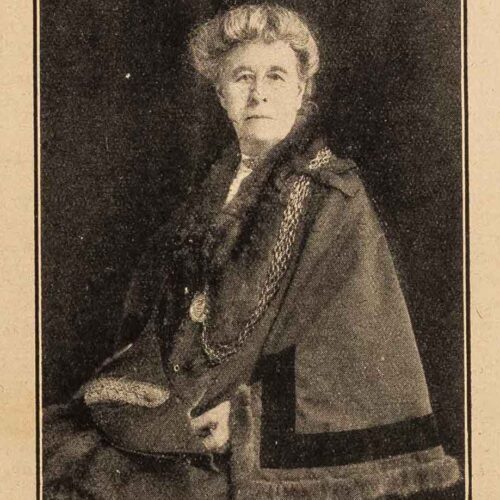

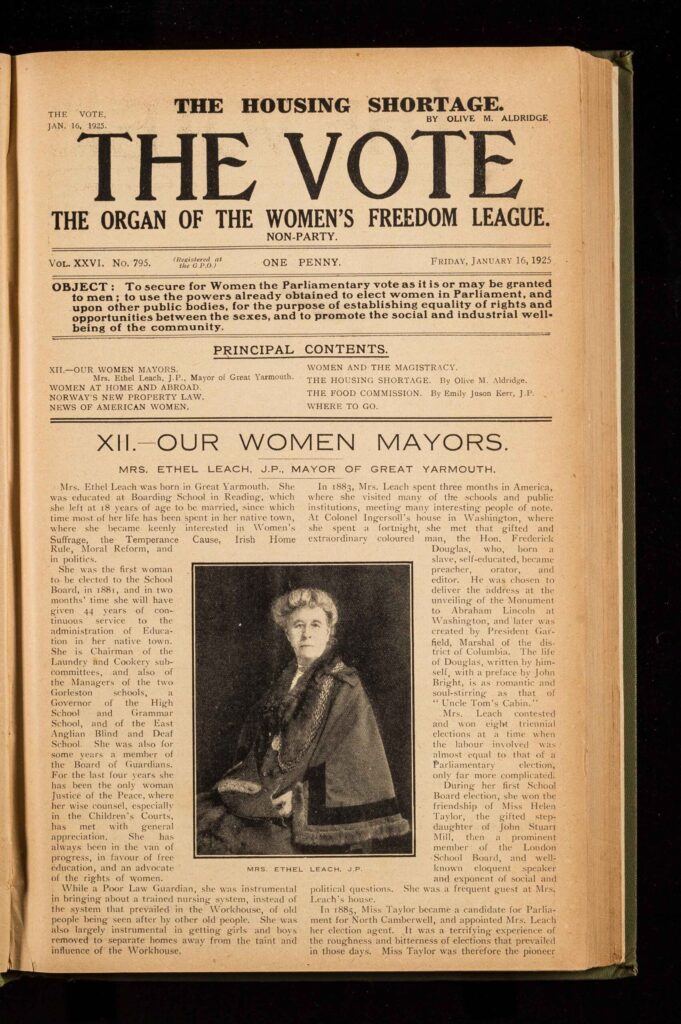

Ethel Leach was a Liberal councillor, social reformer, justice of the peace, and the first female mayor of Great Yarmouth. Active in numerous causes throughout her life, Leach was a close friend of Emilie Holyoake-Marsh, and closely involved in secularist and Fabian circles. In her secularist sympathies, close friendships with other freethinkers, and opposition to the religious and social implications of the 1902 Education Act, Leach ploughed a path familiar to many humanists in the late 19th and early 20th century but, like many of those, has been little remembered by history.

Ethel Leach was born in 1850 in Great Yarmouth to labourer and cartman William Johnson and his wife Mary Ann. At 19 she married John Leach, a local ironmonger and radical, who was a supportive force. From then on she received the greater part of her education, as well as encouragement in pursuing a wide range of social and political causes, including female suffrage, Irish Home Rule, and workhouse reform. John Leach died in 1902 and their only son, Bruce, three years later in 1905.

Leach was elected to the Great Yarmouth School Board in 1881 (the only woman candidate), and became its vice-chair in 1895. In 1894, she was elected to sit on the local Board of Guardians, working to take children out of the workhouse and board them with families. Following her protest against the absence of a trained nurse in the workhouse, one was appointed. As Patricia Hollis has made clear, she was a force to be reckoned with:

Mrs Leach learnt that Yarmouth’s sick wards were headed by a pauper nurse of eighty-one, assisted by another of eighty-five and an inebriate midwife of seventy-one. None of them could read the medicine labels. She introduced trained nurses, tender loving care, and sacked the misogynist clerk to the board, no mean feat as he was a deputy lord-lieutenant of the county, and moved in powerful circles.

In total, Leach spent over four decades working for the improvement of education and social welfare in her hometown, championing the disadvantaged and blazing a trail for other women in local government. She successfully introduced penny dinners and breakfasts for schoolchildren, raised the school leaving age, and – argues Hollis – ‘propelled her board through twenty-five years of educational development in five years’. In seeking to reduce or remove fees in Yarmouth schools, she was accused by church members on the board of doing so ‘not for the sake of the poor but to ruin denominational schools in order to set up a godless education’. Perhaps this provides further indication of Leach’s reputation as a freethinker, as well as a radical.

In 1904, Leach was brought before the court alongside other passive resisters who ‘declined to contribute to the richest church in Christendom to enable teaching to be given which Nonconformists regarded as pernicious.’ The cause of their dissent was the 1902 Education Act, which provided funds for religious instruction in elementary schools, which were mostly owned by Roman Catholics and the Church of England. A nationwide campaign of tax resistance was launched, supported by many Liberals and nonconformists.

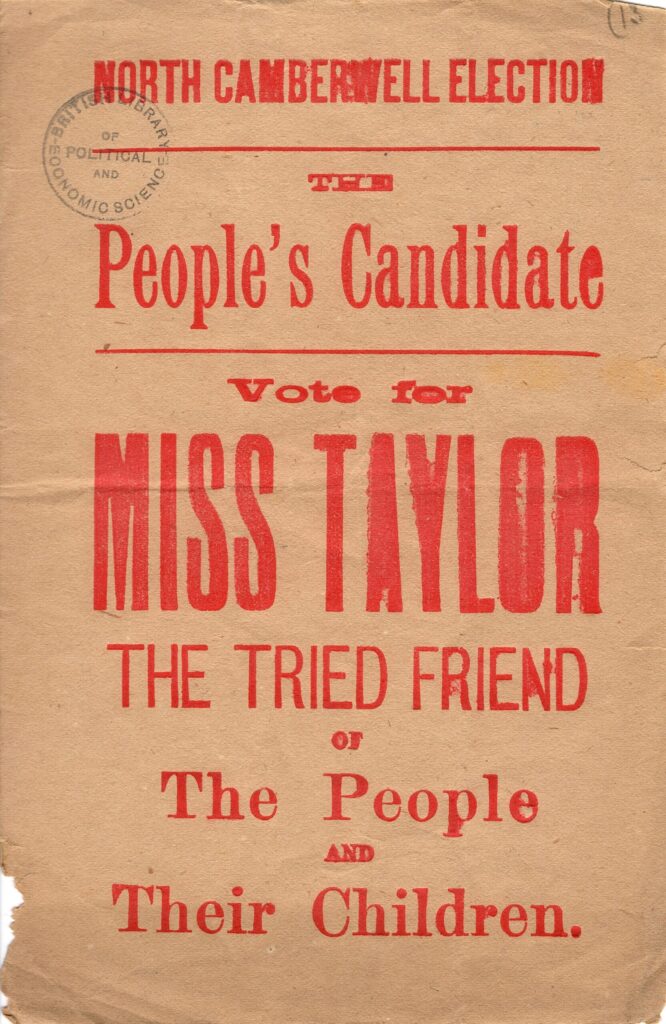

Another extraordinary feature of Leach’s long record in social reform was in 1885, when she was chosen to be Helen Taylor’s election agent in the campaign to become MP for North Camberwell; the first British woman candidate for Parliament (although her papers were refused). Like Emilie Holyoake, with whom Leach had travelled to America two years earlier, Taylor was a feminist and freethinker, the daughter of Harriet Taylor Mill and stepdaughter of John Stuart Mill. Taylor and Leach had become friends during Leach’s first election to the School Board, and shared many common concerns in the realms of reform.

Crowning a decades-long career as a prominent and pioneering figure in local government, in 1920 Ethel Leach became Great Yarmouth’s first female justice of the peace, its first female mayor, and – in 1929 – its first female alderman. As mayor, Leach’s niece and adopted daughter, Hetty, acted as mayoress.

Ethel Leach died on 10 April 1936 in Gorleston.

Following her death, A.M. Perret (the town’s second female Mayor), confirmed Ethel Leach’s role as a pioneer:

In the years now past when ridicule, vulgarity, and criticism were cast upon women who undertook public work, she still went bravely forward, believing that our sex could be of use apart from the domestic life. She fought battles on the old Board of Guardians which were very unpleasant, but her courage and will carried her through. She did her most useful work on the humane side.

As a humane and compassionate social reformer, a pioneering political figure, and a frequent host to radicals and freethinkers, Ethel Leach is an example of one who defended her convictions – and exercised her compassion – to the last. She is also someone whose religious convictions, or lack thereof, have gone unremarked, but her willingness to challenge the power of the Church and fight for reform from a human, rather than divine, standpoint, suggests a distinctly humanist tendency. So too do her close friendships with other prominent humanists of the day.

Is being rewarded for maintaining certain articles as matters of faith, and being punished, or suffering for opposing them, proper […]

What do we live for, if it is not to make life less difficult for each other? George Eliot, Middlemarch […]

The… women on the early ALRA committee were similar in background and outlook. Most of them were active members of […]

What is needed is something in which [we] can all believe irrespective of religion, which in most cases, dare I […]