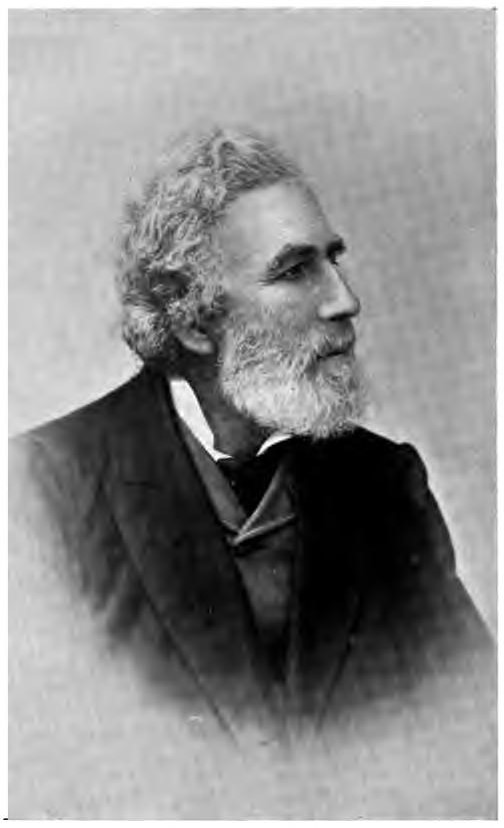

The radical publisher Edward Truelove found himself in court more than once defending freedom of belief and expression. He believed, in the words of his friend and colleague George Jacob Holyoake, that ‘the search for truth is the noblest pursuit of man and the publication of it a duty.’ A follower of Robert Owen, and participant in the experimental Queenwood community, Truelove remained an admirer of the reformer all his life, and was an advocate of the principles of equality, reason, and reform which sat at the heart of Owenite philosophy. Truelove’s humanism was embodied in his outspoken atheism, defence of fundamental human rights, and active concern for humanity.

Edward Truelove was born to John and Sarah Truelove in Marylebone, London, on 29 October 1809. He married Harriett Potbury in 1840. Harriett, a signatory (along with her daughter) on the 1866 suffrage petition presented to Parliament by John Stuart Mill, also acted as secretary to the John Street Institution – a radical meeting place for which Edward Truelove was bookseller. She was also a friend and correspondent of Florence Nightingale, who visited the bookshop she and Edward kept together.

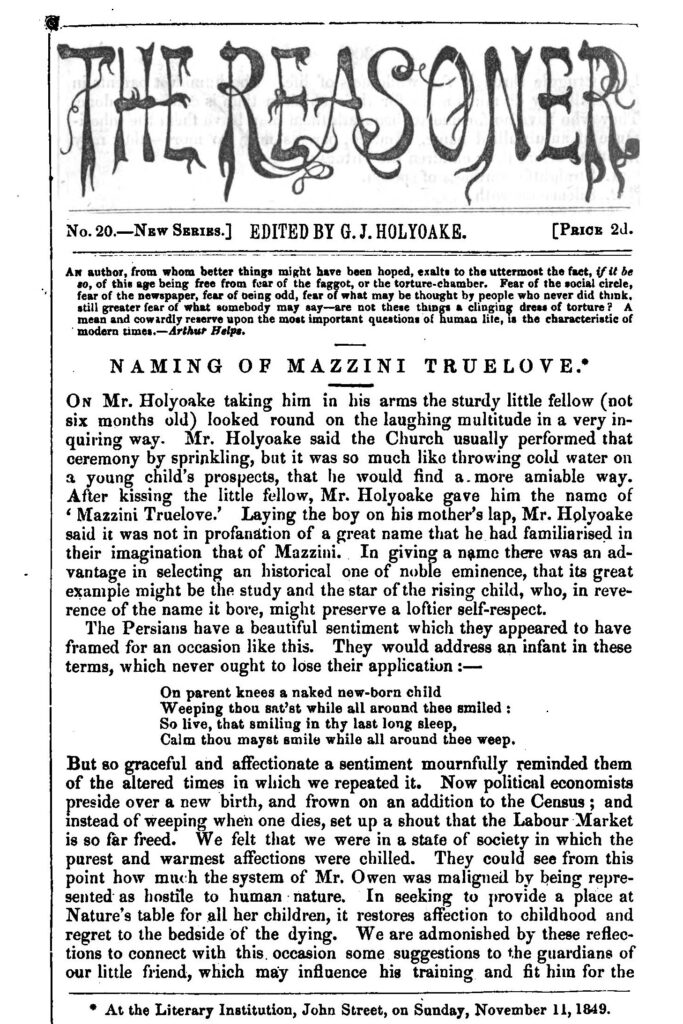

On 11 November, 1849, George Jacob Holyoake carried out a secular naming ceremony for the Trueloves’ son, Edward Mazzini (named to honour the Italian revolutionary Guiseppe Mazzini). The ceremony was reported in Holyoake’s The Reasoner:

Mr. Holyoake said the Church usually performed that ceremony by sprinkling, but it was so much like throwing cold water on a young child’s prospects, that he would find a more amiable way… In giving a name there was an advantage in selecting an historical one of noble eminence, that its great example might be the study and the star of the rising child, who, in reverence of the name it bore, might preserve a loftier self-respect.

Holyoake described the duty of parents as being to educate their children by example; to ‘Cultivate ‘“independence of ideas” and “the law of kindness.”’ For Holyoake and Truelove, lifelong followers of Robert Owen, this naming ceremony was both a celebration of new life, and a conscious vindication of Owen’s ideas.

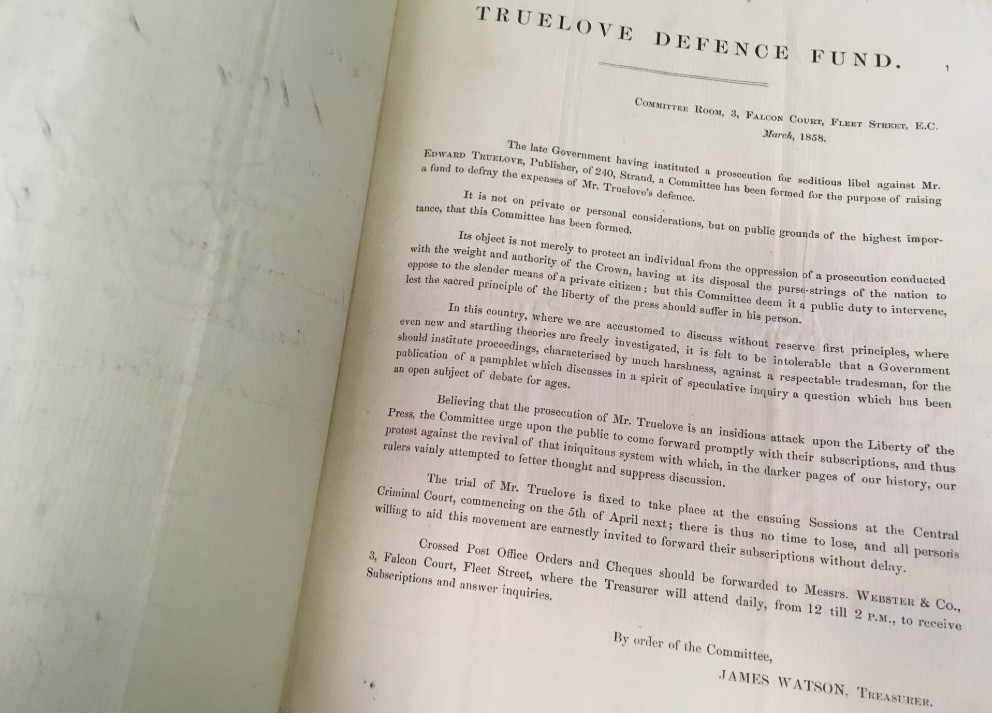

Describing Truelove’s philosophy as a bookseller and publisher, Holyoake later wrote that, ‘Any honest, well intended work, originating in the byways of independent thought was welcome to him.’ As such, Truelove sold a number of controversial works, including by Paine, Voltaire, and D’Holbach. In 1858, Truelove was charged with seditious libel, following the publication of William Edwin Adams’ Tyrannicide: Is it justifiable? This, it was alleged, incited violence against French Emperor Napoleon III. A ‘Press Prosecution Defence Committee’ was established, and a defence fund launched, with Charles Bradlaugh (the committee’s secretary) writing that ‘It would be a mark on us for years to come if we left poor Truelove to fight the battle of the press alone.’ In the end, Truelove was acquitted.

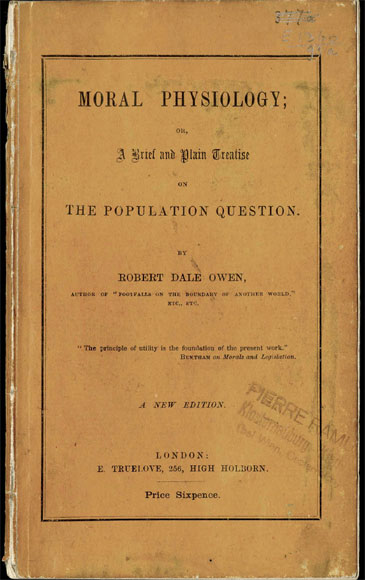

A founding member of the Malthusian League, which advocated for the necessity of, and right to, methods of contraception, Truelove also published materials promoting birth control. In 1878, he was brought to trial for publishing Robert Dale Owen’s Moral Physiology. At the same time, Bradlaugh and Annie Besant were themselves in court over The Fruits of Philosophy, because of which Truelove’s own case was postponed. This time, Truelove, aged 70, was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment and a fine of £50. The prosecution under obscenity laws for a medical text, directed towards the public good, was decried by Truelove’s supporters as ‘a monstrous outrage on the common sense of Englishmen, and a grossly unconstitutional stretch of the English law.’

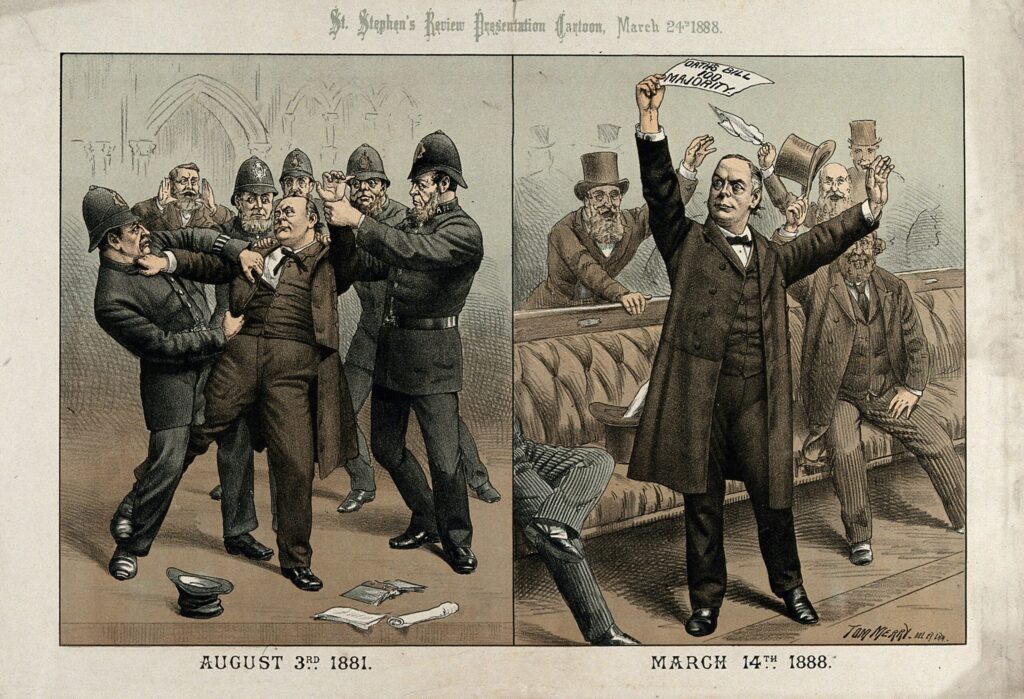

Further common ground between Truelove and his friend and defender Charles Bradlaugh, was the battle for the right to affirm. Although the nineteenth century witnessed a shift in allowing Unitarians, Quakers, and Jews the right to make an affirmation, rather than swearing an oath, in a court of law, those professing no religion were denied this right until 1870. In 1854, Truelove’s attempt to give evidence following a theft from his shop was denied, and the case dismissed, when he asked to affirm but was rejected. Asked why he would not swear the oath, Truelove stated: ‘I profess no religion. I claim exemption on conscientious grounds.’ He was informed that objections were valid only on religious, not ‘irreligious’, grounds:

The Quaker was exempted, not because he had no religious belief, but because he had religious scruples which the law deemed it right to respect. No such consideration was shown to the non-believer, and, consequently, if he refused to take the oath his evidence must be rejected.

The thief, George Brooks, who had been charged with stealing a volume of The Lancet, was released. Nevertheless, standing by his position, Truelove refused to take the oath again in 1862.

Edward Truelove died in 1899, in his ninetieth year, retaining ‘his natural force of mind unimpaired.’ His wife Harriett had died aged 84 in January of the previous year. The Trueloves were buried in Highgate Cemetery, like many humanists, where his gravestone inscription reads

Regardless of obloquy, suffering and worldly loss, he battled bravely throughout a long and troubled life to maintain the right of free speech and free thought.

In a graveside address, George Jacob Holyoake lauded Truelove’s lifelong courage and convictions:

If consistency brought peril or loss he never changed. If it brought imprisonment, which it did, he never complained. He did not seek peril – he did not provoke it; and when it came he did not flinch.

As a bookseller and publisher, Truelove’s legacy is one of unselfish loyalty to the causes of free speech, free press, and free thought. As his obituary in the Ethical Record stated, Truelove, and others like him, ‘fought the battle of every writer claiming to express his honest thought’ and ‘made it more difficult for authorities, whether engaged in currying favour with a foreign tyrant or backing up an outworn creed, to coarsely answer the pen with the gaol.’ So too did Truelove live out his values of honesty, reason, and kindness, enriched by those of Owenism, which have shaped humanism today.

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington was an activist, feminist, and humanist, who founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League, and was described by the […]

Those of us who can look back over the last thirty years will not fail to recall Mrs. Lidstone’s friendliness […]

There are in Britain today a great many thoughtful people who have ideals and aspirations that owe nothing to religious […]

The woman artist appears quickly to have grasped the fact that she cannot maintain an isolated and merely selfish point […]