I have never believed in any formal religion, but I have experienced an emotion that seemed to me religious. In a chapter in Apostate I tried to describe this, but I have been told that I merely described a landscape and a mood, and that the mood had nothing to do with religion. Be this as it may, it was my nearest approach to it…

Forrest Reid, Private Road (1940)

Forrest Reid was a Northern Irish writer, critic, translator, and founding member of the Irish Academy of Letters. Though born into a Protestant family, Reid was a lifelong sceptic of religion, which he wrote openly about about in his two volumes of autobiography: Apostate (1926) and Private Road (1940). One writer for the Northern Whig described Reid as ‘belonging spiritually to the [ancient] Greeks’, whose literature he revelled in, and as a man who instead of any god ‘worshipped every organic thing’. This sense of awe at the natural world, a belief in the inherent value of human relationships, and the rich imaginative capacity expressed in Reid’s works are consummately humanist.

The Belfast Telegraph, in 1954, described Reid’s writing as having ‘a delicate sensitive beauty which suggests that he was a dreamer with the power to express his visionary thoughts’. The Earl of Antrim, opening an exhibition of Reid’s works at Belfast Museum a year earlier, had recalled ‘a gentle rebel who preached the downfall of grossness and inhumanity’. This sense of gentleness and insight recurs in depictions of Reid. His close friend and frequent correspondent, E.M. Forster, wrote to him in 1912:

You are talking – very quietly and beautifully, but talking – about the chasms that surround us. You are describing spiritual scenery, and though you are too skilled a novelist to paint the figures in that landscape as generalities, they are most significant when they remind us that we walk in it too.

E.M. Forster to Forrest Reid, about Reid’s novel Following Darkness, 13 December 1912

The biography reprinted below was first published in October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Allen, Nicholas

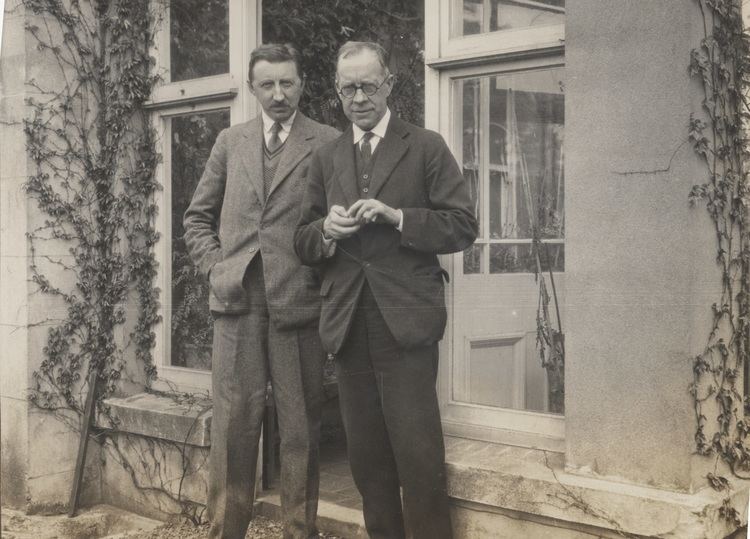

Reid, Forrest (1875–1947), novelist, was born 24 June 1875 at 20 Mount Charles, Belfast, youngest of six surviving children of Robert Reid, manager of Anderson’s Felt Works, and his second wife, Frances Matilda (née Parr), of an aristocratic English family. His family moved to 15 Mount Charles in 1880 but his father died in 1881, leaving the family in genteel poverty. Educated at Miss Hardy’s preparatory school, Belfast, in 1887, he entered the Royal Belfast Academical Institution in 1888, leaving school for a five-year apprenticeship with Musgrave’s tea merchants in 1891. He showed his early experiments in writing to Andrew Rutherford in 1896 before he published his first novel, Kingdom of twilight (1904). Admiring Henry James, he sent the American author a copy of this first work and dedicated the homoerotic The garden god (1905) to him. Scandalised, James stopped all correspondence. Reid entered Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1905, graduating BA in medieval and modern languages in 1908. He returned to live at 9 South Parade, Belfast, and met E. M. Forster, who remained a lifelong friend, in February 1912. In 1914 he moved to 12 Fitzwilliam Avenue, Belfast, before another move to 62 Dublin Road in 1917. His final address was at 13 Ormiston Crescent, Belfast, from 1924. He published consistently: sixteen novels, three critical studies, two volumes of autobiography, and one volume of translated Greek poetry in all. Apostate (1926) is a superb first volume of autobiography, while Peter Waring (1937) captures the sense of dissociation Reid felt from consensus values in his story of a young boy grown to manhood. Male relationships define his work and he lived with Stephen Gilbert, a young writer, from 1931. For all that, his Young Tom (1944), for which he was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction, is stubbornly haut bourgeois, his boy hero dressed for tennis in balmy days subtly charged with erotic atmosphere. But this summer world is capable of eclipse, and a darkness inhabits the shadows of Private road (1940), a second volume of autobiography. A founder member of the Irish Academy of Letters, he was made honorary doctor of literature by QUB in 1933. He died of peritonitis at Warrenpoint, Co. Down, on 4 January 1947. He is buried in Dundonald cemetery and a plaque marks his last home. Two portraits of him survive: one by Arthur Greeves (friend of C. S. Lewis (qv)), in possession of the Royal Belfast Academical Institution, and one by James Sleator (qv), in possession of the Ulster Museum.

Northern Whig, Belfast News Letter, 6 Jan. 1947; John Boyd, ‘Forest Reid: an introduction to his work’, Irish Writing, no. 4 (Apr. 1948), 72–7; John Boyd, ‘Ulster prose’, Sam Hanna Bell, Nesca Robb, and John Hewitt (ed.), The arts in Ulster: a symposium (1951), 99–130; Russell Burlingham, Forrest Reid: a portrait and a study (1953); J. W. Foster, Forces and themes in Ulster fiction (1974); Threshold, xxviii (spring 1977); George Buchanan, ‘An Irish pastoral’, Honest Ulsterman, lvi (May–Sept. 1977), 132–3; Brian Taylor, ‘A strangely familiar scene: a note on landscape and locality in Forrest Reid’, Irish University Review, vii, no. 2 (autumn 1977), 213–18; Brian Taylor, The green avenue: the life and writings of Forrest Reid, 1875–1947 (1980); E. M. Forster, Two cheers for democracy (1972 ed.); Damian Smyth (ed.), ‘Lost fields’, supplement to Fortnight, no. 306 (May 1992); E. M. Forster, Abinger harvest (1996 ed.; ed. by Elizabeth Heine); Éibhear Walshe (ed.), Sex, nation and dissent in Irish writing (1997); Paul Goodman and Brian Taylor (ed.), Retrospective adventures (1998); Gillian McIntosh, The force of culture (1999)

Forrest Reid | Dictionary of Irish Biography and Dictionary of Ulster Biography

Forrest Reid | Find a Grave

I have been the more bold in exposing my opinion because I believe it to be the dictates of truth […]

It is not to the point to say that the views of Lucretius and Bruno, of Darwin and Spencer, may […]

The obituary reproduced below was written by George Broadhead, and originally appeared in a 1997 issue of The Gay Humanist […]

Those of us who can look back over the last thirty years will not fail to recall Mrs. Lidstone’s friendliness […]