I for one don’t believe in looking regretfully back into the past or forward with illusive hopes into the future, but rather in standing erect in the living present and in trying to distil the excellence out of that, and I believe that with ordinary luck life can be as valuable and as charming as we choose to make it.

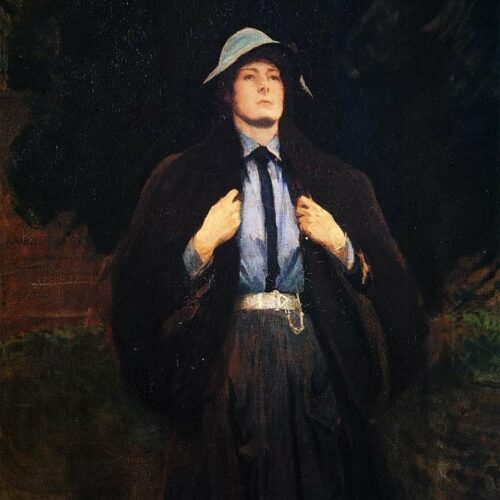

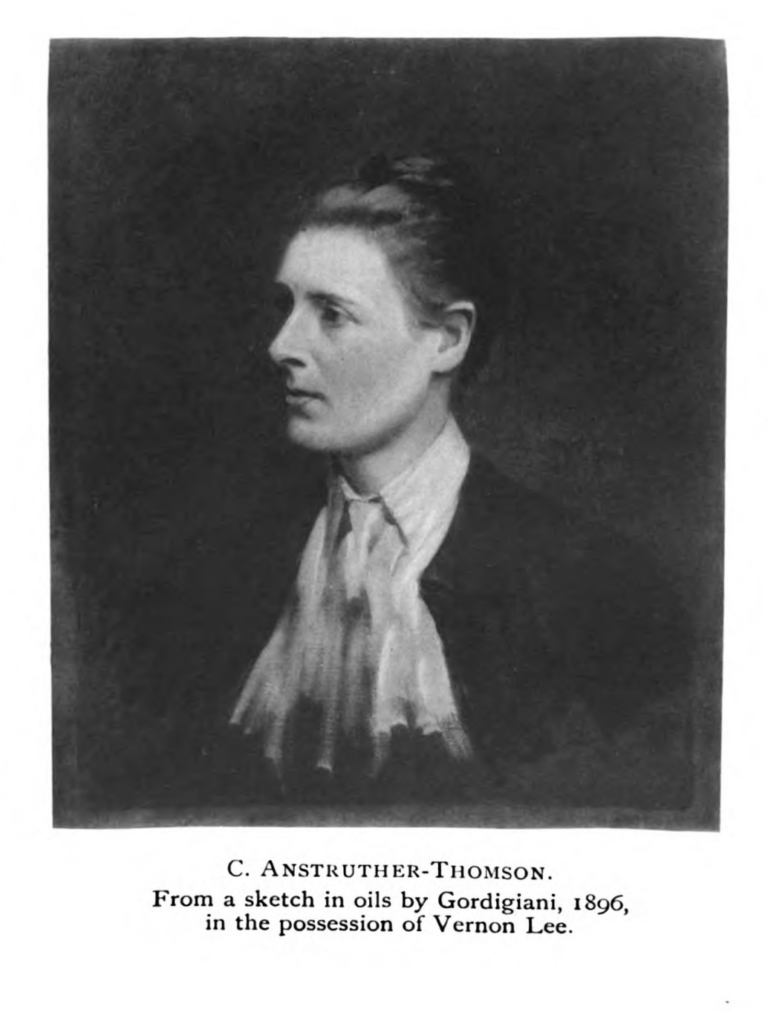

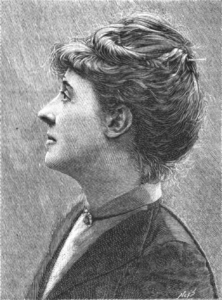

Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, quoted by Vernon Lee in Art & Man (1924)

Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, known to family and friends as ‘Kit’, was an artist, art theorist, and humanist. Along with two close relatives, she was a member during the 1910s of the West London Ethical Society, whose emphasis on beauty and goodness chimed with Anstruther-Thomson’s own philosophy of life and art. This, as epitomised in her writings and in the testimony of her friends, was a humanist philosophy rooted in a clear-eyed observation of reality, a deep empathy with others, and a belief that life has the meaning that we give it.

…she put ordinary remarks in unconsciously unexpected language and she asked unexpectedly abstract questions, as full of intricate whys and wherefores as a clever child’s.

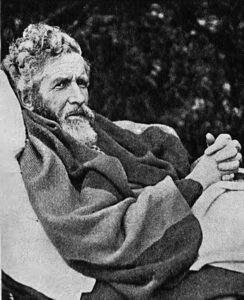

Vernon Lee on Clementina Anstruther-Thomson in Art & Man (1924)

Clementina Caroline Anstruther-Thomson was born at 4 Moray Place in Edinburgh on 15 December 1857, into a wealthy aristocratic family. She was one of seven children born to Caroline Maria Agnes Robina Gray (1833-1882) and John Anstruther-Thomson (1818-1904), the owner of Charleton House, Fife, and renowned as a master of the hounds. In the memoir of Clementina Anstruther-Thomson which introduced Art and Man: essays and fragments by Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, published in 1924, Vernon Lee described the ‘family interests and status’ as being ‘entirely equestrian’. The bloodsport of foxhunting, however, was an aspect which Kit herself quietly disavowed.

Anstruther-Thomson was educated at home, and later studied art at South Kensington’s National Art Training School (now the Royal College of Art), and at the Slade School of Art. She subsequently studied in Paris under French painter Carolus-Duran, and attended talks by her friend, art historian and archaeologist Eugénie Sellers Strong, at the British Museum. In the early 1890s, she wrote, Anstruther-Thomson ‘took to looking at pictures instead of trying to paint them, intending later to make it my business to show the galleries to the East End people in London’. She lectured at Toynbee Hall, and gave a drawing class at Morley Memorial College for Working Men and Women (now Morley College).

In 1887, Anstruther-Thomson met Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), a writer, thinker, and avowed agnostic who would become a lover, collaborator, and lifelong friend. The two embarked on experiments in aesthetics, culminating in the essay ‘Beauty & Ugliness’, first published in the Contemporary Review in 1897, and later reprinted as part of the 1912 collection Beauty & Ugliness, and other studies in psychological aesthetics. In this, Anstruther-Thomson and Lee put forward a theory of art based on its physical impact on the body, drawing on careful observations Anstruther-Thomson made of her own physical responses to works of art, sculpture, and architecture.

In 1910, Clementina Anstruther-Thomson became a member of the West London Ethical Society, then meeting at its ‘Ethical Church’ in Bayswater. Also members were two of Anstruther-Thomson’s close relatives: her sister-in-law, Agnes Anstruther (wife of Charles St. Clair Anstruther, Clementina’s brother, and a member since 1896) and her niece, Grizel Margaret Anstruther. In the Ethical Church, the West London Ethical Society experimented with ‘social worship’, and designed the building to embody their secular reverence for examples of the good, the true, and the beautiful. Stanton Coit, the Society’s head, sought to redefine the concepts of god and religion, dispensing with the idea of a supernatural origin for these ideals, and revering them instead for their own sake. Anstruther-Thomson’s passionate interest in the arts bore much in common with this. As Lee wrote:

… if her own attitude towards Beauty might almost be called religious, this was only because she recognised in Beauty something transcending ordinary life… but these sacred powers were natural, human and explicable: unlike most other mysteries, these beneficent rites of poetry and art lost none of their wonder and holiness by becoming intelligible. Indeed, Kit’s whole idea of initiation into perfect communion with beautiful things was to explain why, or at least how, we come to “feel” them to be “beautiful.”

Moreover – and in this Kit’s purely secular and extremely modern views exactly reversed those of her adored Ruskin – to explain that, in whatever “natural” objects we might find it, this quality of being “beautiful” was always dependent on man’s activities; its recognition and enjoyment requiring an act of minor creation inferior only to the creation by the artist…

Vernon Lee in Art and Man: essays and fragments by Clementina Anstruther-Thomson (1924)

In art, and particularly in classical art, Anstruther-Thomson found the great meaning of her life. She described standing before an object ‘in a little railed off piece of eternity’, with rapt attention in which ’the very act of being alive, of living, becomes a wider, a keener, a more complex act’. She did not see this, however, as a rarified or merely private activity. Lee wrote that:

however intensely attracted [Anstruther-Thomson was] by the theoretic problems of art, I doubt whether she would have given herself up to them rather than to nursing, doctoring or some sort of social organizing, if she had not persuaded herself that the accumulated treasures of art must be made accessible to the less privileged classes, and that this could be compassed by explaining the manner in which works of art act on our spirit.

Like many others within or associated with the ethical societies, Anstruther-Thomson was actively involved in a number of progressive causes. During the 1880s, she worked in support of the Bryant & May matchgirls’ strike, alongside feminist and trade unionist Clementina Black, challenging the dangerous conditions and low pay in the production of matches. According to Lee, Anstruther-Thomson’s mind ‘never ceased running on social reform’. Years later, she became involved with the Union of Democratic Control, whose membership comprised many prominent humanists, including H.N. Brailsford, Bertrand Russell, and Ramsay MacDonald. The UDC – formed in response to the outbreak of the First World War – brought pacifists, socialists, and Liberals together to act as a pressure group, calling for greater public scrutiny in foreign affairs and diplomacy. Lee too was involved in the UDC, serving on its General Council. In this shared effort towards peace and international understanding, Lee described she and Anstruther-Thomson as recapturing ‘our original perfect understanding in all of the fundamental matters of life’.

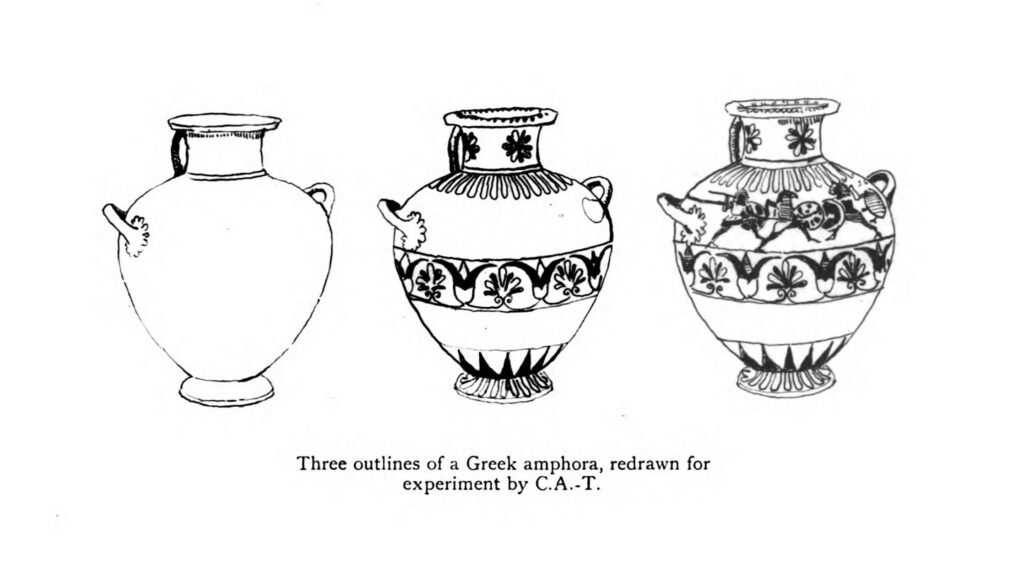

What is it that gives us this realization of the past? And why do we anticipate the future in this expectant way? They are strange things to find in a picture!

Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, ‘More about Greek vases’ in Art & Man (1924)

Clementina Anstruther-Thomson died in London on 7 July 1921, and is remembered on a family plaque in Kilconquhar, Fife. Along with so many freethinking women of the 19th century, including many fellow members of the ethical societies, she had lived by a humanist philosophy of active goodness, based not on theological doctrine or the premise of an afterlife, but on empathy with other human beings and a belief that a finite existence only enhanced the significance of the present moment. For Anstruther-Thomson, this was captured best in close engagement with art, as well as in a life dedicated to the caretaking of others, and to aspects of social reform. Her life and character were most fully described in Vernon Lee’s introduction to Art & Man, who was nevertheless conscious of not ‘intruding over-much on her aloofness’. Of Anstruther-Thomson’s death, aged 63, Lee wrote:

I confess that at the moment of her death I hoped that her ashes might be mingled with the earth of those Fifeshire beech-groves and hornbeam hedges where I had first got to know her, and within sound of the Forth, for whose sake the noise of any sea was so dear to her. But I have come to recognize that my friend, who had so fine a sense of ceremonial where others came into play, and who never so much as returned me a stamp or a sixpence without adding a flower or a green leaf to it, would have hated anything out of the common, any “fussing” where herself was concerned. And that it is more consonant with her whole personality that she should have no last whereabouts save in the minds of those who have known her.

Art & Man: Essays and Fragments by Clementina Anstruther-Thomson (1924) | HathiTrust

Belief in the power of man to choose his direction of change: this is the creed of the future, and […]

The old teaching was that we must worship not truth, beauty and goodness, but their source, and that their source […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]

It has been suggested that matter is capable of destruction, that every atom is destined to be dissolved away in […]