For I am not everlasting, but a human being, a part of the whole as an hour is a part of the day. Like an hour I must come, and like an hour pass away.

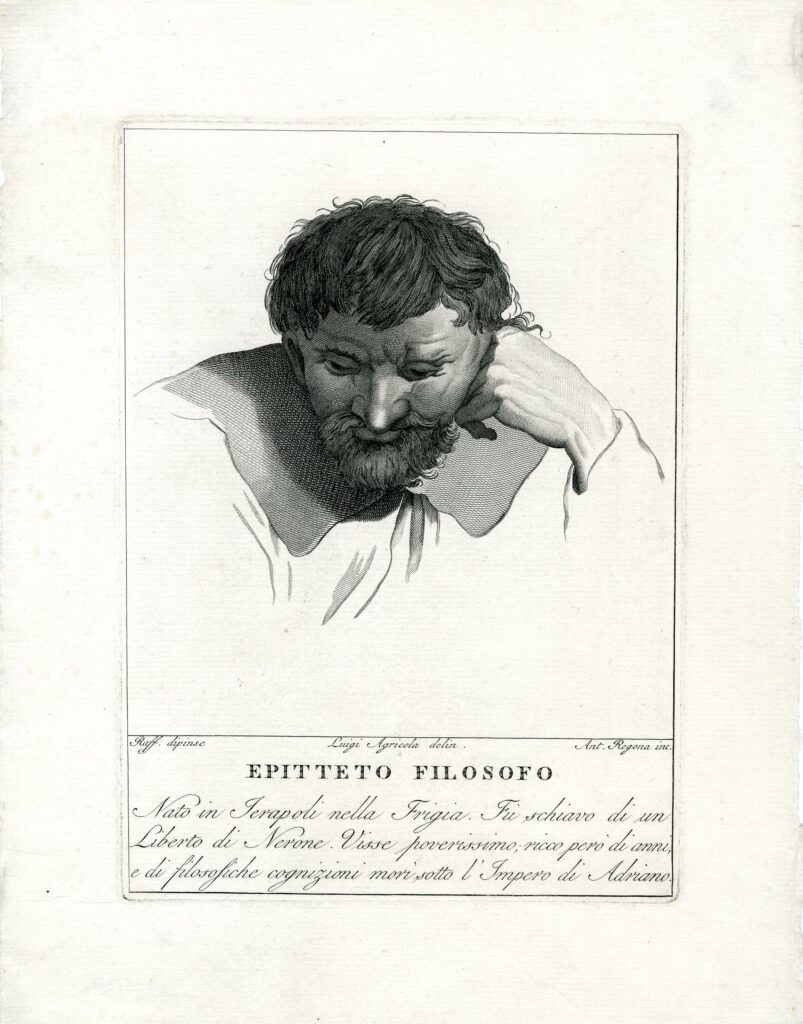

Epictetus was one of the most influential contributors to the Greco-Roman tradition of Stoicism, a tradition of thought with many humanist aspects. His philosophy particularly values the principles of temperance, forgiveness, and respect, believing in human agency, reason, and rational action.

Seek not the good in external things; seek it in yourselves.

Epictetus was born a slave in Hierapolis (now Pamukkale, Turkey) in or around 55 CE. Upon moving to Rome, Epictetus’ master Epaphroditus allowed him to study under the Stoic philosopher and Roman senator Musonius Rufus and, at some point over the following years, Epictetus was freed. Around 89 CE, after all philosophers were banned from Italy by the Emperor Domitian, Epictetus moved to Nicopolis in northern Greece, where he established a school of Stoic philosophy. Whether Epictetus ever put any of this school’s teachings into writing is unknown, but his philosophy was documented by his student Arrian, who wrote two collections of his thought: entitled The Discourses and The Handbook (Enchiridion in Greek).

In The Discourses, Epictetus gives a framework for living a good and ethical life which has three main aspects. The first is to understand and accept the causal nature of the world in order to establish self-dependence in achieving our desires as well as temperance in controlling them. The second is to behave as part of something greater than yourself and treat all humans with dignity and respect; this principle was probably inspired by the humanism that had held sway over many of his Stoic predecessors. Finally, Epictetus placed great importance upon rationality; he suggested that humans, armed with the capacity for rational introspection, are able to determine whether immediate instinctive compulsions are accurate and well-founded (or worthy of assent). As such, assent requires the control of emotion and an avoidance of hasty and illogical reactions to that which lies outside of our power. This idea has become known as ‘the dichotomy of control’ and has since been adopted by many ethicists, as well as being widely implemented in the field of psychology.

Epictetus remained in Nicopolis and continued to teach until his death in 135 CE. In his later years, he had a dysfunctional leg: either the consequence of abuse suffered during his time as a slave, or a defect that he had possessed from birth. Either way, after being born a slave, exiled from his home, and living much of his life with a disability, Epictetus certainly practised the Stoicism that he preached.

Arrian’s books of Epictetus’ thought had a profound and long lasting impact. Stoic philosophy was an important school of thought in the Greco-Roman culture of which Roman Britain was a part. Much later, The Handbook was translated into Latin by the Italian scholar Angelo Poliziano in the fifteenth century and became widely read throughout Europe. Christians reading his work often interpreted it as religious, meaning that it was not necessarily seen as a challenge to the Church. But in fact, Epictetus did not believe in a personal or revelatory god, but one that he took to be immanent and synonymous with ‘Nature’ or ‘the cosmos’: an understanding echoed by some humanists, most notably Spinoza and Einstein.

As Stoicism became better known in Britain from the 18th century onwards, it was an approach adopted by many humanists and is still popular today. Stoicism, particularly the dichotomy of control, has even been adopted in the field of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for treating anxiety and depression. Albert Ellis, the founder of CBT and a lifelong humanist, acknowledged Epictetus as one of his most considerable and enduring influences.

Brooke, C., ‘How the Stoics became Atheists’ in The Historical Journal (2006)

Palmer, A., ‘Humanist Lives of Classical Philosophers and the Idea of Renaissance Secularization’ in Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 70, No. 3., pp. 935-976. (2017)

“Yet, upon the whole, the History of the Decline and Fall seems to have struck root, both at home and […]

Harry Snell was a socialist politician and campaigner, a devoted advocate of the Ethical Movement and a key figure in […]

The National Secular Society is a campaigning organisation, founded in 1866 to champion the principles of secularism and the separation […]

Stanton Coit was a pioneer of the Ethical movement in England and the founder of the West London Ethical Society, […]