The reward of a useful and virtuous life is the conviction that our memory will be cherished by those who come after us, as we revere the memories of the great and good who have gone before. This is the only immortality of which we know…

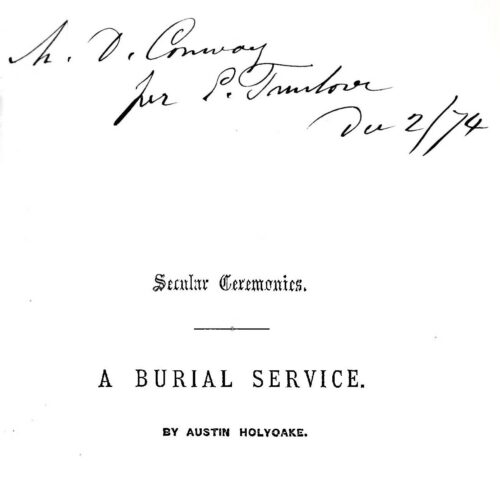

This secular burial service was written by the printer and publisher Austin Holyoake (1826–1874). His brother, George Jacob Holyoake, coined the term ‘secularism‘ in 1851 to describe a philosophy synonymous with humanism today: focused on living happy, moral, and useful lives without reference to supernatural ideas or concepts of an afterlife. Austin Holyoake’s secular service was widely used by non-religious people for decades to come, including at his own funeral. In its emphasis on honouring the beliefs of the deceased, and encouraging personalisation, Holyoake’s burial service is a clear precursor of today’s humanist funeral ceremonies.

Printed as part of the Secularist’s Manual of Songs and Ceremonies (1871), this burial service was also produced as a standalone pamphlet, digitised by Conway Hall. It can be read in its original form, alongside hundreds of other 19th century pamphlets, in Conway Hall’s digital collections.

The following is designed as one of the services for the little Manual of Secular Ceremonies. Having lost the nearest and dearest relatives a man can know—having passed, I may say, through a baptism of bereavement, I know but too well the agony of the grave side. I have endeavoured—but very inadequately, I am sure—to produce a short service which shall afford consolation and reconcilement to the sorrowing, from a Secular point of view. The service as it now stands is suitable to be said over the grave of an adult male; it may, with slight effort, by altering the gender, be made suitable for a female also. It is almost impossible to write that which would be applicable to all persons of all ages. It can always be sufficiently individualised by some friend of the deceased introducing a few remarks of a personal nature.

We this day consign to the earth the body of our departed friend; for him life’s fitful dream is over, with its toils, and sufferings, and disappointments. He derived his being from the bountiful mother of all; he returns to her capacious bosom, to again mingle with the elements. He basked in life’s sunshine for his allotted time, and has passed into the shadow of death, where sorrow and pain are unknown. Nobly he performed life’s duties on the stage of earth; the impenetrable curtain of futurity has fallen, and we see him no more. But he leaves to his sorrowing relatives and friends a legacy in the remembrance of his virtues, his services, his honour, and truth.

His religion was of this world—the service of humanity his highest aspiration. He recognised no authority but that of Nature; adopted no methods but those of science and philosophy; and respected in practice no rule but that of conscience, illustrated by the common sense of mankind.

He fought the good fight of Free Inquiry, and triumphed over prejudice and the results of misdirected education. His voyage through life was not always on tranquil seas, but his strong judgment steered him clear of the rocks and quicksands of ignorance, and for years he rested placidly in the haven of self- knowledge. He had long been free from the fears and misgivings of superstitious belief. He worked out for himself the problem of life, and no man was the keeper of his conscience. His religion was of this world—the service of humanity his highest aspiration. He recognised no authority but that of Nature; adopted no methods but those of science and philosophy; and respected in practice no rule but that of conscience, illustrated by the common sense of mankind. He valued the lessons of the past, but disowned tradition as a ground of belief, whether miracles and supernaturalism be claimed or not claimed on its side. No sacred Scripture or ancient Church formed the basis of his faith.

…his independent method of thought tended to develop those sentiments which have their source in human nature—which impel and ennoble all morality—which are grounded upon intelligent personal conviction…

By his example, he vindicated the right to think and to act upon conscientious conviction. By a career so noble, who shall say that his domestic affections were impaired, or that his love for those near and dear to him was weakened? On the contrary, his independent method of thought tended to develop those sentiments which have their source in human nature—which impel and ennoble all morality—which are grounded upon intelligent personal conviction, and which manifest themselves in worthy and heroic actions, especially in the promotion of Truth, Justice, and Love. For worship of the unknown, he substituted Duty; for prayer, Work; and the record of his life bears testimony to his purity of heart; and the bereaved ones know but too well the treasure that is lost to them for ever. If perfect reliance upon any particular belief in the hour of death were any proof of its truth, then in the death of our friend the principles of Secularism would be triumphantly established. His belief sustained him in health; during his illness, with the certainty of death before him at no distant period, it afforded him consolation and encouragement; and in the last solemn moments of his life, when he was gazing as it were into his own grave, it procured him the most perfect tranquillity of mind. There were no misgivings, no doubts, no tremblings lest he should have missed the right path; but he went undaunted into the land of the great departed, into the silent land. It may be truly said of him, that nothing in life became him more than the manner of his leaving it.

Death is but the shadow of a shade, and there is nothing in the name that should blanch the cheek or inspire the timid with fear. In its presence, pain and care give place to rest and peace.

Death has no terrors for the enlightened; it may bring regrets at the thought of leaving those we hold dearest on earth, but the consciousness of a well-spent life is all-sufficient in the last sad hour of humanity. Death is but the shadow of a shade, and there is nothing in the name that should blanch the cheek or inspire the timid with fear. In its presence, pain and care give place to rest and peace. The sorrow-laden and the forlorn, the unfortunate and the despairing, find repose in the tomb—all the woes and ills of life are swallowed up in death. The atoms of this earth once were living man, and in dying, we do but return to our kindred who have existed through myriads of generations.

[Here introduce any personal matters relating to the deceased.]

Now our departed brother has been removed, death, like a mirror, shows us his true reflex. We see his character undistorted by the passions, the prejudices, and the infirmities of life. And how poor seem all the petty ambitions which are wont to sway mankind, and how small the advantages of revenge. Death is so genuine a fact, that it excludes falsehood, or betrays its emptiness; it is a touchstone that proves the gold, and dishonours the baser metal. Our friend has entered upon that eternal rest, that happy ease, which is the heritage of all. The sorrow and grief of those who remain, alone mar the thought that the tranquil sleep of death has succeeded that fever of the brain called living. Death comes as the soothing anodyne to all our woes and struggles, and we inherit the earth as a reward for the toils of life.

Every form that lives must die, for the penalty of life is death…. There is not a flower that scents the mountain or the plain, there is not a rose-bud that opes its perfumed lips to the morning sun, but, ere evening comes, may perish.

The pain of parting is poignant, and cannot for a time be subdued; but regrets are vain. Every form that lives must die, for the penalty of life is death. No power can break the stern decree that all on earth must part; though the chain be weaved by affection or kindred, the beloved ones who weep for us will only for a while remain. There is not a flower that scents the mountain or the plain, there is not a rose-bud that opes its perfumed lips to the morning sun, but, ere evening comes, may perish. Man springs up like the tree: at first the tender plant, he puts forth buds of promise, then blossoms for a time, and gradually decays and passes away. His hopes, like the countless leaves of the forest, may wither and be blown about by the adverse winds of fate, but his efforts, springing from the fruitful soil of wise endeavour, will fructify the earth, from which will rise a blooming harvest of happy results to mankind.

In the solemn presence of death… our obvious duty is to emulate the good deeds of the departed, and to resolve so to shape our course through life, that when our hour comes we can say… we never wilfully did a bad act, never deliberately injured our fellow-man.

In the solemn presence of death—solemn, because a mystery which no living being has penetrated— on the brink of that bourne from whence no traveller returns, our obvious duty is to emulate the good deeds of the departed, and to resolve so to shape our course through life, that when our hour comes we can say, that though our temptations were great—though our education was defective—though our toils and privations were sore—we never wilfully did a bad act, never deliberately injured our fellow-man. The reward of a useful and virtuous life is the conviction that our memory will be cherished by those who come after us, as we revere the memories of the great and good who have gone before. This is the only immortality of which we know—the immortality of the great ones of the world, who have benefitted their age and race by their noble deeds, their brilliant thoughts, their burning words. Their example is ever with us, and their influence hovers round the haunts of men, and stimulates to the highest and happiest daring.

Man has a heaven too, but not that dreamed of by some—far, far away, beyond the clouds ; but here on earth, created by the fireside, and built up of the love and respect of kindred and friends, and within the reach of the humblest who work for the good of others and the perfectibility of humanity.

Man has a heaven too, but not that dreamed of by some—far, far away, beyond the clouds ; but here on earth, created by the fireside, and built up of the love and respect of kindred and friends, and within the reach of the humblest who work for the good of others and the perfectibility of humanity. As we drop the tear of sympathy at the grave now about to close over the once loved form, may the earth lie lightly on him, may the flowers bloom o’er his head, and may the winds sigh softly as they herald the coming night. Peace and respect be with his memory. Farewell, a long farewell!

LONDON:

AUSTIN & Co., 17, JOHNSON’S COURT, FLEET STREET, E.C.

PRICE ONE PENNY.

Bessie Braddock was a trade union activist and politician, who devoted her life to improving the lives of others. She […]

To accept life fully seems to me the hallmark of the fine spirit. I think that it is possible for […]

The tremendous influence of Moore and his book on us came from the fact that they suddenly removed from our […]

Charles Albert Watts was a lifelong promoter of rationalism, and the founder in 1885 of Watts’s Literary Guide, still published […]