Without any great effort of thought, I believe that I could, in an instant, propose other systems of cosmogony, which would have some faint appearance of truth; though it is a thousand, a million to one, if either yours or any one of mine be the true system.

from Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779)

David Hume is regarded as one of the most significant philosophers to write in English, and was a leading figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. Despite acquiring the role of patron to the Scottish Church in his later life, Hume was sceptical of religion and advocated for the separation of Church and state. He is considered one of the staunchest critics of religion in his time, challenging the idea of miracles, human nature, and God-given morality.

Hume was not the first to write in such a manner and was influenced by the works of the late Roman Republican Cicero and the 17th century French philosopher Nicholas Malebrance. However, his work helped further the development of philosophical thought that sought to challenge religious authority and focus on the importance of evidence, exercising significant influence on freethinkers and humanists that followed him.

David Hume was born in Edinburgh on 7 May 1711. He attended the University of Edinburgh at the age of 11, considered young even then. After studying for three to four years he left briefly to study law, before taking up philosophy. Although now regarded as a renowned philosopher, Hume did not find much success with his early work. During his time in France (1734-37), he wrote the Treatise of Human Nature, and published it anonymously in 1739-49. However after disappointing sales he summarised the main points in a new piece titled Abstract, which was again published anonymously. Further disappointment came in Hume’s life when he failed to become a professor in philosophy at both Edinburgh (1745) and Glasgow (1752) universities and he would not find a full time job until he was in his 40s.

David Hume’s later life would prove to be more successful. After publishing two volumes of essays, Essays, Moral, Political and Literary, and rewriting parts of the Treatise, he published a very successful collection of essays in 1752 under his own name. These, under the title Political Discourse, focused on political and economic concerns. In 1752 Hume was appointed Keeper of the Advocates Library in Edinburgh where he started to write one of his most famous pieces of work: History of England (1754-62). From 1763-66 he served as the Secretary and then as Charge d’affaires at the British Embassy in Paris. It was during this time he became friendly with great philosophers and freethinkers such as Diderot and Rousseau. On his return to London he became Under Secretary of State, handling diplomacy with northern foreign powers such as Russia.

Contemporary writers viewed Hume as an atheist, or at least distinctly un-Christian. Whether Hume himself was a believer or not, his position of scepticism was symptomatic of the values of the Enlightenment brought to bear on religion, and influential on subsequent freethinkers. Hume was critical of religion and the role it played in 18th century politics and the daily lives of people. He challenged the church on miracles, which he believed to be impossible, and highlighted the lack of evidence proving their reality. He argued that truth could be found through investigation and pushed for evidence to be presented. Hume wanted people to question the idea of the supernatural and provoke a discussion of rational thinking, instead of simply believing the words of someone else.

Hume also challenged the idea that religion created morality and viewed his own morals as simply common sense. He argued that morality could not be discovered or produced and further stated that religion, when distorted, does more damage to people’s lives than good. Examples of such distortion would be the extremist factionalism within the Christian Church; fundamental or authoritarian Protestants; and repressive superstitious Catholicism.

Hence the greatest crimes have been found, in many instances, compatible with a superstitious piety and devotion: Hence it is justly regarded as unsafe to draw any certain inference in favor of a man’s morals from the fervour or strictness of his religious exercises, even though he himself believe them sincere.

David Hume, Natural History of Religion (1757)

In 1769 Hume retired to Edinburgh, revised his History and worked on his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religions, which was modelled on work by Cicero and published posthumously in 1779. It was during his retirement that Hume hosted the likes of Benjamin Franklin and Adam Smith, whose work Hume greatly influenced. David Hume died on 25th August 1776.

Just as Hume was influenced by Cicero, modern day philosophers, politicians, activists, historians, and writers have been influenced by Hume’s work and his philosophical approach to issues such as morality and religion. His sceptical approach and emphasis on the use of evidence to demonstrate fact remains central to the humanist approach today.

His work was admired by many philosophers and secular movements. Adam Ferguson (1723-1816), James Madison (1751-1836) and Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804) all studied Hume’s writings, and the leaders of the French revolution admired his secular approach to governance. His views on nature, freedom and determinism, reason, and sentiment are still debated among philosophers today, and continue to exert strong influence on the ideas of many.

Bishopsgate Institute was built ‘for the benefit of the public’ in 1894, intended to provide opportunities for education and recreation […]

Bessie Braddock was a trade union activist and politician, who devoted her life to improving the lives of others. She […]

Object: to provide an ‘open forum’ for the fearless consideration of modern problems relating to ethics, sociology, education, political theory, […]

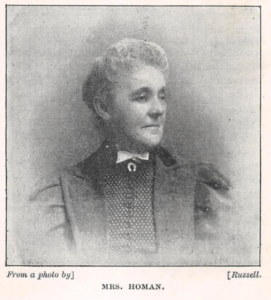

Ruth Homan was an educationist, women’s welfare campaigner, and one of the founding members of the West London Ethical Society […]