I was educated among the Saints; and I now live, thank God, among Sinners.

David Williams, Essays on Public Worship (1773)

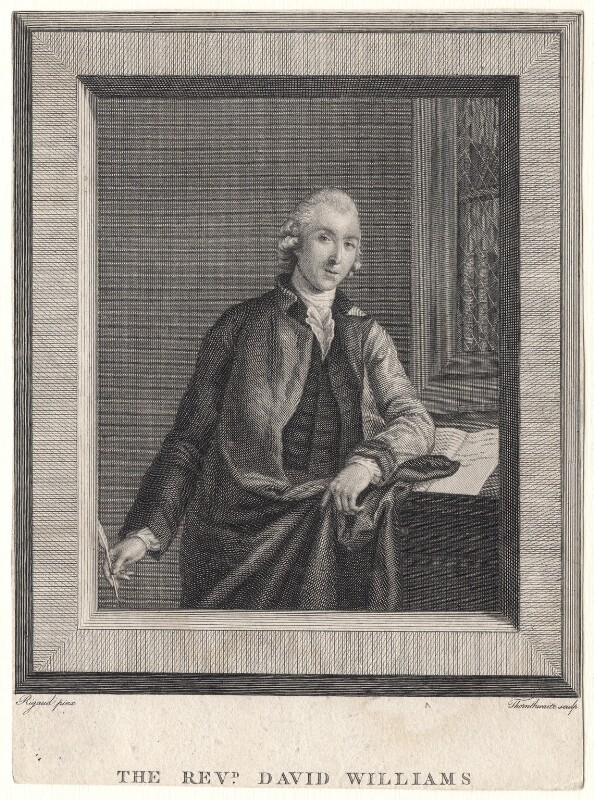

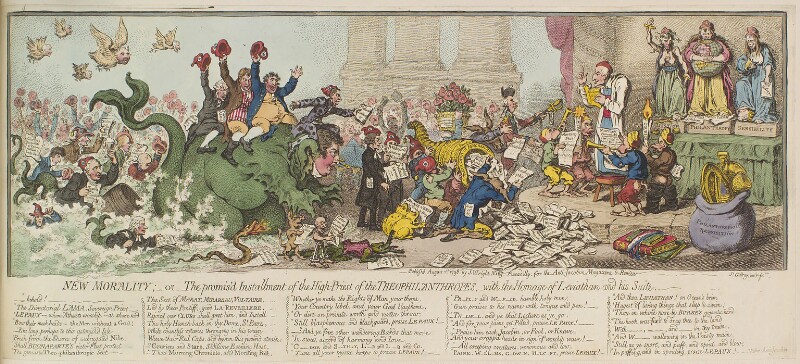

David Williams was a Welsh philosopher and writer, who progressively shed the dissenting Christianity of his early life in favour of a deistic ‘natural religion’. Benjamin Franklin, a friend of Williams, nicknamed him the ‘Priest of Nature’, and the two were co-founders of the deist Club of Thirteen. Today, Williams is best remembered as the founder of the Royal Literary Fund, a benevolent fund for writers, though he was also a significant thinker and pamphleteer. In his advocacy of a non-sectarian form of public worship, which would bind together the community on the basis of shared moral principles, he anticipated some of the humanist ideals of the positivist and Ethical movements, cementing his interest for humanists today.

It is not possible to regulate by authority, the real assent of the mind.

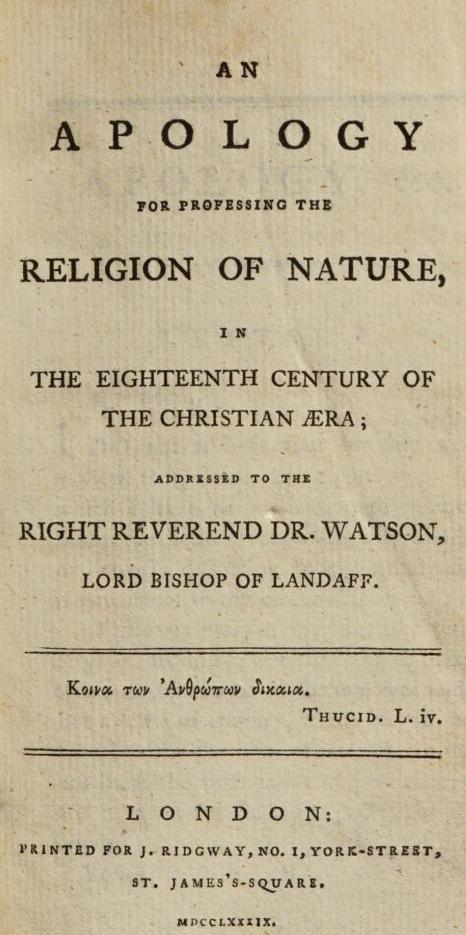

David Williams, An Apology for Professing the Religion of Nature, In the Eighteenth Century of the Christian Era; Addressed to the Right Reverend Dr. Watson, Lord Bishop of Landaff (1789)

David Williams was born in 1738 in Eglwysilan, between Caerphilly and Cardiff, in Wales. Educated in the local school kept by another David Williams, a dissenting minister, it was his father’s wish that he entered the ministry himself. Williams honoured this, becoming a student between 1753-7 at the Carmarthen Academy, which was known for its heterodoxy. Although Williams acted as a Presbyterian minister in Frome, Exeter, and Highgate, he ultimately abandoned the ministry and, in 1773, instead opened a school in Chelsea. The following year he wrote his Treatise on Education, but gave up the school after his wife Mary Emilia’s death in 1775.

Williams’ educational writings were not his first, and earlier pieces had brought him to the attention of Benjamin Franklin, who stayed with Williams in his Chelsea home. With Thomas Bentley, a manufacturer and fellow religious dissenter, the men founded the deist ‘Club of Thirteen’ in 1773. In common with other deists, Williams rejected concepts of biblical revelation. Some years later, in 1789, he described his beliefs in An Apology for Professing the Religion of Nature, In the Eighteenth Century of the Christian Era; Addressed to the Right Reverend Dr. Watson, Lord Bishop of Landaff, writing:

That I do not believe in the articles and doctrines of the English church, or the authenticity of the revelation on which they are said to be founded, I am disposed to declare. And I wish to know why this declaration should excite resentment, and render me liable to disadvantages? I will not allege a suspicion generally entertained, that real and actual belief is not necessary to subscription, if the habit be induced early. But I should be highly grateful if I could be directed in the mode of subscribing to doubtful or unintelligible propositions, without destroying the peace of my mind… I presume to address to the most decent defender of Christianity, my apology for not assenting to its pretensions, and for adhering to the religion of Nature.

This ‘religion of nature’, Williams hoped, could be the basis of a secular form of worship, which would unite people through shared moral ideals, rather than divisive religious tenets – an interesting precursor to Auguste Comte’s humanist ‘religion of humanity’, and Stanton Coit’s ‘social worship’.

In 1776, Williams opened a chapel, using his Liturgy on the Universal Principles of Religion and Morality as its guiding text. As Damian Walford Davies writes in Williams’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry, the liturgy:

…avoids all dogmatic statements of belief beyond an acknowledgement of the wisdom and goodness of a supreme intelligence and the moral obligations of a simple deism that celebrates nature as implying the existence of God. All specifically Christian doctrines of faith are carefully excluded.

Although the chapel closed in 1780, the services moved to a Charing Cross coffee house, and Williams remained involved with various apparent successors. These included a Philosophical Society, a Liberal Society, an Academy of Sciences and Belles-Lettres, and a School of Eloquence. Among Williams’ admirers (including of his Liturgy) were other notable deists abroad, including Voltaire and Rousseau.

In other ways too, Williams’ ideas bore much in common with those of later freethinkers. In his 1789 Apology, Williams made a powerful argument against state sanctioned religion, foreshadowing many of the lines of argument taken up by champions of press freedom during the first decades of the 19th century. People should not be prevented, Williams believed, from applying their own reason to matters of religion. He argued:

That the state should support some religion, is a false principle, which I shall not at this time discuss. If it were true, why attempt it by a mode impracticable and impossible; which must nip integrity in the bud, and deprave the most valuable tendencies of the human mind? It is not possible to express a series of propositions to which the varying faculties of men can yield the same assent; and to offer recompense for belief, is the expedient of error and imposture… If the articles of the church, and the doctrines of revelation cannot support their credit without the aid of mercenaries, why not render the conditions of their services practicable?

Williams also criticised the hypocrisy of the religious in condemning people who didn’t share the tenets of their faith to a lifetime of disapproval (and to eternal punishment thereafter), despite claiming to be moral. In an imagined exchange between the author and ‘Bigot’, he put forward his argument:

Bigot: There is an almighty power which will condemn you for your unbelief.

Author: That power, I suppose, you call the devil.

Bigot: No – I call him God!

Author: Call him what you please; his spirit must be that of malignity: – and I neither fear nor love him.

Williams supported himself with writing and education: tutoring private pupils, delivering public lectures, and publishing on a variety of subjects. In 1790, he established the Literary Fund (now the Royal Literary Fund), to support writers in need. Williams had been moved by the 1787 death in a debtors’ prison of Floyer Sydenham, a scholar and translator of Plato.

Williams spent his final years living at the Literary Fund’s headquarters in Soho, where he died on 29 June 1816. He was buried at St Anne’s Church, Soho, his will expressing a desire to be interred ‘in as plain and frugal a manner as the rules of decency will admit of’.

I know this liberty will be deemed an offence; that declining the belief and the advantages of Christianity, is criminally denominated; and that infidel, and enemy, are synonymous terms in the language of bigotry.

David Williams, An Apology for Professing the Religion of Nature (1789)

David Williams argued that fear of punishment was an inadequate, and ineffective, means of encouraging genuinely virtuous behaviour (even if it could produce outward displays of goodness). Instead, it was reason combined with humanity which led people to live morally – a very humanist idea. He defended the individual’s right to pursue truth for themselves, and to refuse to adhere to those religious practices they could not square with their own conscience. In all of this, and in common with other deist thinkers, Williams provides an important example of 18th century scepticism, and introduces a secular conception of morality which strikingly anticipates the positivist ‘religion of humanity’, and Felix Adler’s ‘Ethical Culture’, which gave rise to today’s organised humanist movement.

Our History | The Royal Literary Fund

David Williams | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

David Williams, littérateur and political pamphleteer | Dictionary of Welsh Biography

Reverend David Williams | Art Collections Online, National Museum Wales

Whitney R. D. Jones, David Williams: the Anvil and the Hammer (1986)

J. Dybikowski, On Burning Ground: an Examination of the Ideas, Projects and Life of David Williams (1993)

David Williams, An Apology for Professing the Religion of Nature (1789)

15-Minute Heritage: Caerphilly’s Memorials and Parks (includes memorial obelisk to David Williams)

Is being rewarded for maintaining certain articles as matters of faith, and being punished, or suffering for opposing them, proper […]

Everywhere man blames nature and fate yet his fate is mostly but the echo of his character and passion, his […]

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]

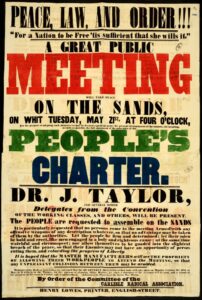

A mass working class movement for universal male suffrage Read more Chartist Ancestors and Women Chartists Chartism by David Avery […]