Good writing excites me, and makes life worth living.

Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter was one of the 20th century’s most influential dramatists: a humanist and activist described by his biographer Michael Billington as ‘a permanent public nuisance, a questioner of accepted truths, both in life and art’. Pinter was a member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), and in 2002 was among more than 100 public figures who protested to the BBC over a ban on atheist contributors to BBC Radio 4’s Thought For The Day.

Born into a family of Ashkenazi Jews in 1930, Harold Pinter was a solitary child. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the young boy possessed a wonderful imagination and attentiveness. The young Pinter grew up in a traumatic climate; he experienced terrible loneliness as a result of being evacuated to Cornwall during the Second World War, and returned to London at the height of the Blitz, where death and destruction were everywhere. The shocking mundanity of such horrors left a big impression on Pinter, and the inquisitive child’s love of reading framed and sculpted his impressively acute sense of mortality and the preciousness of human life.

Pinter’s passion for literature continued to thrive during his time at Hackney Downs Grammar School, and under the tutelage of his English teacher, Joseph Brearley, Pinter discovered the power and joy of drama. He began acting in school plays, and devoured and dissected passages from playwrights such as John Webster. For the first time in his life, too, he fell in with a group of friends with whom he could share such passions. The warmth and intensity of these platonic relationships inspired much of his early writing, yet Pinter would not find fame as a writer for some time. He instead spent much of the 1950s working multiple little jobs to supplement his career as a jobbing actor.

When he wasn’t appearing in a range of repertory shows across the country, Pinter continued to quietly write, penning mainly poems and short pieces of prose. While his acting career struggled to really take off during this time, the experience would prove invaluable for honing his skills as a playwright. He was able to learn a great deal about stagecraft and artistic structure, and submitted his first public play, The Room, at the request of his old friend Henry Woolf, who put on the play with his university drama department in 1957. Rave reviews resulted in the play running at the National Student Drama Festival later that year and, by 1960, with the staging of the commercially successful The Caretaker on the West End, Pinter had announced himself as one of the country’s most prominent, exciting and thought-provoking playwrights.

His 1965 work The Homecoming further enhanced his reputation, and he began to turn his talents to the screen as well as the stage. Many of his works were adapted into films or television series, and he penned still more from scratch, such as The Servant (1963), or adapted other writers’ works, such as The Pumpkin Eater (1964). The following years also saw Pinter return to acting, starring on both stage and screen alongside actors such as Judi Dench, Pierce Brosnan and Emma Thompson. Right up until the 2000s, Pinter would continue to move seamlessly between roles, garnering enormous respect for his vision and humanity, as an actor, director and, foremost, as a writer.

Pinter was also very active politically throughout his life. The injustices and destitution he witnessed first-hand as a child gave him a passionate commitment to supporting and defending human rights, and giving a voice to the voiceless. He instinctively mistrusted authority, whether that be governments and political institutions or the divine authority of a religious deity. He was also a prominent anti-war activist and voiced his opposition to a string of military conflicts; he became a conscientious objector in the aftermath of the Second World War and was an outspoken critic of Western governments for their involvement in wars such as the Kosovo campaign and the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Pinter’s political interventions were very often brusque and divisive. Both the content of some of his views and the manner in which he aired them saw him receive criticism from many corners, with some even objecting to the decision to award him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2005. Yet Pinter was never abashed, and stuck proudly to his convictions until the day he died.

I’ve never been able to write a happy play, but I’ve been able to enjoy a happy life.

Harold Pinter to The New York Times, 2007

Harold Pinter was a man deeply motivated by a desire for a more peaceful world. He saw in humanity a fragility and preciousness which was both beautiful and terrifying; themes which underline much of his dramatic work, and which motivated him throughout his life. He was also a man of strong conviction, with – in the words of Michael Billington – a ‘lifelong belief in the right of the individual conscience to resist the demands of the State’. Many also described Pinter’s ‘almost sacred belief in friendship’, and these emphases on freedom of thought, personal conscience, and human relationships epitomise his humanism. Pinter’s devotion to examining the human condition, and to working for a more humane world, inspired many, and these guiding values continue to underpin the work of Humanists UK today.

Josephine Gowa was an active member of the Hampstead Ethical Institute (later Hampstead Humanist Society) for over three decades, many […]

I don’t think it’s the novelist’s job to give answers. He’s only concerned with exposing the human situation… and I […]

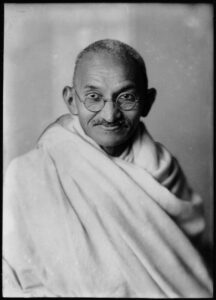

The international significance and reputation of Mohandas Gandhi is well-known, but his involvement with the burgeoning humanist movement during the […]

From the outset IAS aimed to have an open approach to prospective adopters irrespective of their race, religion and creed, […]