… in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to realise our emotional aspirations…

Charles Kennedy Scott, Letter to members of the Ethical Church, 1915

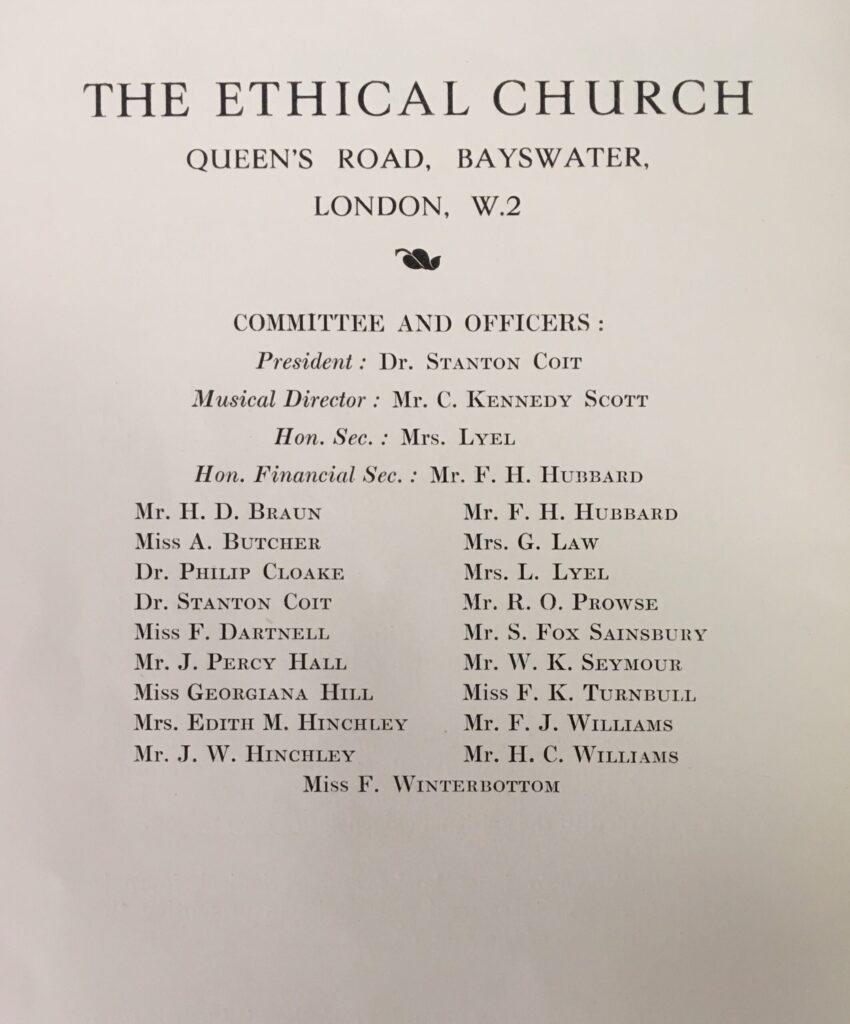

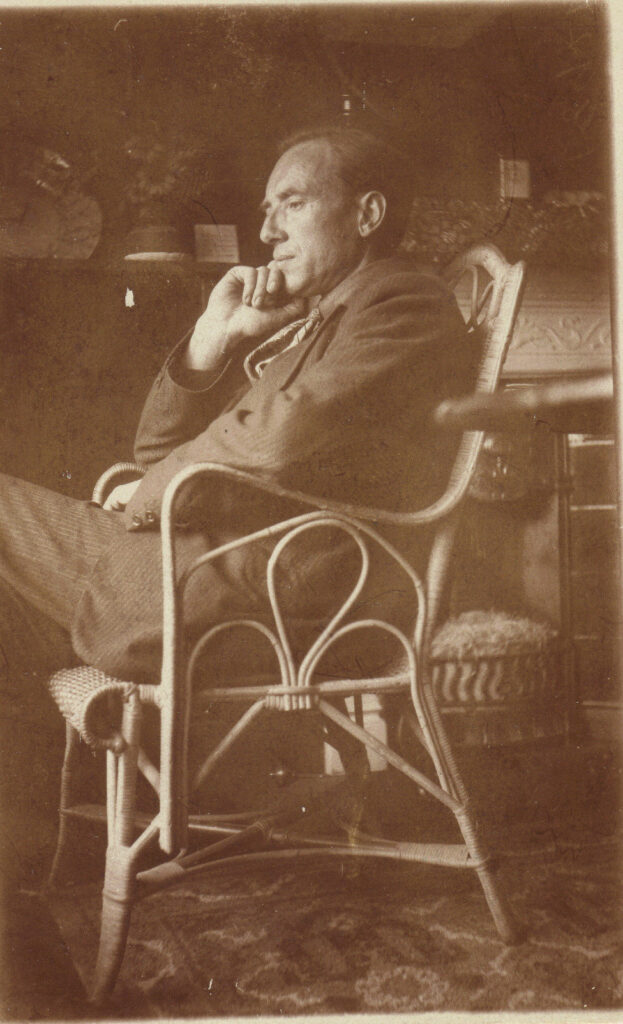

Charles Kennedy Scott was the musical director, and longtime member, of Stanton Coit‘s Ethical Church, remaining closely connected with both for much of his life. Keenly aware of the power of music as a celebration of history and humanity, Scott also founded the Oriana Madrigal Society, the London Philharmonic Choir, and the Bach Cantata Club. Scott ended his days in the same building which housed the Union of Ethical Societies’ offices (now Humanists UK), having spent his life an active humanist and passionate advocate of music and culture.

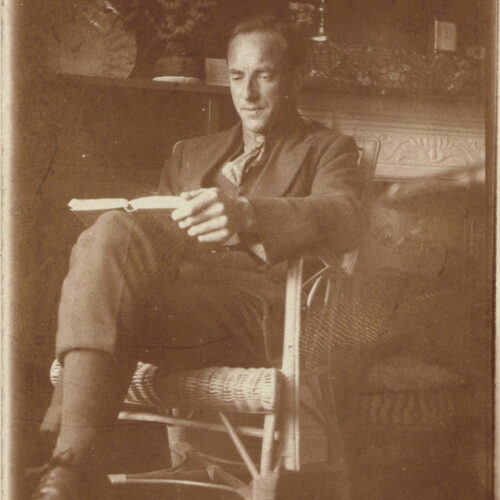

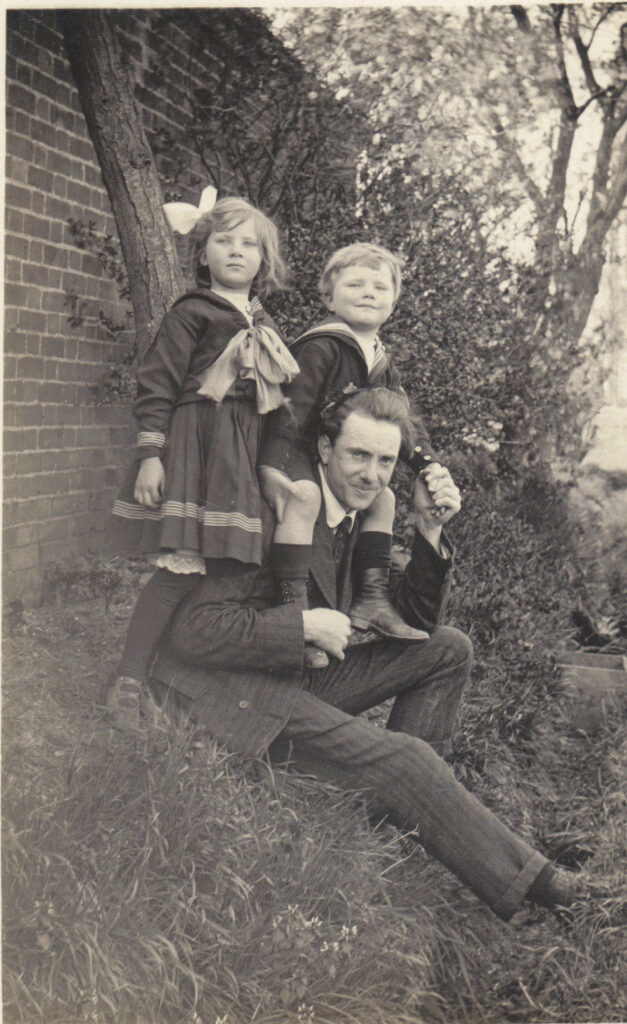

Charles Kennedy Scott was born 16 November 1876 in Romsey, Hampshire, to William Scott (a silk mercer) and Rosa (née Osborne), a schoolmistress. He attended school in Southampton, and was instructed in music by a local teacher. In 1894, Scott entered the Brussels Conservatoire, initially studying violin before changing to organ. Settling in London in 1898, Scott was initially employed as organist and teacher at the Carmelite Priory in Kensington. He married Mary Scott Donaldson on 5 April 1900, going on to have three children.

Visiting the British Library, Scott chanced upon some volumes published by the Musical Antiquarian Society. Inspired particularly by John Wilbye’s First Set of Madrigals (1598), his lifelong passion for Tudor music was sparked. What would become the English Madrigal Choir (and later the Oriana Madrigal Society), began as a group of enthusiasts meeting casually in one another’s homes to sing together. The choir was formally constituted by Scott in 1904, giving two private performances that year at Leighton House, and their first public concert the following year. Between 1905 and 1914, Scott issued fifteen volumes under the title Euterpe: a collection of madrigals and other music of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as producing Madrigal Singing (1907), a manual for members of the society.

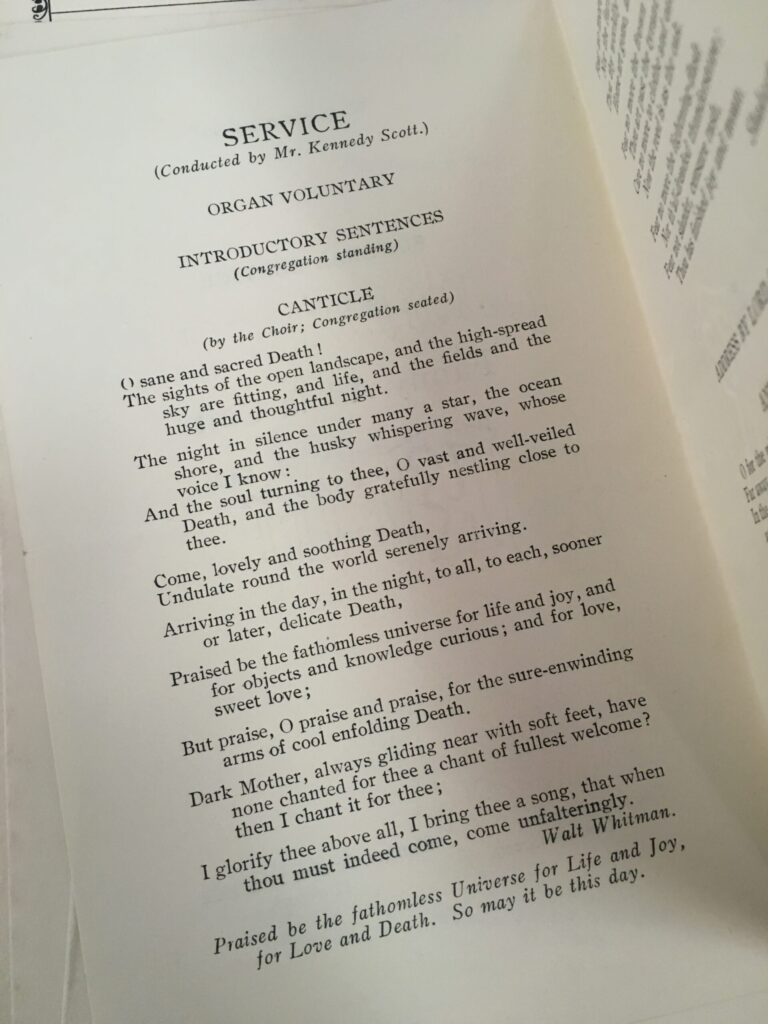

Scott was the musical director and organist at the Ethical Church from 1911 and contributed the second volume of Social Worship (1913), edited by Stanton Coit. During the war, along with Cecil Sharp and Gustav Holst, Scott formed the League of Arts, to continue to provide opportunities for engagement with music, theatre, and art in wartime.

Scott’s belief in the centrality of music is clear in a letter he wrote to fellow members of the Ethical Church in 1915, requesting contributions to the music fund. If the choir were to be lost, he argues

It would be as great a calamity as it would be were we unable to retain our lecturers; for in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to realise our emotional aspirations… I do plead that in the case of our music nothing save the direst extremity should permit of its sacrifice.

In 1918, Scott formed the Philharmonic Choir, about which it was written that Scott’s genius elevated it ‘to a higher cultural level than any other in the kingdom.’ In 1921, Frederick Delius wrote to Scott with obvious admiration:

When I think of all the excellent choruses in Europe, yours is the one which I should most love to bring this work [The Pagan Requiem] to light.’

In 1932, Charles Kennedy Scott led the funeral service for Fanny Adela Coit, and was still actively involved in the humanist movement thirty years later, his last public appearance being a talk for the West London Humanist Society in February 1965. The subject of his lecture was ‘The philosophical sonnets of Shakespeare’.

Charles Kennedy Scott died on 2 July 1965. His obituary in The Times remembered him as

a man of eager personality, definite convictions and quick sympathies. These qualities, together with a certain unworldliness, won the devotion of pupils and choirs.

Can we conceive of anything more perfect than a fugue of Bach or a sonnet of Shakespeare?

Charles Kennedy Scott, Fundamentals of Singing (1954)

Charles Kennedy Scott played a key role in the revival of choral and polyphonic music in England, as well as in fostering the celebrated choir of the Ethical Church. In spite of his apparent ‘unworldliness’, Scott’s own belief in transcendence was not supernatural, but firmly rooted in the artistic achievements of humankind, and the natural marvel of the human voice. This, a profile in The Musical Times, made clear:

Throughout his long life, Kennedy Scott has proved himself a cultured man in the highest sense of the term… [but he] has never lost sight of the human basis of all great music.

Stainton de B. Taylor

Scott’s passion was for the participatory nature of music and singing; for their role in the lived lives of all people. He believed in the value of music and the arts in everyday life, and in the unifying forces of creativity and culture. Scott played an important role in the ethical societies’ experiments in ‘social worship,’ and remained a devoted humanist and lover of the arts to the end.

To those who regard the furtherance of International Good Will and Peace as the highest of all human interests, the […]

Mary Holland was a doyenne of Irish journalism. She epitomised the highest journalistic standards – she inquired, she informed, she […]

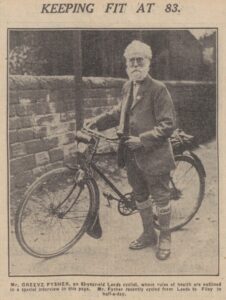

Mr. Fysher was in many respects a remarkable man. His interests were wide, and whatever he took up he carried […]

…having now exceeded the age of three score years and ten, I would say that up to the present I […]