Constance Naden, Further Reliques (1891)

…the only universal truths which exist are the fundamental laws of the mind. Philosophy, then, which is the science of the fundamental laws of the mind, forms the true basis of practical right conduct, […] all right conduct, when analyzed, will be found to rest on the ultimate principles of reason.

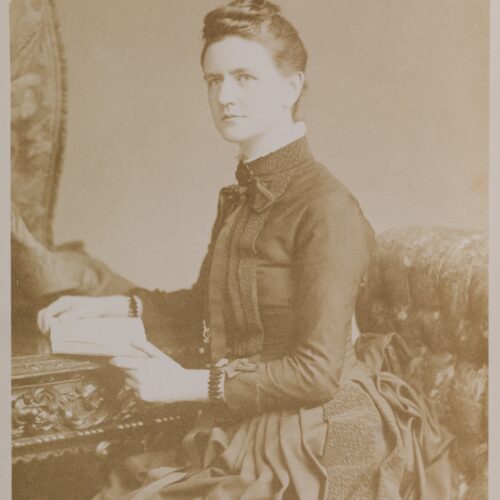

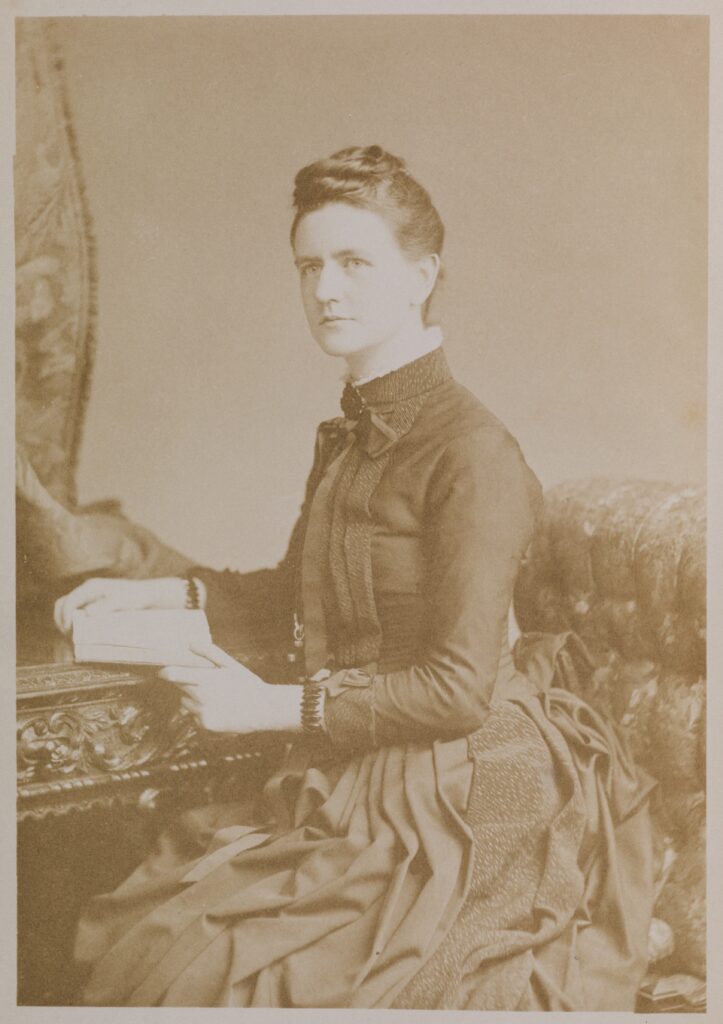

Constance Naden was an interdisciplinary thinker whose contributions to philosophy, poetry, and social science in the 1880s speak to her commitment to humanist endeavour. She identified as an atheist and advocated an idealist-materialist philosophy, which drew upon contemporary science to articulate her belief in universal unity and the centrality of reason and sympathy in guiding human behaviour.

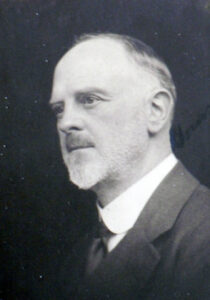

Naden was born in Birmingham in January 1858 and was brought up by her Baptist grandparents, who sent her to a Unitarian school. Upon leaving school in 1875, she travelled around Europe, met her life-long friend and fellow philosopher Robert Lewins, began learning German, Latin, and Greek, and started taking an interest in science and freethinking philosophies. She returned to studying in 1879, first taking classes in botany, French and German at the Birmingham and Midland Institute and then enrolling at the Mason College of Science (which later became the University of Birmingham), where she studied geology, chemistry, physics, zoology, and physiology between 1881 and 1887. In 1887 Naden was made the first female Associate of the college in recognition of her achievements. Her studies were bookended by the publication of her two volumes of poetry – Songs and Sonnets of Springtime (1881) and A Modern Apostle; The Elixir of Life; The Story of Clarice, and other poems (1887) – in which she expressed her lyric engagement with the natural world, her comic observations about modern society, and the development of her philosophical ideas.

Naden’s scientific education was crucial to her philosophical thinking. As William Tilden (Professor of Chemistry) declared: ‘No inducements seemed sufficient to prevail upon her to become a mere scientific specialist’ – she studied to acquire knowledge of each discipline as a foundation for her synthetic philosophy (Memoir 68). In the first half of the 1880s she worked with Lewins to propose an atheist philosophy called Hylo-Idealism, which focused on finding ‘unity in diversity’. In an essay published in the Journal of Science in 1883, she explained the central tenet of this ‘Brain Theory of Mind and Matter’:

Man is the maker of his own Cosmos, and all his perceptions – even those which seem to represent solid, extended and external objects – have a merely subjective existence, bounded by the limits moulded by the character and conditions of his sentient being.

Induction and Deduction, 157

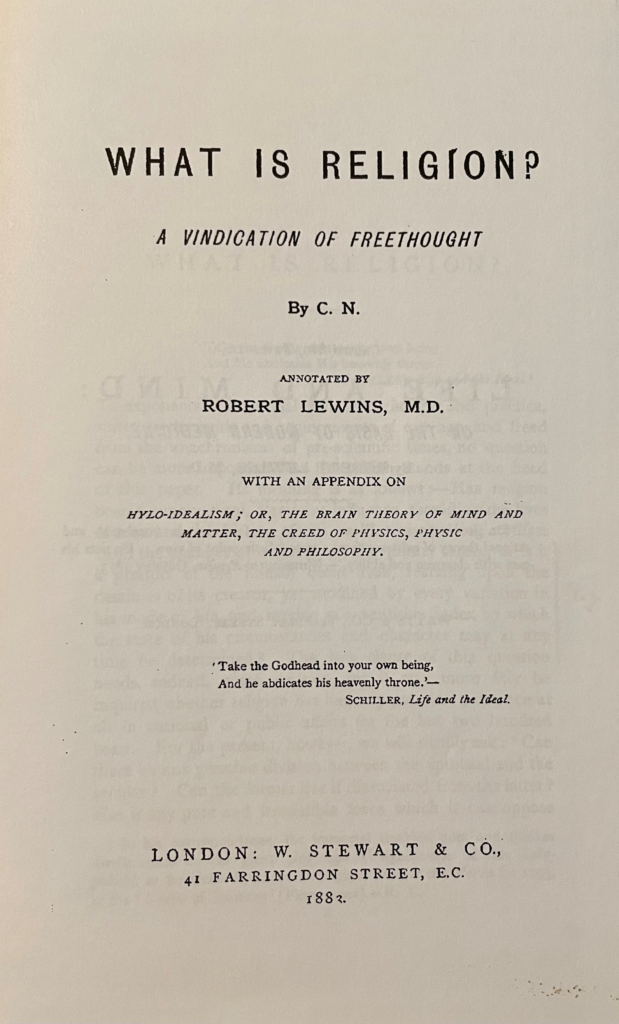

Her thinking was influenced by German Romantic philosophers, nineteenth-century freethinkers (such as Charles Bradlaugh, Annie Besant, and George W. Foote), and other contemporaries such as philosopher, sociologist, and agnostic Herbert Spencer. Her choice of publication venues indicates her connections to the freethought movement, with essays and poems appearing in Our Corner, Secular Review, and the Agnostic Annual across the 1880s. Her 1883 pamphlet What is Religion? A Vindication of Freethought was published by William Stewart Ross, better known by his pseudonym Saladin. Under the anonymity of her initials, Naden critically assessed the phenomenon of religion through the lenses of anthropology, philosophy, and history. She also attempted to explain society’s dislike of atheism, using the example of Bradlaugh’s exclusion from parliament to illustrate how late nineteenth-century Britain could be characterised as ‘a nation of practical secularists [who] can tolerate passive religion better than active atheism’ (Further Reliques, 108). She concluded by showing how the claims of religion can be undermined with the application of ‘reason’ and a hopeful call to instead ‘make science itself a well-spring of ideal truth’ (Further Reliques, 133).

Throughout her career, Naden argued that ethics and morals are entirely separable from religious doctrine. It is here that her humanist standpoint is most clear. For example, in ‘Evolutionary Ethics’ (1887) she employed an evolutionary and sociological understanding of human behaviour to show that ‘no moral advance can take place except by means of rationally guided sympathy’ (Induction and Deduction, 135) while her theory of ‘Cosmic Identity’ (only published after her death) was grounded in the idea that ‘My character could not even exist apart from Society, since it is constituted by the relations of my feeling, thought and action, to the lives of others’ (Further Reliques, 180).

Upon the death of her grandmother in 1887, Naden left Birmingham to travel across Europe, the Middle East and India. She then settled in London, where she became involved in more political activities. These included campaigning for a Liberal MP, supporting social progress and female education in India, and actively supporting women’s suffrage. In the Women’s Penny Paper (12 January 1889), Naden is reported to have argued the case for women voters on the basis that ‘the masculine point of view needed counteracting by the feminine’. In spring 1889, Naden’s companion Madeline Daniell wrote to George Bernard Shaw regarding the two women’s attendance of Fabian Society meetings. They had gone ‘hoping to hear some earnest schemes, or proposals whereby the present horrible wrongs can be righted, and the world made better’ but were disappointed by the lack of discussion of practical activism. Naden’s ethic of human fellowship and desire to promote solidarity through good works is clear.

William R. Hughes, a friend and fellow thinker, wrote that Naden’s death in December 1889 ‘deprived the world of a fine and original thinker, Birmingham of its most gifted daughter, [and] progressive Science of a most distinguished worker’ (Memoir, 3). Obituaries in the local and national press were followed by a memoir written by four of her friends, and Lewins rapidly commissioned a marble memorial bust by William Henry Tyler, which originally sat in the Mason College library and is now displayed in the Cadbury Research Library at the University of Birmingham.

Her writings faded from view before the end of the nineteenth century, however, and it is only in the past three decades that her poetry and philosophy have come to be remembered. Nonetheless, Naden’s dedication to the ideal of a secular society with its foundations in rational thought rather than dogmatic faith (whether religious or secular) remains relevant. Her endeavours were rooted in ‘the reconciliation of poetry, philosophy, and science’ (Further Reliques, 126) – in Naden’s life and writings we find a model for working towards this goal.

By Clare Stainthorp

This article draws from the book Constance Naden: Scientist, Philosopher, Poet (2019) and is supplemented by ongoing research into the periodicals of the nineteenth-century freethought movement.

William R. Hughes, Constance Naden: A Memoir (London: Bickers and Son; Birmingham: Cornish Brothers: 1890)

Constance Naden, The Complete Poetical Works of Constance Naden, edited by Robert Lewins (London: Bickers and Son, 1894)

Constance Naden, Induction and Deduction: A Historical and Critical Sketch of Successive Philosophical Conceptions Respecting the Relations Between Inductive and Deductive Thought and Other Essays, edited by Robert Lewins (London: Bickers and Son, 1890)

Constance Naden, Further Reliques of Constance Naden: Being Essays and Tracts for our Times, edited by George M. McCrie (London: Bickers and Son, 1891)

Clare Stainthorp, Constance Naden: Scientist, Philosopher, Poet (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2019)

Clare Stainthorp, ‘Seeing Science in the Stars: Constance Naden’s sonnets and the night sky’, Lucy Writer, 20 May 2020.

Stanton Coit was a pioneer of the Ethical movement in England and the founder of the West London Ethical Society, […]

Born Lotte Reyersbach in Oldenburg, Germany in 1923, Sharley McLean arrived in England on the Kindertransport as a teenager. Both […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

Bessie Mabbs was a teacher, school principal, and active member of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), chairing […]