I felt flattered by the remark of a hostile journalist that I was “a compendium of the cranks,” by which he apparently meant that I advocated not this or that humane reform, but all of them. That is just what I desire to do.

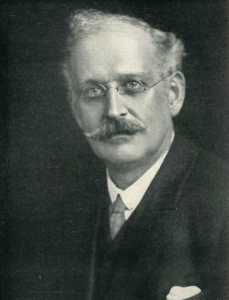

Henry S. Salt, The Creed of Kinship (1935)

Henry S. Salt was a classical scholar, animal rights campaigner, and founder of The Humanitarian League. Mahatma Gandhi credited Salt with showing him why ‘it was right to be vegetarian’, and Salt counted among his close friends George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter, and James Ramsay MacDonald. Defining himself as a rationalist, Salt proposed a humanist ‘creed of kinship’, predicated on the ultimate duty of humankind to protect the vulnerable and care for one another.

It would be impossible to sum up more gloriously, in a single line, the essence of piety, of human goodness, than in Shelley’s words: “To live as if to love and live were one.”

Henry S. Salt, The Creed of Kinship (1935)

Henry Shakespear Stephens Salt was born on 20 September 1851 in Nynee Tal, India, where his father Thomas Henry Salt was serving in the British Army. The following year, he returned to England with his mother, Ellen Matilda. Salt was educated at Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge, where he received the Browne Medal for Latin and Greek poetry, and from which he graduated with a first class degree in the Classical Tripos.

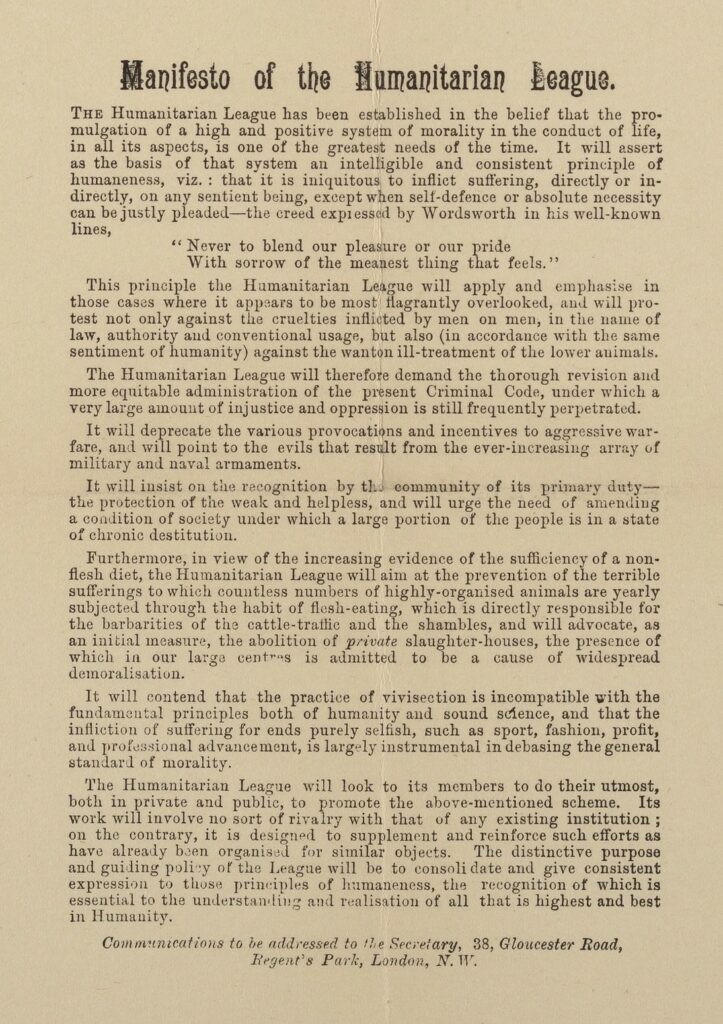

For nearly ten years from 1875, Salt was an assistant master at Eton College. In 1879, he married Catherine Leigh Joynes (known as Kate), with whom he remained until her death in 1919. Salt left Eton in 1884, decrying his fellow masters as:

but cannibals in cap and gown – almost literally cannibals, as devouring the flesh and blood of animals … and indirectly cannibals, as living by the sweat and toil of the classes that do the hard work of the world.

Salt settled into a life of simple vegetarianism and prolific publishing. From this point on, he published a huge number of books and pamphlets on a variety of themes, including works of translation, reminiscence, literary criticism, biography, nature writing, and calls for reform. Among these were: A Plea for Vegetarianism (1886); Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Monograph (1888); Life of Henry David Thoreau (1890); The Ethics of Corporal Punishment (1907); The Nursery of Toryism: Reminiscences of Eton under Hornby (1911); Our Vanishing Wildflowers (1928); and a verse translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1928).

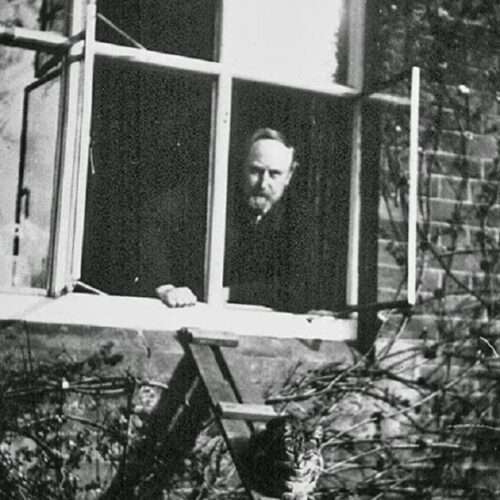

In 1891, Salt founded The Humanitarian League, uniting his myriad interests in social reform and working towards ‘humanising… the conditions of modern life.’ For nearly three decades he worked for the League, also editing its two journals Humanity, later The Humanitarian (1895-1919), and The Humane Review (1900-1910). In June 1898, Salt was best man for George Bernard Shaw (a fellow League committee member) at his wedding to Charlotte Payne-Townsend.

In 1919, Salt’s first wife Kate died, and he stepped down from his position as Honorary Secretary of The Humanitarian League, which disbanded the same year. In 1921, he published his autobiography Seventy Years Among Savages.

Central to Salt’s work and life was an adherence to rationalism, and a deep respect for all sentient beings – human and animal – from which his humanitarianism and vegetarianism sprang. Of religion he wrote:

Religion has never befriended the cause of humaneness. Its monstrous doctrine of eternal punishment and the torture of the damned underlies much of the barbarity with which man has treated man; and the deep division imagined by the Church between the human being, with his immortal soul, and the soulless “beasts”, has been responsible for an incalculable sum of cruelty.

Instead, Salt proposed The Creed of Kinship, outlined in a book of that title published in 1934. At the heart of this ‘creed’ was Salt’s belief that ‘the basis of any real morality must be the sense of Kinship between all living things,’ as well as the centrality of free thought to human progress. In a review of the book, The Daily Herald described Salt as ‘[o]ne of the kindliest men living’. He happily accepted the epithets of those who considered him an eccentric:

He felt flattered, he tells us, when a hostile journalist described him as “a compendium of the cranks,” by which, says Mr. Salt, “he apparently meant that I advocated not this or that humane reform, but all of them. That is just what I desire to do.”

The Observer, 15 September 1935

Salt died in Brighton on 19 April 1939 at the age of 87, and was survived by his second wife Catherine (née Mandeville), who he had married in 1927.

As a reformer he was happily gifted with a sense of humour and the power of seeing his opponent’s point of view; but these qualities did not detract from his sincerity.

The Times, 20 April 1939

Henry S. Salt’s deep concern for humanity, belief in kinship, emphasis on free and rational thought, and creed of kindness place him squarely amongst the influential humanists of history. In his advocacy for humane reforms, and tireless work towards them, his was an activist humanism, which viewed organised religion as in many ways a barrier to equality and social change.

Charles Albert Watts was a lifelong promoter of rationalism, and the founder in 1885 of Watts’s Literary Guide, still published […]

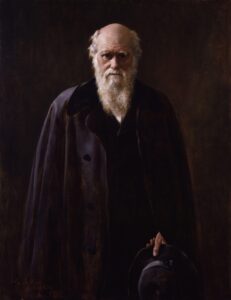

I cannot pretend to throw the least light on such abstruse problems. The mystery of the beginning of all things […]

The Rationalist Press Association (later known as simply the Rationalist Association) had its origins in the London print works of […]

By Steve Ratcliff Steve has been researching humanists from LGBT history, focusing on digitised materials from the archives of LGBT […]