The death of Shaw is to progressive people of the twentieth century what the death of Voltaire must have been to those of the eighteenth. No one else so completely summed up in his own personality the forces which transformed the intellectual atmosphere of his age.

Archibald Robertson, ‘George Bernard Shaw’ in The Literary Guide, December 1950

Irish writer and activist George Bernard Shaw died on 2 November 1950. The contemporary recollections below, printed in The Literary Guide (now New Humanist), show his influence on the thinking of his time, as well as some of his interactions with the humanist and rationalist movements of the late 19th and early 20th century.

The Literary Guide, December 1950

By ARCHIBALD ROBERTSON

THE death of Shaw is to progressive people of the twentieth century what the death of Voltaire must have been to those of the eighteenth. No one else so completely summed up in his own personality the forces which transformed the intellectual atmosphere of his age.

I had become a Rationalist and then a Socialist quite independently of him. But he found words, winged words, barbed words, stinging words, for much that I felt in a fumbling way and liked to see plainly in print.

I first heard of Shaw in my school-days, before reading a word of his writings or seeing any of his plays. I knew of him as a Fabian and therefore a Socialist, but as one who, unlike most Socialists, had made such a name in his chosen profession as to be, even in those days, “news” to the Press. In 1905 I went to Oxford, joined the Fabian Society, and began to read him. Here was a new joy in life. Not that Shaw taught me very much that was new. I had become a Rationalist and then a Socialist quite independently of him. But he found words, winged words, barbed words, stinging words, for much that I felt in a fumbling way and liked to see plainly in print. Like all men of genius, he voiced clearly the unclear thoughts of millions, of whom I was one.

Shaw never called himself a Rationalist, but he nevertheless did a Rationalist’s work. The first explicit statement of his philosophy, The Quintessence of Ibsenism, is ostensibly an attack on Rationalism. But the Rationalism which he attacks is an Aunt Sally set up in order to be knocked down. Shaw’s Rationalist, who goes about “acting logically with the object of securing the greatest good of the greatest number” and practises “syllogism worship with rites of human sacrifice,” never lived or will live. To Rationalism in the concrete, as embodied in Voltaire, Paine, and Bradlaugh, Shaw was always well disposed, knowing as he did very well that he stood on their shoulders.

If a Rationalist is one who uses reason as it should be used—namely, as a tool with which to demolish beliefs and institutions that hamper human life—our age and country have seen no greater Rationalist than Shaw.

If a Rationalist is one who uses reason as it should be used—namely, as a tool with which to demolish beliefs and institutions that hamper human life—our age and country have seen no greater Rationalist than Shaw. The early work quoted, while attacking something that Shaw labels Rationalism, riddles with more effective mockery the “pious man” who thinks that disbelievers in the Bible lead evil lives and end screaming on their deathbeds. It is the same in the plays. Shaw’s sharpest arrows, like Voltaire’s, are aimed at those who behind the mask of orthodoxy and respectability defend iniquity. “Oh, if I only had my life to live over again!” exclaims Mrs. Warren. “I’d talk to that lying clergyman in the school”—meaning the clergyman who taught her as a girl that it was better to work fourteen hours a day for four shillings a week than “sin.” So with later plays—The Devil’s Disciple, Major Barbara, and so on. Even in Saint Joan the emphasis is on the heresy of the Maid—though some of us may think that here Shaw’s anxiety to be fair to her persecutors, too, leads him to do them more than justice.

By middle age Shaw had achieved a position of leadership among those who delighted to see educated ignorance exposed and solemn humbug smitten.

By middle age Shaw had achieved a position of leadership among those who delighted to see educated ignorance exposed and solemn humbug smitten. Then in 1914 came what his enemies rejoiced to think was an irreparable débacle. In Common Sense About the War Shaw actually dared to criticize British foreign policy at a time when it was a patriotic duty to equate “British” with “ white” and “German” with “black.” The word went round that Shaw was a pro-German. He was nothing of the sort. What he had done was to adopt the astute dialectical device of first making every possible point against Grey’s policy and then arguing that nevertheless every friend of mankind must work for the defeat of the greater evil, German militarism. As, rightly or wrongly, that was what I thought at the time, I found Shaw’s pamphlet timely and helpful. But those who abused him seldom read him. Their abuse was a biting satire on themselves.

Then followed Shaw’s remarkable come-back after 1918. Slowly and surely he ripened into a national institution. I do not think any of his later plays were quite up to his early level. They seemed to become more and more remote from life and to tail off in the end into brilliant, academic dialogues. But for the masterpieces of the early Shaw, for Mrs. Warren, Candida, Man and Superman, The Doctor’s Dilemma, and the rest, we owe him thanks, honour, and remembrance.

By C. BRADLAUGH BONNER

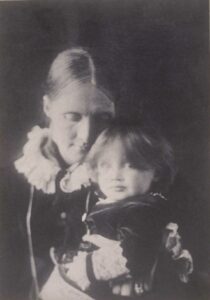

FIFTEEN years ago, when my mother died, Shaw wrote to me: “I had a special regard for Hypatia… she was so simple and sincere… her memory is altogether pleasant; and death, at my age, means nothing.” He was born two years before my mother, and now, for Time’s moving hand cannot be stilled, he too is dead.

My father used to join in boxing on the lawn with Shaw, Hubert Bland, and J. M. Robertson. The picture thus evoked is highly comic, for they were of widely assorted sizes and differing skills.

In the later ’80s Mrs. Besant rented a house in Avenue Road, St. John’s Wood. My parents dwelt for a time in the top flat, and in the drawing room foregathered the proto-Fabians and others with whom my parents were generally on good terms. My father used to join in boxing on the lawn with Shaw, Hubert Bland, and J. M. Robertson. The picture thus evoked is highly comic, for they were of widely assorted sizes and differing skills. The author of Cashel Byron, who was then writing for Our Corner, Mrs. Besant’s periodical, no doubt drew inspiration from such encounters; Bruin, Mrs. Besant’s big dog, certainly did. There was also much music, or talk of music. Shaw was then gaining a living as “Corno di Bassetto,” music critic of the Daily News, and my father combined singing as a profession with Freethought printing as an industry. They went to concerts together and criticized one another’s work. Mrs. Besant would sing at times, but, alas! gifted as she was with the orator’s silver tongue, she had not the singer’s golden voice. Delightful days, full of hope and promise! If one man alone could defeat the House of Commons, could not a group so highly gifted as the Fabians put the world to rights? The future was their plaything.

When, a few years later, Bradlaugh, gravely ill, resigned the presidency of the National Secular Society, George Standring, who was very friendly with Shaw, would have liked him to take a more active part in militant Freethought, and Shaw lectured the society on Progress in Freethought. Shaw was under the impression that Standring wanted him to take Foote’s place as president. It was even proposed that Shaw should meet Bradlaugh in debate on Socialism. Of this Shaw wrote later in a letter to The Freethinker: “I was afraid of his enormous personal force… he was a hero, a giant who dwarfed everything around him.”

Although Shaw declared in his speech at the Bradlaugh centenary meeting that he was himself “ten times as much an Atheist as he was before I ever met him” he rejected the term Rationalist, or Materialist.

Although Shaw declared in his speech at the Bradlaugh centenary meeting that he was himself “ten times as much an Atheist as he was before I ever met him [Bradlaugh],” he rejected the term Rationalist, or Materialist. “My objection,” he wrote to me in 1935, “to the Roman Catholic Church is its inveterate and thrice-damned Rationalism… I think men are no good until they get religion [as defined by G.B.S.]. Now the R.P.A. will not have religion at any price: and they are quite right according to their definitions… I am much more of a Quaker than a Rationalist.”

Shaw, the successful dramatist, drifted far from the Freethinking circles of sixty years ago; but he always kept a friendly corner of his memory for Arthur and Hypatia, and on the one or two occasions I had to call at Whitehall Gardens, or earlier Adelphi Terrace, he seemingly enjoyed recalling the past; for he also had in him a streak of the “simple and sincere.”

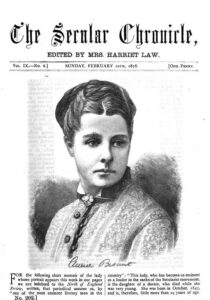

The object of Secularism is the promotion of human happiness in this world… [The Secularist] believes the surest way of […]

Purity of life, sincerity of action, obedience to law, love of our fellow creatures, all those qualities which ennoble life […]

A cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant […]

For I am not everlasting, but a human being, a part of the whole as an hour is a part […]