The educative work and the profound enlightenment resulting from the publication of the cheap RPA reprints and the Thinker’s Library found their inception in the work which Fred Watts and his father undertook in a cause to which they devoted their lives.

Joseph Reeves on F.C.C. Watts in The Literary Guide, December 1953

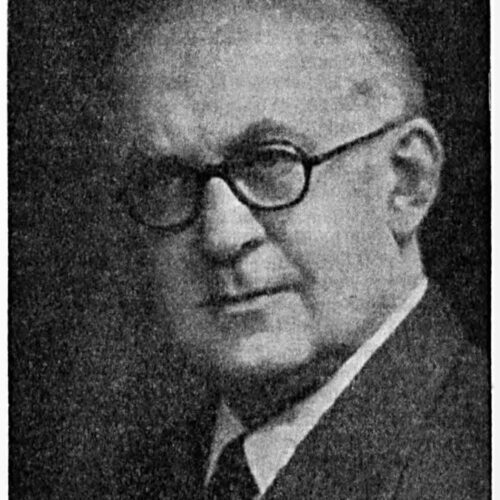

Frederick Charles Chater Watts was the son of Rationalist Press Association founder Charles Albert Watts, whose publishing legacy he continued. Among his major contributions was the introduction of the Thinker’s Library series, which ran from 1929 until 1951, bringing key humanist and scientific texts to a wide audience. As C. Bradlaugh Bonner wrote in his Literary Guide obituary (reproduced below), it was largely thanks to this that by his death in 1953 rationalist publications were finding a larger audience—and meeting far less resistance—than they had half a century before.

From: The Literary Guide, December 1953

By C. BRADLAUGH BONNER

Frederick was born on March 1, 1896, at a time when his father was working his way towards the foundation of the Rationalist Press Association Ltd. by way of The Rationalist Press Committee.

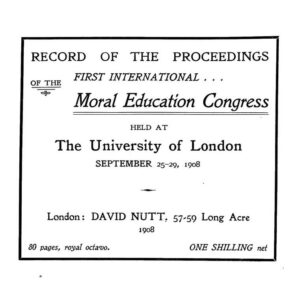

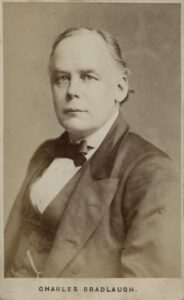

WHEN in 1856 John Watts and Charles Bradlaugh began work together on Half-Hours with Eminent Freethinkers and went to Austin Holyoake to print it, there was initiated a family élan which has endured for the three generations. John died at the early age of thirty-two and was replaced by his brother Charles, who was already his lieutenant; and when Austin Holyoake died, the son of Charles, by name Charles Albert, who had been apprenticed to Austin Holyoake, took over the printing and publishing business at 17 Johnson’s Court. While his father was in Canada, Charles Albert, after one or two fruitless trials, published The Literary Guide (A Record of Liberal and Advanced Publications) and later in the same year The Agnostic (now Rationalist) Annual. These two publications, though not necessarily remunerative in themselves, have been the great means through which Charles Albert and later his son Frederick extended and maintained their influence among readers of progressive views.

Frederick was born on March 1, 1896, at a time when his father was working his way towards the foundation of the Rationalist Press Association Ltd. by way of The Rationalist Press Committee; so Fred grew up with the Association and in the atmosphere of the Sixpenny Reprints. He was educated at Highgate School, one at that time with a somewhat clerical and games atmosphere which he did not find over congenial. Still he left it with a good and well-merited reputation and some distinction as a gymnast. It was an abrupt step from such a school to Johnson’s Court, and then into the Army for the First World War. But Fred was of tough material and returned from the battlefields of France full of vigour, ideas, and willingness to help his father in the testing years after the war. The Sixpenny Reprints, one of the most remarkable feats of publishing in the first decade of our century, had exhausted the impulse which had borne them to success; they could no longer be marketed at 6d. The market was becoming steadily worse as the country moved towards the great crisis of the early 1930s. Fred, already his father’s mainstay and a director of the RPA since 1921, now proposed the Thinker’s Library, which was launched in 1929 at 1s a volume. Each year there was a steady and marked rise in sales; with it the RPA’s membership increased. In 1930 Charles Albert retired, handing over to his son the reins. In a few years it was apparent that the Thinker’s Library was as great a success as the Sixpenny Reprints. Fred’s genius was taking the ‘‘Thinker’s” into regions almost untapped by Freethought publishers and was breaking down the opposition of booksellers fearful for their sales among the conventionally correct. The shadow of a new war slowed down sales and reduced membership numbers, but when the Second World War came it had the result, unforeseen by those who judged the probable condition in the light of the first war, of sending up sales and increasing membership until 1946, when they began tailing off.

The influence of father and son through the medium of the Reprints and of the Thinker’s Library on contemporary culture has been immense.

The influence of father and son through the medium of the Reprints and of the Thinker’s Library on contemporary culture has been immense. Its measure can be taken from the pages of that report on evangelism, Towards the Conversion of England, published by the Church of England, where it is recommended (p. 111) that text-books on secular subjects should be published and impregnated with the Christian faith of the writers ‘‘in the same way as does the agnosticism of the writers of such books as those published in the Thinker’s Library.”’

Whereas before 1914 it was difficult to persuade booksellers to display Watts’s books, today such displays are not infrequent and trade opposition on religious grounds is fading. For this success Fred Watts’s management of the Thinker’s Library is largely responsible.

Everyone had to be up to his job, and managing-director Fred could be a real tartar. On the other hand he was a human, friendly person who took thought for all who worked with him and yet withal was a realist.

Fred was brought up in the school of long hours for modest pay, and he expected his staff to give as good, or nearly, as he gave himself. Everyone had to be up to his job, and managing-director Fred could be a real tartar. On the other hand he was a human, friendly person who took thought for all who worked with him and yet withal was a realist. Initiative and drive lose much of their resultant force without order, and Fred was methodical.

It was most unfortunate that, just at the time when the war-time boom in bookselling had exhausted its momentum, Fred should have been the victim of a stroke. There were many with the goodwill to help him at Johnson’s Court, but no one with his experience, mastery, and powers. To be kept in bed or at home when the business outlook was growing darker and darker was a torment for him. Perhaps, when matters were going well, he saw the future all couleur de rose; perhaps as the tide turned, he was over-gloomy; but he ever endeavoured to “get down to brass tacks,” and to move with caution, making sure of his ground first. Those days when he was ill and worried were unhappy ones for him.

Perhaps, when matters were going well, he saw the future all couleur de rose; perhaps as the tide turned, he was over-gloomy; but he ever endeavoured to “get down to brass tacks”…

Fred had known bitter hours; his sister Sally died early; his mother, too, after a trying illness. The hardest blow was when his elder daughter Doreen developed the same diabetic symptoms as Sally but, thanks to insulin, lived till the day after Christmas 1948, dying when her father was still very ill.

Strength returned gradually, but Fred felt that his working days were numbered and he wished, before he dropped out, to put everything in order for those who should succeed him.

With this end in view, in the accomplishment of his father’s wishes, he transferred the family holdings in C. A. Watts & Co Ltd to the RPA. This was made easier since Mrs Dixon, his sister, after long, devoted, and unassumingly efficient service to the family and to the Cause, was about to retire; but it was performed only by means of negotiations lasting nearly two years—a great strain on a sick man—and it was followed by a year of constructive planning to meet the new set of circumstances.

In the meantime the “Thrift” series was launched at 1s a volume, intended to take the place of the Thinker’s Library, just as the Thinker’s Library had replaced the Sixpenny Reprints, but the market was not so favourable and the series was to Fred a further source of strain and discouragement.

Fred lived a good life. Many at Johnson’s Court have served long years, several all their working lives, under him and his father, and bore him a deep affection.

And now, as the planning was coming to an end, as the future seemed more hopeful, Fred has died. He has left everything in order as far as it was possible for him, both in his business and his private affairs, so thoughtful was he of others. He was most fortunate in his wife, who always supported him wherever she could, a tower of strength in the dark days and a steadying influence at all times; and he was happy and proud to have the efficient help of his daughter, Marion, and to see how with a firm hand she could deal with difficulties.

Fred lived a good life. Many at Johnson’s Court have served long years, several all their working lives, under him and his father, and bore him a deep affection. Business acquaintances knew him as one who could drive a hard bargain, but also as one they could respect and admire. He was an approachable, generous being, whom I, for one, miss deeply.

By PROF A. E. HEATH

(President of the Rationalist Press Association)

To me, the memory of Fred Watts is not one of struggle. When I first met him he gave a sense of easy genial effectiveness. There was a happy friendliness which made our Board and Johnson’s Court more like a home than a place of business.

Professor A.E. Heath

Courage is continued action under jeopardy. Fred Watts felt to the end that he was obliged to carry on, even at grave personal risk, in order to fulfil the filial obligations he owed to the work of his father and grandfather. He wanted to leave, when leave it he must, their great tradition of service to Rationalism unsullied.

Yet, to me, the memory of Fred Watts is not one of struggle. When I first met him he gave a sense of easy genial effectiveness. There was a happy friendliness which made our Board and Johnson’s Court more like a home than a place of business.

Death is such a finality. It will take us a long time to realize how much we shall miss his smiling greeting, his advice and his encouragement. Our loss must be less keen than his family’s, but they, I am sure, will feel with us the force of Sam Butler’s epitaph:

I fall asleep in the full and certain hope

Samuel Butler, Erewhon Revisited (1901)

That my slumber shall not be broken;

And that though I be all-forgetting,

Yet shall I not be all-forgotten,

But continue that life in the thoughts and deeds

Of those I loved,

Into which, while the power to strive was yet

vouchsafed me,

I fondly strove to enter.

By JOSEPH REEVES, MP

I would like to say to those who mourn the passing of a dear friend and a devoted Rationalist that the way such proper sentiments can be most adequately expressed is by sustained and increased contributions over the whole field of Rationalist thought and action to the things for which Fred Watts stood.

Joseph Reeves, M.P.

The death of Fred Watts removes a symbolic figure from the ranks of Rationalism at a moment when the Movement needs his qualities most. The name of Watts and Rationalism are almost synonymous both in Britain and abroad and no modern progressive thinker can recall the history of scientific advancement during this and the last century without the name of Watts rushing to his or her mind. The educative work and the profound enlightenment resulting from the publication of the cheap RPA reprints and the Thinker’s Library found their inception in the work which Fred Watts and his father undertook in a cause to which they devoted their lives.

As Chairman of the Rationalist Press Association Ltd, I would like to say to those who mourn the passing of a dear friend and a devoted Rationalist that the way such proper sentiments can be most adequately expressed is by sustained and increased contributions over the whole field of Rationalist thought and action to the things for which Fred Watts stood.

Our Movement is passing into a period in which man is haltingly making readjustments to the great changes which the scientific progress of the past has brought in its train. Our Movement has made no small contribution to the popularization of the scientific approach to all problems of life. It is therefore not for us of all people to shrink from the logic of the great social problems of the new world we are inheriting. But it does mean facing the realities of life as it is and our friend, with his links with the past and his vision of the future, would have us play the part today which the pioneers of the past played in elevating reason to the highest place in the affairs of man.

By SIR ARTHUR KEITH

Charles Watts kept us together by his manifest honesty of purpose, by his spirit of tolerance and understanding and his ever-present flow of goodwill.

Sir Arthur Keith

Seven years ago, when I saw Frederick Watts shoulder the heavy burden just laid down by his father, I own, as I am now free to confess, that he would find the burden rather beyond his strength. It well may be thought that men and women who claim to be led by reason are easy people to manage, but, as a matter of fact, it is just such men and women who are given a more than usual share of an independency of mind and a love of individual liberty—qualities which make leadership particularly difficult. There is among us that exploratory urge which tends to carry us in diverse directions. Charles Watts kept us together by his manifest honesty of purpose, by his spirit of tolerance and understanding and his ever-present flow of goodwill. Some of these gifts were never patently manifest in Frederick Watts; he gave the impression, in those earlier days, of looking at life with the eyes of a businessman, keeping in strict reserve his personal outlook on the more intimate problems of life. My fears were groundless; he succeeded, and his success was due in the main to his honesty in word and deed and to his sound judgment, and also because, like his father, he was content to remain in the background and leave the planning to the more active brains of the RPA. May we find some one fit to succeed him is my earnest wish.

By J. HUTTON HYND

We have lost a very good and a very gracious friend.

J. Hutton Hynd

We have lost a very good and a very gracious friend. We can say sincerely that on our first meeting with Mr Watts we were aware of a warm intimacy and fellowship of mind and spirit—a truly cordial and deeply sincere fellow-feeling, which deepened as time went on. I was always particularly reassured and pleased on attending meetings of the RPA to see Mr Watts present: and there was an awareness of his personal integrity, his balanced good judgment and good sense. Mr Watts carried forward and extended the truly great tradition of publishing in a specialized field as set up by his father—and this in a time of great difficulty and distress.

By EDEN PHILLPOTTS

It is indeed a radical loss that the death of Mr Watts brings to our Association and to many of its members who enjoyed the personal privilege of his friendship. It is my sorrow to know this great man is no more.

I was not, and was conceived. I loved and did a little work. I am not and grieve not. Epitaph […]

We must grow out of the crude and unreal ideas of immortality and content ourselves with the only kind of […]

To have thus assuaged the temper of controversy, to have softened much deep-seated prejudice and to have disposed some of […]

Charles Bradlaugh was a leading freethinker, secularist, and founder of the National Secular Society. His efforts to take his seat […]