Godlessness is negative. It merely denies the existence of god. Atheism is positive. It asserts the condition that results from the denial of god.

Gora, An Atheist With Gandhi (1951)

Gora was an Indian humanist of international prominence, who advocated a ‘positive atheism’ focused on equality, action, openness, and freedom. Driven by these values, he devoted his life to campaigning for human rights and social welfare, challenging superstition and the systems of oppression rooted in it. With his wife and fellow activist Saraswathi Gora, he founded the Atheist Centre, which continues to operate as a base for promoting humanism, providing education, and encouraging social cohesion. Major figures in the UK humanist movement, including Harry Stopes-Roe and Jim Herrick, found much to admire in Gora’s commitment to social action and international cooperation.

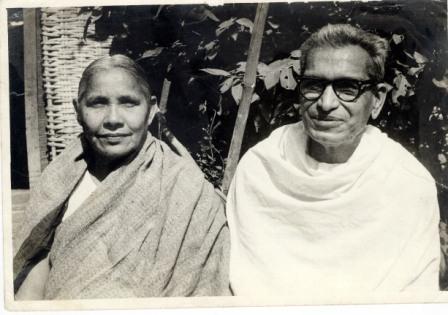

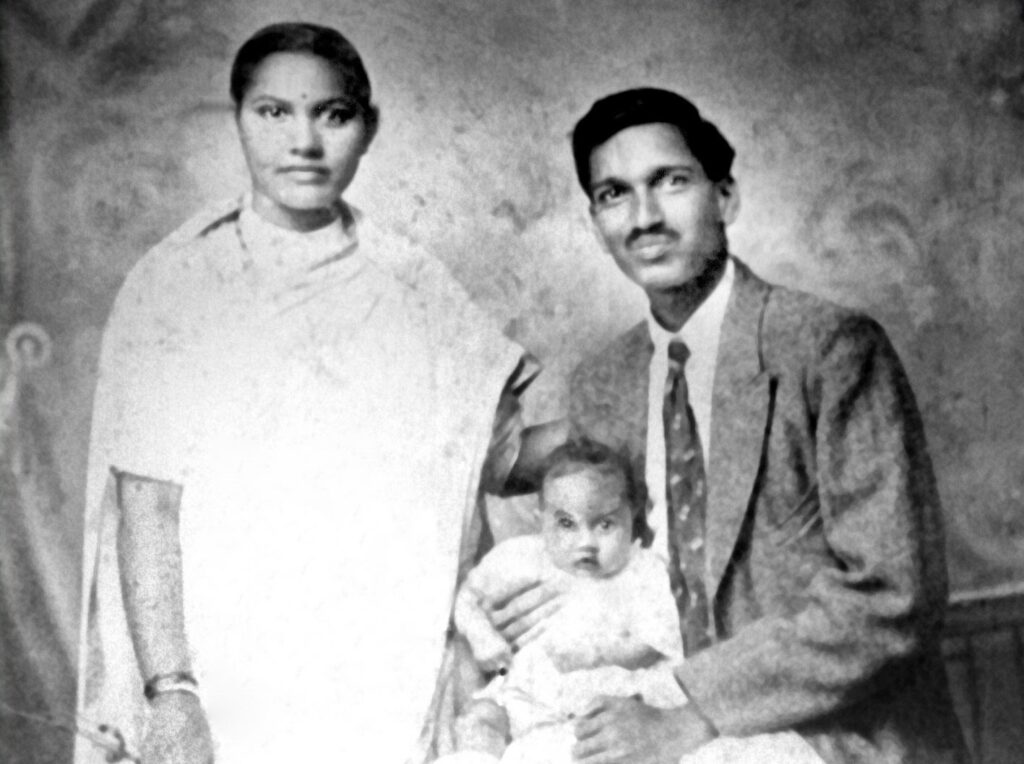

Goparaju Ramachandra Rao, known as Gora, was born into a high caste Hindu family in Chatrapur, east India. In We Become Atheists, he described being ‘conventionally orthodox and superstitious’ in childhood, but pursued science, earning a master’s degree in botany. As was customary within their culture and caste, Gora married Saraswathi in 1922 when she was just ten years old, tradition requiring girls to be married before reaching puberty. The reality of this, and other harmful practices sanctified by religion and tradition, ultimately strengthened both in asserting rationality, compassion, and positive atheism as tools of radical reform. Saraswathi became an active part of promoting atheism as a positive philosophy, and the two were partners in decades of work for social reform.

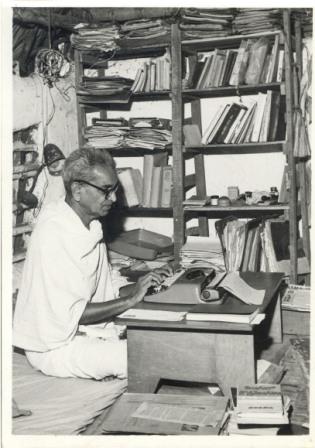

Gora taught botany in a series of colleges for fifteen years, simultaneously working to challenge injustice and champion reform. He argued for permitting the remarriage of widows, for increased access to education, and against the concept of the ‘untouchable’ caste. Both he and Saraswathi stood against superstition, notably when she, while pregnant, went outside and undertook work during a solar eclipse, said by Hindu tradition to cause birth defects. The birth of a healthy child was a powerful argument against the blind following of custom. Welcoming the label of ‘atheist’, Gora was dismissed from more than one teaching position on account of his activism and denial of religion. In 1940, he and Saraswathi founded the Atheist Centre in the village of Mudunuru, the first of its kind in the world.

The Atheist Centre promoted atheism as a way of life, emphasising the value of science and reason, and working for education and social reform. This included programmes of adult education, tours of rural villages promoting rationalism and popular science, the continuing fight against untouchability, the promotion of widow and inter-caste marriages, and promoting social cohesion through ‘cosmopolitan dinners’ and other efforts to break down caste divides. They were also actively involved in Gandhi’s Quit India Movement, demanding an end to British rule in India, and advocating satyagraha (non-violent resistance). Both Gora and Saraswathi were arrested in the course of their efforts. Gora’s conversations with Gandhi on the subject of the positive philosophy of atheism were later published as An Atheist with Gandhi.

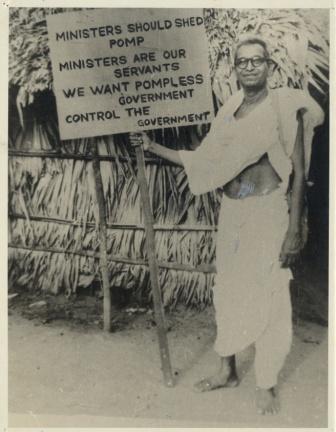

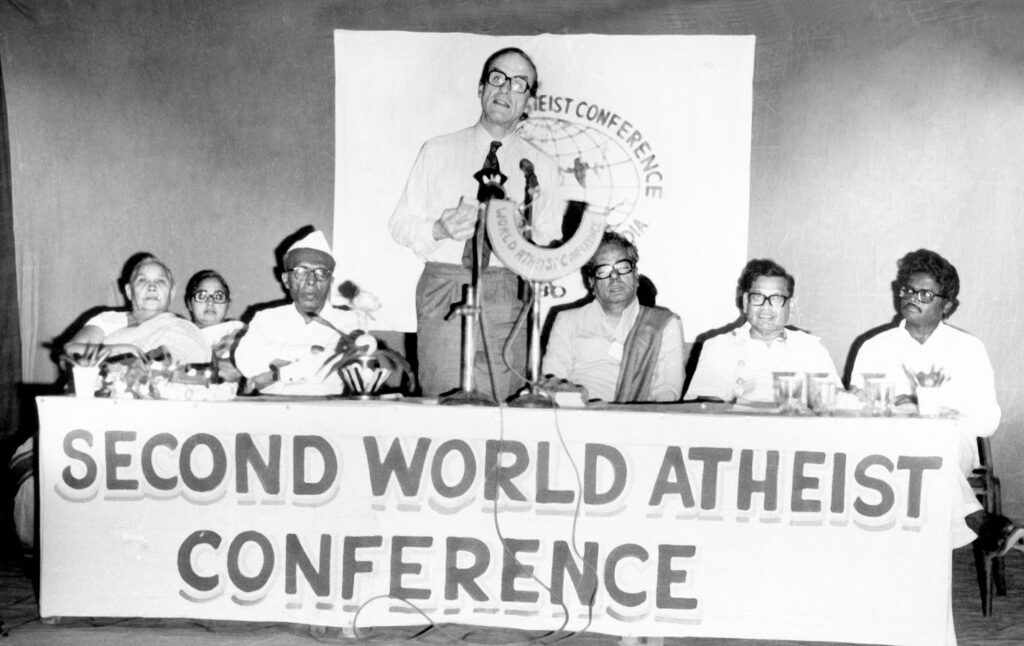

The Atheist Centre moved to Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh in southeast India in 1947, continuing the exhaustive programme of reformist efforts. Gora himself continued to promote atheism and democracy among the villages of India, including calling on ministers and public officials to shed ‘pomp’ and associate with the people. In 1952, Gora ran for Parliament as a partyless candidate, advocating radical reforms for greater social and political equality. In 1970, Gora attended the World Humanist Congress in Boston, organised by the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International) with the theme ‘To Seek a Humane World’. Two years later, on 22-26 December 1972, Gora staged the First World Atheist Conference in Vijayawada.

Gora died suddenly on 26 July 1975, while addressing a meeting at Vijayawada. Following his death, Saraswathi continued to lead the Atheist Centre, until her own death in 2006. In 2020, the Centre celebrated 80 years of ‘striving for [the] eradication of superstitions, inculcating [a] rational, scientific and secular outlook’, and ‘spreading positive atheism and humanism as a way of life’.

The atheist way of life is full of initiative. It continually progresses towards increasing happiness every time through scientific understanding and technological control of the forces of the world. Its objective is equality; its method is openness; its means is political action; its driving force is the moral freedom of the individual.

Gora, Positive Atheism (1972)

Gora’s example, and that of the Atheist Centre, was a significant influence on members of the international and UK humanist movements, inspired by the unstinting focus on positive action and social change. Prominent figures within the UK movement visited the Atheist Centre and attended its conferences, describing their experiences in writings and lectures at home. Among these were humanist educationist Harry Stopes-Roe, who lectured at South Place in 1990 on ‘Indian Atheism and British Humanism’, and Jim Herrick, who highlighted the significance of international humanism, including in his Presidential Address at the Sixth World Atheist Conference, 2007:

Atheism can be necessary in three spheres: the international, the regional and the personal. It is obvious to all that the clear light of atheism is needed in the international scene – not just as a contrast to religion, but also because of its values. Atheism can lead to equality of treatment, to the practice of human rights, the consideration of individuals and groups of people in widely different situations, tolerance of differences, and freedom of speech for religion and to criticize religion, a broad global separation of religion and state.

This emphasis on world humanism, and its positive possibilities, continues in the work of Humanists International today, promoting the central values of reason, compassion, secularism, and cooperation, exemplified by Gora and his Atheist Centre.

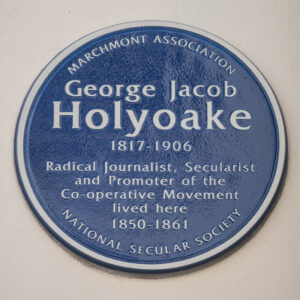

On Woburn Walk is a plaque to George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), a writer, lecturer, and promoter of the Cooperative movement, […]

Mr. Fysher was in many respects a remarkable man. His interests were wide, and whatever he took up he carried […]

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

The obituary reproduced below was written by George Broadhead, and originally appeared in a 1997 issue of The Gay Humanist […]