I have devoted my time and fortune to laying the foundation of a society where affection shall form the only marriage, kind feelings and kind action the only religion, respect for the feelings and liberties of others the only restraint, and union of interest the bond of peace and security.

Frances Wright

Frances Wright was an abolitionist, feminist, freethinker, and social reformer. Born in Scotland, Wright was transfixed from an early age by the egalitarian promise of America, but later disappointed by its hypocrisy in upholding the institution of slavery. Motivated by humanist values of reason, compassion, and freedom, entirely loosed from any concept of gods, Wright became a lifelong champion of women’s rights, equality, and freedom of belief, and a major influence on many who came after her.

Frances Wright was born on 6 December 1795 in Dundee. She was the daughter of Camilla Campbell and James Wright, a wealthy and liberal-minded linen merchant who had promoted the works of Thomas Paine and French political radicals. But before she was three years old, Wright and her two siblings were orphans, and raised in London by a series of relatives of a much more conservative persuasion.

Wright’s brother died aged 15, and at 21 Frances and her sister Camilla went to live with a great-uncle in Glasgow. Here, she read voraciously, socialised widely, and conceived an admiration for the United States of America, the ‘new world’ she felt embodied liberal values missing from England at the time. This led, in 1818, to her first trip to America, where she stayed for two years, meeting, among many others, Thomas Jefferson. On her return to England, she published Views of Society and Manners in America.

Wright returned to America in 1824, following several years in England and France and close friendships with Jeremy Bentham and the Marquis de La Fayette. Focusing ever more on the injustices of slavery, she began to develop a plan for demonstrating the means of emancipation. At the end of 1825, Wright purchased a tract of land in Tennessee, which she named Nashoba: the Chickasaw word for ‘wolf’. She also ‘bought’ several families of enslaved people, and set about a five-year scheme over the course of which they would work to secure their freedom, while receiving an education. Wright had been inspired by a visit to Robert Owen’s community at New Harmony, and similarly sought to prove that character was shaped by environment and opportunity, not fixed from birth.

Inadequate land, lack of financial resources, and the disinterest of southern planters all contributed to the eventual failure of the community at Nashoba. The harsh conditions also affected Wright’s health, prompting her to return to Europe in 1827, leaving Nashoba in the hands of others. In 1830, she took the 18 adults and 16 children to Haiti, where she gave them their freedom. From then on, Wright’s focus was on lecturing and writing, as well as on editing the Free Enquirer, a journal devoted ‘to free, unbiased, and universal inquiry’.

In writing and speaking, Wright’s focuses were the subjugation of women, the corrupting influence of wealth, the evils of organised religion, and the shame of slavery. Though most of her suggested solutions were too extreme or impractical to be implemented, her ideas – and her boldness in expressing them – were an influence on many writers, feminists, and reformers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Mary Shelley.

Frances Wright died in Cincinatti on 13 December 1852, aged 57. Her gravestone, in Spring Grove cemetery, read in part:

Human kind is but one family; the

education of its youth should be equal and

universal.

I believe in Frances Wright, as a true, self-sacrificing soul, of whom the Freethinkers of all countries should be proud.

Sara A. Underwood in Heroines of Freethought (1876)

Despite the failure of her practical efforts towards reform, Frances Wright championed many social causes years before they were addressed or remedied more widely. Wright was driven by a desire for change, informed not by any belief in divine external forces, but by her own sense of reason, compassion, and humanity. Many freethinkers followed in her wake, and many took up her arguments about the damage wrought by organised religion, particularly on the rights of women in work, marriage, and childbearing. In this, she blazed a trail for all of the humanists who came after her, seeking social improvement for all in the one life we have.

Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]

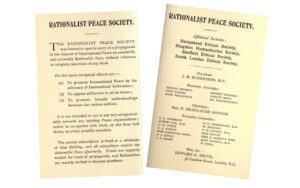

…a slowly growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war… is not in consequence of any […]

About the moral problem there is nothing mysterious; it is simply the old, old question of how best to live […]