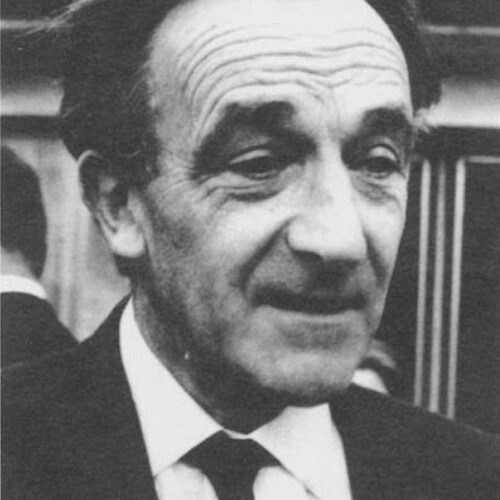

In my experience he was the kindest of men, far too modest about his own contributions and always prepared to ask fundamental questions, without accepting any of the existing theories as adequately proven.

Sir Roger Bannister, ‘Tribute to David Oppenheimer’ in Clinical Autonomic Research 1, 261 (1991)

By Peter Faulkner, originally published in New Humanist, September 1991

David Oppenheimer, who died recently, was a distinguished neuropathologist, a gifted musician, and a rationalist. He was an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association.

There was a tension between his scientific work and music throughout his life. While at Balliol College, Oxford, he wrote music for productions of Oedipus and Alcestis. He had a scholarship to read classics, but changed to PPE and then took a B. Mus.

In 1939 he objected to taking part in the war on the grounds that killing people was wrong — a position that it was particularly difficult for an atheist to hold. He volunteered for the Fire Brigade Heavy Rescue team and worked through the blitz in Holborn and Finsbury — seeing the terrible sight of mutilated bodies. He later worked in a hospital unit in Holland and Germany. When he returned to university life, his experience had led him to change course and to study medicine. After completing his studies in Oxford he moved to London Hospital as a House Surgeon. His musical skill was put to use in writing for student shows.

He returned to Oxford to study anatomy, where he joined a team working on the study of the nervous system. He moved into neuropathology, becoming a highly regarded teacher and researcher. When a fire destroyed his huge source of specimens and information, he steadily embarked on building them up again. The summit of his achievement in this field was his magnum opus — written jointly with Margaret Esiri — the Diagnostic Neuropathology. In his retirement he worked with Professor G. A. Wells on the publication of books based on the manuscripts of their teacher F. R. H. Englefield between 1977 and 1990. The first was on the origin and nature of language, the second on “the thinking process in man and in his closest mammalian relatives”. The third, a series of essays “criticising pretentious nonsense in literary critics, theologians and philosophers” was entitled The Critique of Pure Verbiage.

Despite wielding a sharply critical pen, he was “the kindest and gentlest of men”, sharing his mother’s view that the ultimate vice is cruelty. Professor Wells spoke at Oppenheimer’s secular funeral:

I owe a lot to David in respect of my own work, as we shared what I will call a critical interest in Christianity — its origins, its development, its claims and the strange contortions of some of its latter-day apologists. These contortions much amused him, and he would frequently send me representative cuttings from newspapers or journals for, as he put it, my secret sottisier. Now I shall have to do without David’s encouragement, advice and criticism. I know that I am not alone in this situation, and I know too that we shall not find it easy. We can but remain grateful for the enrichment he has brought us, and for the immediate rapport with each other that having known him gives us.

Order is our Basis; Improvement our Aim; and Friendship our Principle. Annual Report of the Neighbourhood Guild, 1895 Leighton Hall […]

The object of this Society is: To increase the knowledge, the love, and the practice of the right. Its bond […]

… a man who thinks himself bound to all offices of Humanity. Ephraim Chambers, self-composed epitaph Ephraim Chambers was an […]

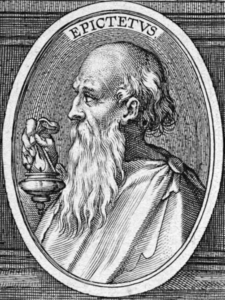

For I am not everlasting, but a human being, a part of the whole as an hour is a part […]