscenity laws. A fierce defender of freedom of speech, and tireless champion of rationalism and reason, Bradlaugh took up many of the causes central to the efforts of Humanists UK today.

Charles Bradlaugh was born in Hoxton, East London on 26 September 1833, the eldest of six children. Today his birthplace is marked by a London Borough of Hackney brown plaque.

Bradlaugh’s origins were humble, his father (also Charles) being a solicitor’s clerk. He was always to think of himself as being of the poor and speaking on their behalf. His upbringing was orthodox and as a youngster he attended Saint Peter’s Church, Hackney Road. He was soon identified as one of the brightest pupils and appointed as a Sunday School teacher by the Reverend John Graham Packer.

As part of his studies the young Bradlaugh examined the four gospels carefully and was troubled by what seemed to him to be inconsistencies. Consequently, he wrote to Packer for advice and explanation and met with an unexpected and unfriendly response. Packer condemned Bradlaugh to his parents and removed him from his post as a Sunday School teacher. Matters developed rapidly after this with Bradlaugh renouncing his religious beliefs. The Reverend Packer persuaded Charles Senior to give his son three days to change his mind. Bradlaugh did not hesitate or compromise and at the age of 16 left home and briefly took up lodgings with Eliza Sharples, the former mistress and co-worker of Richard Carlile. As such he had philosophically and physically joined the ranks of radical freethought.

In the years that followed he began to write and lecture, although he struggled to make a living, eventually enlisting in the army for the bounty. He was sent to Ireland where the misery he saw made a lasting impact. However, army life did not suit him and he was bought out, returning to London and the editorship of freethought newspapers, eventually assuming control of the National Reformer which was to be his mouthpiece for the rest of his life. By now Bradlaugh was well-known as a popular, radical, republican, and freethought speaker, attracting large crowds wherever he spoke.

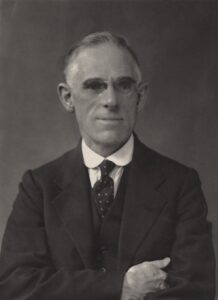

Many years later Harry Snell described his impressions of Bradlaugh. Snell was a Labour MP and later, as Lord Snell, led the Labour Party in the Lords:

Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man fascinated me… and I became one of his humblest but most devoted of his followers.

Tom Mann was a young trade unionist when he first heard Bradlaugh speak:

When championing an unpopular cause, it is of advantage to have a powerful physique. Bradlaugh had this; he had also the courage equal to any requirement, a command of language and power of denunciation superior to any other man of his time… He was a thorough-going Republican. Of course, in theological affairs, he was the iconoclast, the breaker of images.

Prior to 1866 radical and freethought leadership was fragmented and, in Bradlaugh’s opinion, insufficiently positive. On 15 July 1866, The National Reformer announced plans ‘to place the Secularists of Great Britain who, during the past few years have enormously increased in numerical strength, in more intimate communication with each other’. Bradlaugh’s objectives were always political and were initially closely related to the radicals’ attempts to broaden the franchise.

On 9 September Bradlaugh used the columns of his newspaper to proclaim the programme and principles of a new National Secular Society, with him as temporary President pending a national conference. This eventually occurred in Bradford in November 1867 when Bradlaugh’s presidency was confirmed. Bradlaugh now had the backing of a network of loyalists and a national organisation to support him in the great struggles that were to follow. He also had the benefit of a headquarters at the spacious Hall of Science on Old Street.

Inevitably Bradlaugh’s rise brought him into conflict with George Jacob Holyoake and this was to fester for the rest of his life. However, it was Bradlaugh who had the popular following. His outspoken militancy, resolve, and courage appealed to his working class following and his ability as a platform speaker and organiser to some extent eclipsed Holyoake’s more understated, reflective style, and tendency to compromise with opponents.

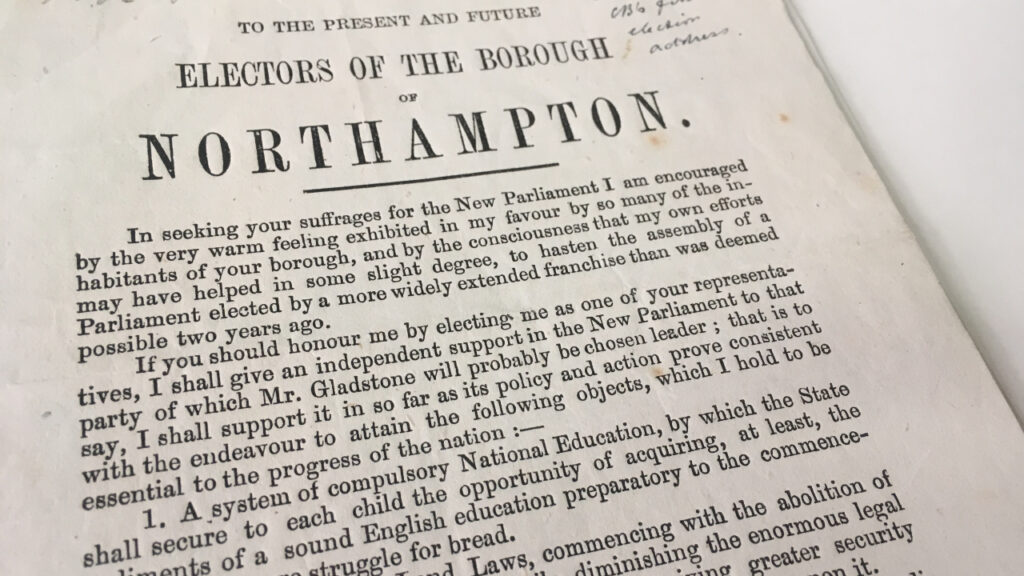

By 1877 Bradlaugh was already well-known and, to some extent, notorious in the eyes of the establishment. However in that year he was thrust into the limelight in 1877 when he and Annie Besant republished a birth control pamphlet, Charles Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy. This extraordinary case was to have further consequences for Bradlaugh when in 1880 he was elected to the House of Commons as an MP for Northampton. As an atheist and a republican, Bradlaugh sought the right to affirm, rather than swear an oath of allegiance to God and the Queen. He was refused, and was unable to take his seat until 1886.

Bradlaugh was a hard-working MP, particularly noted for championing native rights in India. In 1889, he attended the Indian National Congress in Bombay. By this time, though, he was becoming increasingly ill.

Perhaps Charles Bradlaugh’s greatest recognition occurred as he lay on his deathbed. On 27 January 1891 the House of Commons resolved that its original decision preventing him from taking the oath ‘be expunged from the journals of the House, as being subversive of the rights of the whole body of electors of this Kingdom’.

Charles Bradlaugh died from kidney disease on 30 January 1891 aged 57 without knowing of the resolution. Among the mourners at his funeral was a young Mohandas Gandhi. Today, Bradlaugh’s achievements are commemorated by his statue in Abingdon Square, Northampton and by his grave in Brookwood Cemetery. Perhaps most poignantly, in 2016 Suzie Zamit’s portrait bust was unveiled in the Palace of Westminster. Today it is displayed alongside other celebrated reformers and radicals. Charles Bradlaugh’s heroism and self-sacrifice is not forgotten and his example remains an inspiration to humanists today.

By Robert Forder

In the first place, then, why do we botanise?… The enjoyment of the beauty and fascination of flowers in their natural […]

Harry Snell was a socialist politician and campaigner, a devoted advocate of the Ethical Movement and a key figure in […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

Because no one will believe without a splash from a fontTheir baby will howl in eternal cold, or fire,And no […]