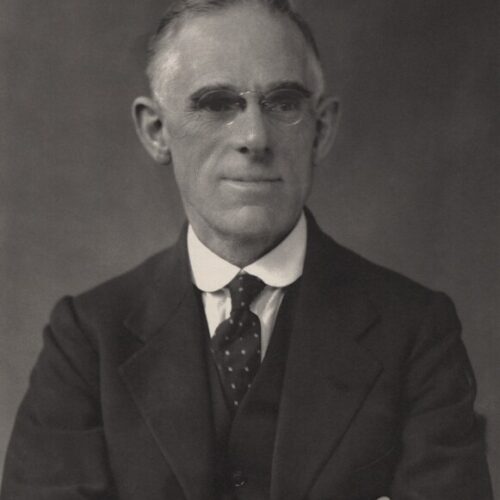

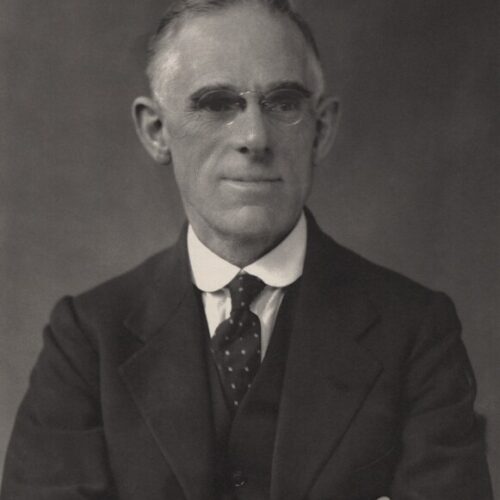

Harry Snell was a socialist politician and campaigner, a devoted advocate of the Ethical Movement and a key figure in the varied work of the Union of Ethical Societies (today’s Humanists UK).

From humble beginnings and largely self-educated, Snell rose to become chairman of the London County Council, and deputy leader of the House of Lords. Known as ‘a man of much grace and goodness’, Snell was a lifelong champion of social causes, whose active humanism was evident in all aspects of his life and work.

Henry (Harry) Snell was born on 1 April 1865 in the village of Sutton-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, and raised by his mother and stepfather. Though given a ‘sporadic and rudimentary’ education at the village school, from the age of eight he was working as a cattle minder and bird scarer, and by ten as a farm labourer. Following a period as a servant in Newark, Snell moved to Nottingham, finding work in a succession of public houses. Here, he began reading widely and attending evening classes at University College, Nottingham. Influenced by religious nonconformism in the village of his childhood, Snell also attended freethought lectures, and briefly a Unitarian church, but eventually found a home in the humanist movement.

From a clerical post at the Midland Institution for the Blind, Snell moved to London in 1890 to become assistant to the secretary of the Woolwich Charity Organisation Society. Already committed to socialism, he also became active in the Independent Labour Party, as well as in the Ethical Movement. From 1895 he was secretary to the first director of the London School of Economics, William Albert Samuel Lewins, and then a lecturer for the Fabian Society. Snell was appointed organiser and lecturer for the Union of Ethical Societies in 1899. He went on to become chairman of the Union and, between 1907-1931, secretary of the Secular Education League. Snell was a county councillor for East Woolwich between 1919-1925, and elected to parliament as an MP in 1922. He accepted a peerage in 1931 as Baron Snell, of Plumstead, Kent; a title that became extinct on his death. In 1934, Snell was elected chairman of London County Council, an office he held, according to Lord Latham, ‘with a dignity, ability, and urbanity which marked him as one of the greatest chairmen the council has ever had.’ From 1940, he was the deputy leader of the House of Lords.

In spite of his prominent role in the political sphere, Snell himself described religious and ethical questions as being those of greatest significance to him. In his 1936 autobiography, Men, Movements and Myself, he wrote

although political and Labour questions arrested my attention, and made constant demands on my time and energies, my deepest and most abiding interests were in religion and ethics, and to these great subjects that the best thought and work of my life has been given.

This found its truest expression in his active devotion to the work of the Union of Ethical Societies. For almost half a century, Snell lectured, organised, and advocated for the Union, noted for his ‘forceful, rugged, albeit humorous eloquence.’ Snell was the Union’s secretary from 1906-1919, and its chair 1922-1936. During WW1, he visited conscientious objectors in Wandsworth Prison, taking copies of Stanton Coit’s Ethical Message with him. His commitment to peace and international understanding was another feature of his political values, as well as evident in his role as vice-chairman of – and one of the earliest public figures to support – the British Council.

Snell died at the age of 79 on 21 April 1944. His funeral service, conducted by H. J. Blackham at Golders Green Crematorium, made use of passages from the Ethical Church’s Ethical Funeral Service, a volume for which Snell himself had written a preface. Clement Attlee also offered recollections. An additional service, commemorating his public works and attended by over 300 people, took place in Westminster Abbey.

Speaking in the House of Lords on 25 April, Viscount Cranborne said

if, as was the case, Lord Snell was a great man, it was not merely on account of his abilities. His greatness was a greatness of spirit, and he irradiated an essential goodness all too rare in the world. He had an innate simplicity of heart and an absolute moral integrity which never led him to compromise his convictions.

Moving as he did from bird scarer to baron, it was said that Snell was ‘the first man in England to rise from the level of the rural poor to a position in the titled governing class’. He was, as printed in a tribute sent to The Times, ‘a man of transparent honesty and unflinching courage’, and a thoroughgoing humanist in thought and deed. Recollections of Snell consistently referred to his kindness, integrity, and devotion to the causes of social and ethical reform. Speaking at his funeral, Attlee affirmed that

[a]lthough he is dead his influence remains. Harry Snell devoted his life to the service of humanity. No man I have known had less care of himself or more for others. He lived an ascetic life. He had an enthusiasm for his causes lighted up by personal charm and a sense of humour. Goodness shone out from him… He was a great citizen of the world and a very great gentleman. He has passed away full of years and honours, and with the respect and affection of all who knew him.

I am willing and eager to surrender as much of my personal sovereignty as is necessary, in order to secure […]

Max Gate is the former home of Thomas Hardy in Dorchester, Dorset. Hardy designed and lived in Max Gate from 1885 until […]

Lillie Boileau was a devoted figure within the Ethical movement, and an active part of the fight for women’s suffrage. […]

As well as being one of the most distinguished musicians of his time, he was, like Sir Hubert Parry before […]