Faith without works is not Christianity, and unbelief without any effort to help shoulder the consequences for mankind is not Humanism.

Harold Blackham, Objections to Humanism (1963)

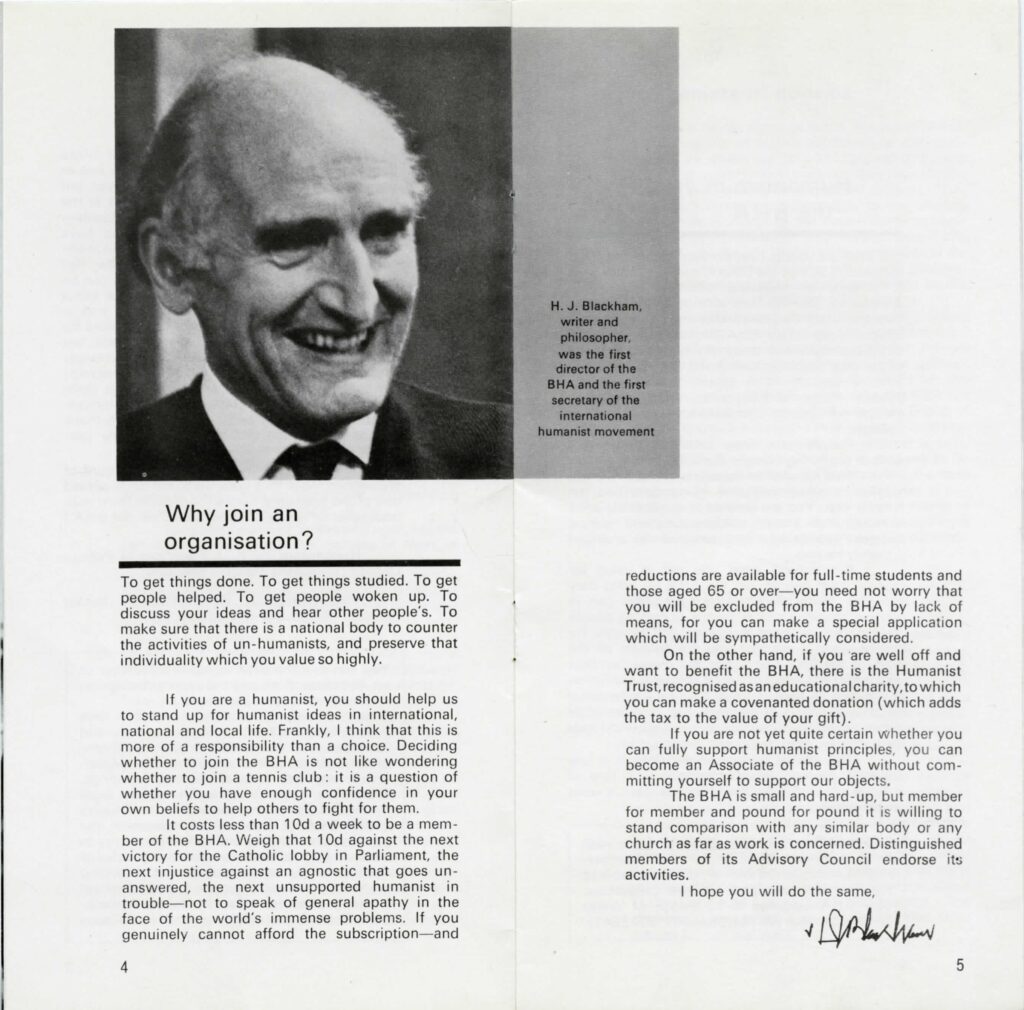

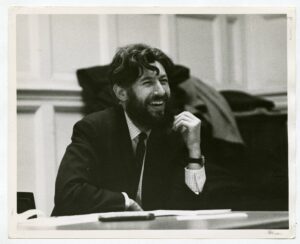

Harold Blackham was the architect of the modern humanist movement, and a decades-long champion of humanist values on national and international levels. As well as being the first Executive Director of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), he co-founded the International Humanist and Ethical Union, and the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy, overseeing many pioneering schemes for the active application of humanist principles to social reform. Beginning his career in Stanton Coit’s Ethical Church, Blackham nevertheless stripped the humanist movement of its quasi-religious elements, reshaping it to reflect and promote human possibility on its own terms.

Harold John Blackham was born in Birmingham in 1903, the son of Harriet Mary and Walter Roland Blackham, a bookseller. Having left school early, Blackham worked for a number of years as a farm labourer, before returning to education, graduating with a BA in 1924. The following year, he obtained a secondary teaching diploma. He taught for two years at a grammar school in Doncaster, as well as for the Workers Educational Association.

In 1932, Blackham began working for Stanton Coit at his Ethical Church in Bayswater, London, succeeding him as leader when he retired the following year. He later became chair of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), a post he held for over a decade. At the Ethical Church he met Olga Florence Rock, a teacher, who he married in 1934 and with whom he adopted a son. He spent these years lecturing widely, and developing his ideas on the history, tradition, and practice of humanism.

On the death of Stanton Coit in 1944, Blackham became Secretary of the Ethical Union, officially beginning a conscious shaping of the modern humanist movement. That year, he launched The Plain View, a humanist journal which would run for over 20 years. The subsequent decades also saw the publication of Six Existentialist Thinkers (1952), The Human Tradition (1953), Objections to Humanism (1963), and Religion in a Modern Society (1966), all of which gave expression to the long history of humanist ways of being. Living as a Humanist, published in 1950, contained contributions from Blackham, artist Ursula Edgcumbe, educationist (and daughter of Stanton Coit) Virginia Flemming, and M.L. Burnet, an active figure in the Humanist Housing Association. These essays sought to define humanism as a lived philosophy, asking ‘what does it really mean to be a humanist in any sense that is more than merely the refusal to be a Christian?’ As Andrew Copson has written, Blackham:

…did not want solely to give form and substance to the idea of humanism; he wanted also to create a movement that would promote this approach to life and engage in practical work to improve the condition of humanity.

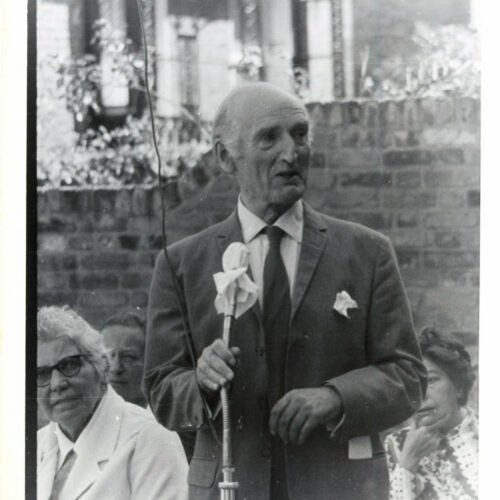

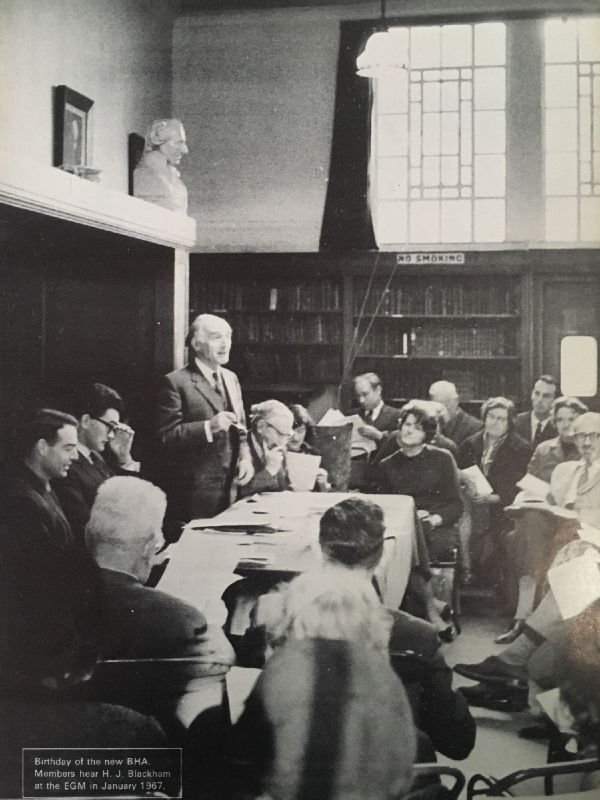

This was evident in Blackham’s active efforts as Director of the BHA, and in the initiatives arising during the 1950s and 1960s under his leadership, placing the improvement of human welfare at their heart. Among these were the Humanist Housing Association, the Agnostics Adoption Society, and the Humanist Counselling Service, each of which embodied a practical humanism, addressing areas in which Church provision was typically dominant, and often disadvantaged the non-religious. Blackham was also a firm believer in the role of dialogue and cooperation, helping to create – and chairing for many years – the Social Morality Council, which brought together Christians, Jews, and humanists in the discussion of moral issues. As befitted his own teaching background, and the long tradition of humanist efforts for non-theological education, Blackham was also actively involved in the promotion of moral education. He established the Campaign for Moral Education, and co-founded the Journal of Moral Education in 1971.

Central also to Blackham’s belief in the potential of the humanist movement was cooperation on a national and international level. As a longtime director of the Rationalist Press Association, he worked hard to enable a union of the RPA, National Secular Society, and Ethical Union under the umbrella of the Humanist Association. He also, in 1952, orchestrated the creation of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International), with Dutch humanist Jaap van Praag, and maintained active correspondence with humanist leaders across the world.

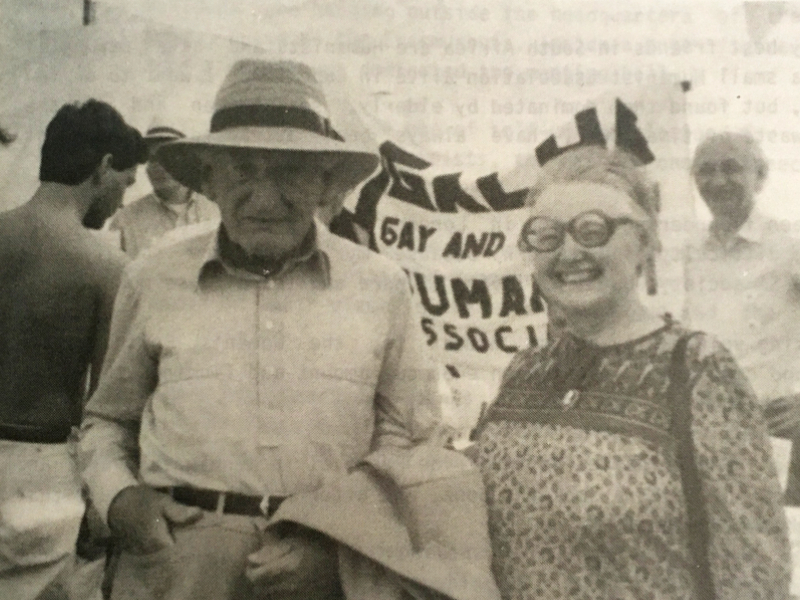

Following the death of his first wife, Olga, in 1977, Blackham married Ursula Ulalia Edgcumbe, his co-author on Living as a Humanist and longtime member of the humanist movement. The two moved to a peaceful home overlooking the Wye Valley in Herefordshire, where Blackham continued to read, write, volunteer, and officiate humanist funerals, as well as growing fruit and vegetables. He moved into a nursing home in 2008, and died the following year, at the age of 105.

The humanist prescription for the good life, then, is an open orientation of the self, responsive to the world, affirming it and taking responsibility for it, and by use and enjoyment of the actual and the present venturing into the ideal and the future… Such a prescription applies equally well to a great career on the grand scale and to ordinary living in the humblest way.

Harold Blackham in Living as a Humanist (1950)

Harold Blackham is deservedly remembered as the architect of the modern humanist movement, working to refine, express, and embody the values of humanism in his own life, and in the organisations he founded and ran. Many other leading humanists, notably Barbara Smoker, acknowledged Blackham as their ‘chief mentor’, not only in terms of defining the humanist philosophy, but in the example of his ‘life and his caring fellowship’, as Smoker recalled. For Blackham, humanism was the expression of compassion and the creation of meaning, perhaps typified by his response to the outbreak of the Second World War. Here, he assisted Jewish refugee children escaping Nazi persecution, drove fire engines throughout the Blitz, and made an impassioned statement for the continuing significance of the humanist movement in times of national crisis.

The form, shape, and focus of Humanists UK and the international humanist movement would not be as they are without the existence and example of Harold Blackham. He lived, as Jim Herrick has written, ‘the exemplary humanist life, that of thought and action welded together.’

…a slowly growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war… is not in consequence of any […]

I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as […]

Conscious morality cannot exist in any being except so far as it can look behind, before, and around; and can […]

When we stand up for freedom of conscience, for the rights of the individual, for the rational approach and against […]