By 1880 Charles Bradlaugh had emerged as the undisputed leader of the secularist cause and the leading radical of his time. He was famous for his oratory and could attract audiences of thousands. His books and pamphlets on a variety of radical themes commanded huge sales and he was known nationally for his campaign to publish Charles Knowlton’s birth control pamphlet, The Fruits of Philosophy.

As a constitutionalist Bradlaugh was convinced that the way to change society was through Parliament. In 1868 he first stood for election for Northampton which was then a single constituency electing two MPs. He chose Northampton, a town of shoemakers, for the radical traditions associated with that trade. In 1880 Bradlaugh was adopted as a Liberal candidate alongside Henry Labouchere. The timing was fortunate. In 1880 the Liberals achieved their biggest general election victory of all time and William Gladstone formed his second ministry. Bradlaugh and Henry Labouchere were returned as Northampton’s MPs.

Since 1870 non-believers had had the legal right to make a secular affirmation in the English and Welsh courts. Bradlaugh believed this qualified him to affirm when taking his seat in the House of Commons and informed the Speaker of his intention. As an atheist and republican he preferred not to take an oath of allegiance to God and the Queen, although he would do so if it meant he could take his seat, the words of the oath being meaningless to him.

The House of Commons refused to allow his affirmation, so Bradlaugh applied to take the oath but was again refused. He was effectively barred from taking his hard-won seat. To Bradlaugh and many others this was a grievous breach of democratic rights. He was being refused his seat because of what others thought of his opinions, despite the wishes of his constituents.

In the years that followed he continued his fight to take the oath. Four times in the early 1880s his constituents re-elected him; four times he made passionate speeches at the Bar of the House. The Bar marked the boundary of the House – he was allowed to speak from there, because he was not strictly within the Chamber. On one occasion he concluded his speech with these words

I have no fear. If I am not fit for my constituents they shall dismiss me, but you never shall. The grave alone shall make me yield.

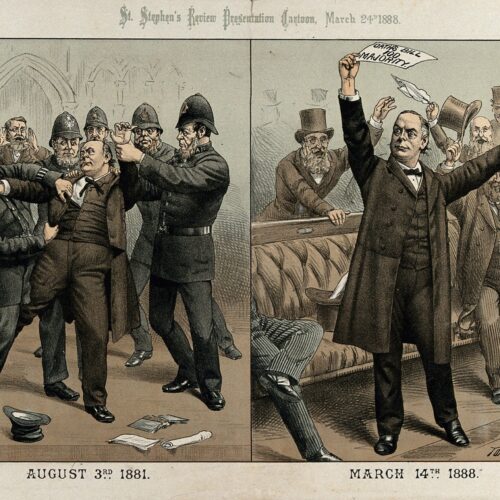

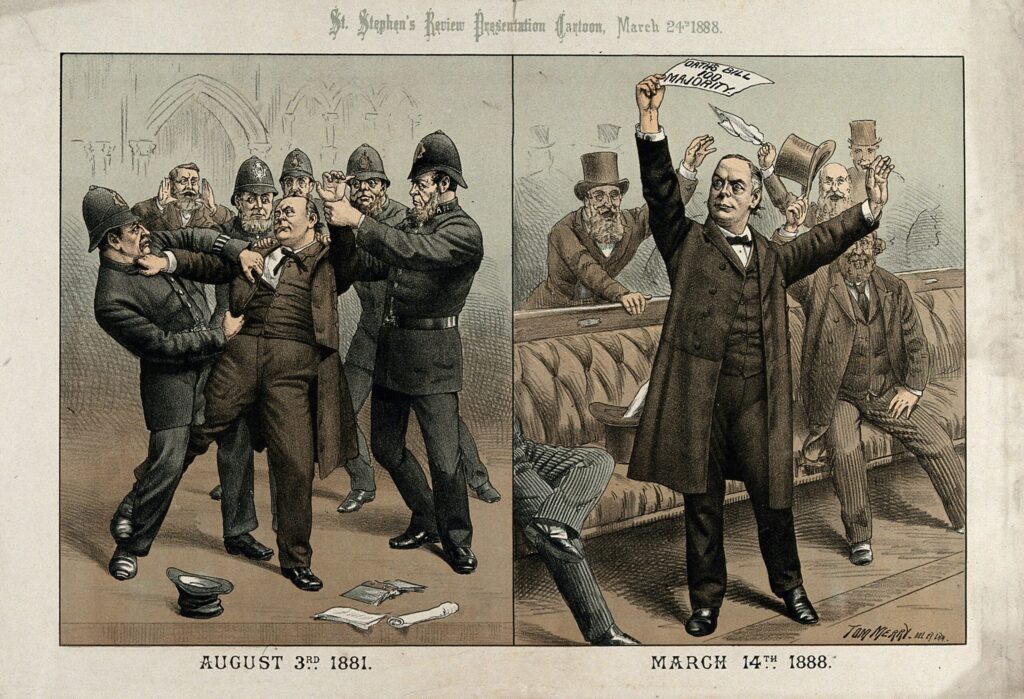

On one occasion he refused to withdraw when commanded to do so, was taken into custody, and confined to the prison room of the Clock Tower before being released the next day. On another, Bradlaugh came to the House of Commons at the head of a vast crowd demanding that he be allowed to take his rightful place. He was physically ejected by the police and parliamentary officials suffering injuries in the process. Despite this provocation he successfully urged the crowd to disperse peacefully.

Bryan Niblett, who has written a recent biography of Bradlaugh describes the scene:

Bradlaugh, advancing purposely to the Chamber door where Erskine (the Deputy Serjeant-at-Arms) stood in his way, spoke in a commanding voice: ”I am here in accordance with the orders of my constituents, the electors of Northampton; any person who lays hands on me will do so at his peril”. Erskine replied that he had orders not to admit Bradlaugh. “Those orders are illegal”, declared Bradlaugh, whereupon he stepped forward brushing Erskine aside. This was a signal for the messengers to act, and act forcibly. They grabbed Bradlaugh by his coat, his throat and by his arms. Bradlaugh fought back, grasping one messenger by his collar and refusing to let go. He stood like an oak rooted to the floor of the Lobby. These ten, tugging Bradlaugh mainly by the arms, slowly dragged him from the Lobby, down the passage, and threw him in the Palace Yard.

Eventually the impasse was resolved after the General Election of 1885 when a new Speaker took the dramatic decision to allow Bradlaugh to take the oath, which he did on 13 January 1886. Almost six years after being first elected Bradlaugh had won, but at immense personal financial and physical cost .

His victory was further underlined by Parliament passing an Oaths Act (1888) which extended the civil rights of unbelievers by endorsing their right to affirm when taking their seat in Parliament. Many MPs take advantage of this today. In the years that remained to him, Bradlaugh championed much reformist legislation and received the accolade of becoming known as ‘The Member for India’ for championing Indian people’s interests.

The Rationalist Press Association (later known as simply the Rationalist Association) had its origins in the London print works of […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) began as the Birmingham Pregnancy Advisory Service, created to provide access to safe, legal, […]

…having now exceeded the age of three score years and ten, I would say that up to the present I […]