You can always appeal to common decency, which the vast majority of people believe in without the need to tie it up with any transcendental belief.

George Orwell, letter to Humphrey House, 11 April 1940

George Orwell is one of the most celebrated English authors and essayists of all time, and was a practical humanist who rejected ideas of immortality in favour of the here and now. Since his death in 1950, his works have been subject to much discussion, as have his ideas about religion.

Orwell expressed atheist beliefs in his writings and endorsed a humanist philosophy throughout his life, while also noting a concern that diminishing religious conviction might leave a moral vacuum in its wake. His solution, though, was a humanist one. What was needed, he wrote in 1940, was to ‘reinstate the belief in human brotherhood without the need for a “next world” to give it meaning.‘ Orwell could not believe in divine creation, an omnipotent god, or life after death. He decried the Catholic Church as being ‘against freedom of thought and speech, against human equality, and against any form of society tending to promote earthly happiness’, yet he always retained a certain sentimentality for Christianity, even directing that he be buried according to the rites of the Church of England. Despite these apparent contradictions, he was always a rationalist who cared deeply for humanity; an activist who focused on this world, rather than a proffered next. His unique worldview was dubbed ‘idiosyncratic humanism’ by Nicolas Walter.

One must choose between God and Man, and all ‘radicals’ and ‘progressives’, from the mildest Liberal to the most extreme Anarchist, have in effect chosen Man.

George Orwell, ‘Reflections on Gandhi’ in Shooting an Elephant and other Essays (1950)

George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair in Motihari, Bengal, India in June 1903. A member of what he referred to as the ‘lower-upper-middle class’, he won a scholarship to St Cyprian’s preparatory school in Sussex, and then to Eton. Despite his academic success, Orwell came to resent the British intelligentsia and decided not to continue with his classical education at university. Instead, he spent time as an imperial policeman in colonial Burma before moving back to Britain, taking up a job in a Hampstead bookshop, and beginning his own literary career. By this time, according to Peter Faulkner, he was ‘a thoroughgoing agnostic’, influenced partly by his own early struggles with Christian teachings, and partly by his reading of works by a host of rationalists and reformers.

Orwell was a prolific writer, producing nine books and a slew of essays, critiques, and reviews over his relatively short time as an author. In particular, he was known for his articulate defence of democratic socialism, his anti-totalitarian stance, and the championing of what he referred to as ‘the ordinary person’. Orwell spent much time in active participation with the working classes of Britain – taking whatever jobs were offered to him and recounting the experience in his first full-length novel Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). However, despite his journalistic writings, Orwell is most famous for two allegorical works of fiction: the world-renowned novella Animal Farm (1945) and the dystopian caution Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), both of which were written within the last five years of his life. Both works dealt with the looming threat of totalitarianism, addressing the ways in which it could arise from seemingly innocuous origins and be perpetuated through control, manipulation, and indoctrination.

In all his writings, Orwell emphasised the absolute importance of freedom of belief and expression, and highlighted the dangers of groupthink. In his preface to Animal Farm, he wrote:

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech — the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don’t convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice.

While Orwell seldom mentioned religion in his more prominent works, his atheism is widely acknowledged, and humanistic ideals pepper his essays. Recounting the religious backdrop against which he was raised, Orwell claimed that he began to question his belief – or perhaps to explore his lack of it – at the age of 14. He wrote of his belief that organised religion was no longer able to convince ‘the ordinary person’ of the everlasting soul and was increasingly being exposed for what it was: ‘in essence, a lie’. Though Orwell maintained that this was a good thing – and that such beliefs were patently untenable – he worried about what may come to replace them, particularly in light of the horrors of war and totalitarianism. In a 1940 article for Time and Tide, though, he gestured towards what this could be, and noted that it was already discernable in men’s willingness to fight and die ‘because of abstractions called “honour”, “duty”, “patriotism” and so forth’. ‘All that this really means,’ Orwell suggested, ‘is that they are aware of some organism greater than themselves’:

People sacrifice themselves for the sake of fragmentary communities — nation, race, creed, class — and only become aware that they are not individuals in the very moment when they are facing bullets. A very slight increase of consciousness, and their sense of loyalty could be transferred to humanity itself, which is not an abstraction.

George Orwell, ‘Notes on the Way’ in Time and Tide, 6 April 1940

In other writings too, Orwell expressed beliefs that display his humanism clearly. In his posthumously published Reflections on Gandhi, for instance, Orwell challenged a growing tendency to ignore the ‘other-worldly’ aspects of Gandhi’s philosophy, and argued that:

Gandhi’s teachings cannot be squared with the belief that Man is the measure of all things, and that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have.

Adopting the words of Protagoras and concisely summarising the beliefs of many humanists today, Orwell offered a rare reflection upon the personal philosophy that guided his works and his life. He went on:

But it is not necessary here to argue whether the other-worldly or the humanistic ideal is ‘higher’. The point is that they are incompatible. One must choose between God and Man, and all ‘radicals’ and ‘progressives’, from the mildest Liberal to the most extreme Anarchist, have in effect chosen Man.

George Orwell, ‘Reflections on Gandhi’ in Shooting an Elephant and other Essays (1950)

This emphasis on human beings – and of choosing the visible world rather than chasing an invisible hereafter – was the heart of Orwell’s humanism. Not only was it the case for him, he suggested, but also the case for the majority of people, who chose life by living it. A ‘normal human being does not want the Kingdom of Heaven’, Orwell wrote: ‘he wants life on earth to continue’. As such:

…it is the Christian attitude which is self-interested and hedonistic, since the aim is always to get away from the painful struggle of earthly life and find eternal peace in some kind of Heaven or Nirvana. The humanist attitude is that the struggle must continue and that death is the price of life… Often there is a seeming truce between the humanist and the religious believer, but in fact their attitudes cannot be reconciled: one must choose between this world and the next. And the enormous majority of human beings, if they understood the issue, would choose this world. They do make that choice when they continue working, breeding and dying instead of crippling their faculties in the hope of obtaining a new lease of existence elsewhere.

George Orwell, ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’ in Shooting an Elephant and other Essays (1950)

George Orwell died of tuberculosis in 1950, less than a year after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four. He was 46.

The humanist attitude is that the struggle must continue and that death is the price of life… Often there is a seeming truce between the humanist and the religious believer, but in fact their attitudes cannot be reconciled: one must choose between this world and the next. And the enormous majority of human beings, if they understood the issue, would choose this world.

George Orwell, ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’ in Shooting an Elephant and other Essays (1950)

George Orwell’s influence on literature, political thought, and popular culture can hardly be overstated. His candid style and lucid prose are instantly recognisable and his warnings against totalitarianism have, for the most part, been heeded; in fact, superfluous control exerted by a state over its population’s personal lives is now frequently indicted as ‘Orwellian’.

In 1984, Antony Flew wrote that ‘anyone seeking a paradigm of Humanist values can scarcely do better than to look to Orwell’. He understood human nature for human nature: recognising the influence and allure of political power while nevertheless seeing the goodness in humankind, and the possibilities of humanity. He placed great importance on self-flourishing, human equality, and freedom of thought, and on creating the conditions necessary for these. His 1949 statement of belief ‘that Man is the measure of all things, and that our job is to make life worth living on this earth, which is the only earth we have’ is a sentiment which remains at the heart of humanism today.

George Orwell | Humanists International

Blair, Eric Arthur [pseud. George Orwell] | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Nicolas Walter, ‘George Orwell and Humanism’ in The New Humanist, December 1998

George Orwell: a Life by Bernard Crick (1980)

By Alex Mortimer

Main image: George Orwell, c. 1940 by Cassowary Colorizations, licensed CC BY 2.0

The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge. Neither love without knowledge, nor knowledge without love […]

The tremendous influence of Moore and his book on us came from the fact that they suddenly removed from our […]

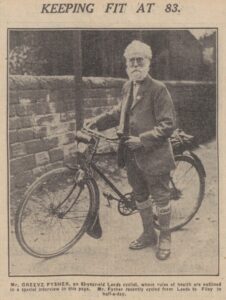

Mr. Fysher was in many respects a remarkable man. His interests were wide, and whatever he took up he carried […]

Oh what a tissue of inconsistencies are the dogmas in which we have been reared! Emma Martin, God’s Gifts and […]