No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; no one can be perfectly happy till all are happy.

Herbert Spencer, Social Statics (1850)

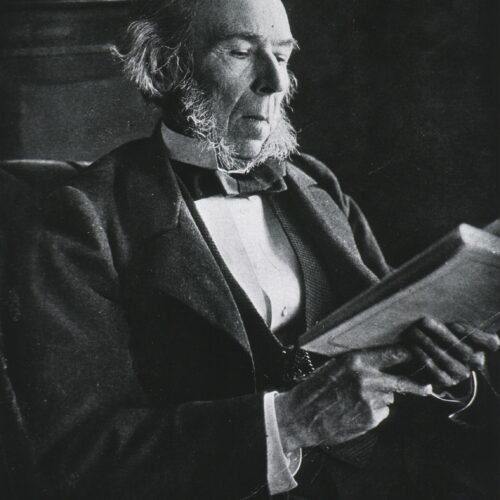

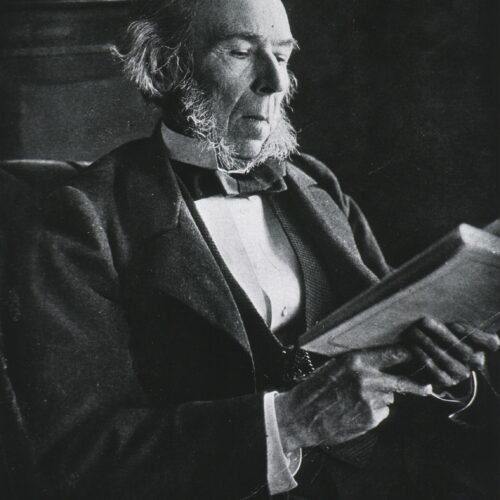

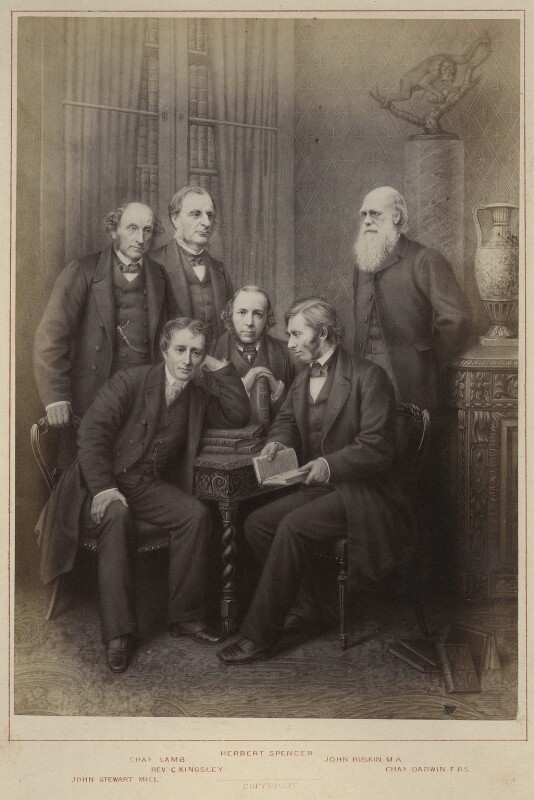

Herbert Spencer was a philosopher, sociologist, and writer who, as an early evolutionary thinker, coined the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’ to describe Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Widely known for his agnosticism, Spencer was close to many other progressive thinkers and religious sceptics among his contemporaries, including T.H. Huxley, John Tyndall, John Stuart Mill, G.H. Lewes, and George Eliot. Though his reputation oscillated during his lifetime and after his death, Spencer was a significant influence on Victorian thought, including pioneers of humanist philosophy. George Jacob Holyoake, for one, described him as ‘the greatest master of innovatory thought England has produced’.

People are beginning to see that the first requisite to success in life is to be a good animal.

Herbert Spencer, Education (1861)

Herbert Spencer was born in Derby, England on 27 April 1820. He was one of nine children born to William George Spencer, a headmaster and tutor, and Harriet (née Holmes), but was their only child to survive beyond infancy. His father was a religious nonconformist, and Honorary Secretary of the Derby Philosophical Society, where reform, rationalism, science, and innovation were central topics of discussion. All of this influenced the young Herbert Spencer, who early on embraced the agnostic philosophy which characterised his thinking. After tutoring by his father and uncle, he undertook an apprenticeship as a civil engineer, but eventually devoted himself entirely to a literary career.

Spencer is most recognised today for using the ideas of biology and evolutionary theory to inform his views on society. His most influential publication was A System of Synthetic Philosophy (1862-96), in which he sought to bring together his ideas of biology, sociology, ethics, and politics. Spencer was an early exponent of evolutionary theory, explored in his Principles of Psychology (1855). He later embraced Charles Darwin‘s theory of natural selection, and coined the phrase the ‘survival of the fittest’ to describe it in Principles of Biology (1864). He did, however, give significant weight to Lamarckian ideas of inherited traits and acquired characteristics, a recurring theme in his writings which would later cause his reputation to suffer. Regardless, he was a staunch – and significant – defender of evolutionary theory and its implications, writing in 1852:

Those who cavalierly reject the theory of Lamarck and his followers, as not adequately supported by facts, seem quite to forget that their own theory is supported by no facts at all. Like the majority of men who are born to a given belief, they demand the most rigorous proof of any adverse doctrine, but assume that their own doctrine needs none.

Like his close friend, T.H. Huxley (who became known as ‘Darwin’s bulldog’ for his own vociferous defence of evolutionary science), Spencer rejected the possibility of proving the existence (or non-existence) of a god. In his autobiography, he wrote:

I hold that we are as utterly incompetent to understand the ultimate nature of things, or origin of them, as the deaf man is to understand sounds or the blind man light. My position is simply that I know nothing about it, and never can know anything about it, and must be content in my ignorance. I deny nothing and I affirm nothing… I am content to leave the question unsettled as the insoluble mystery.

Spencer emphasised instead the ‘natural laws’ which governed the world, and believed that concepts of morality could be derived from these, with no need for revealed religion. He believed ‘there must be a basis for morals in the nature of things — in the relations between the individual and the surrounding world, and in the social relations of men to one another.’ Like others who argued for a distinction between concepts of religion and morality, he recognised in 1862’s First Principles that ‘volumes might be written upon the impiety of the pious.’ In an 1891 essay, Spencer expressed his belief that ‘absolute morality is the regulation of conduct in such a way that pain shall not be inflicted’.

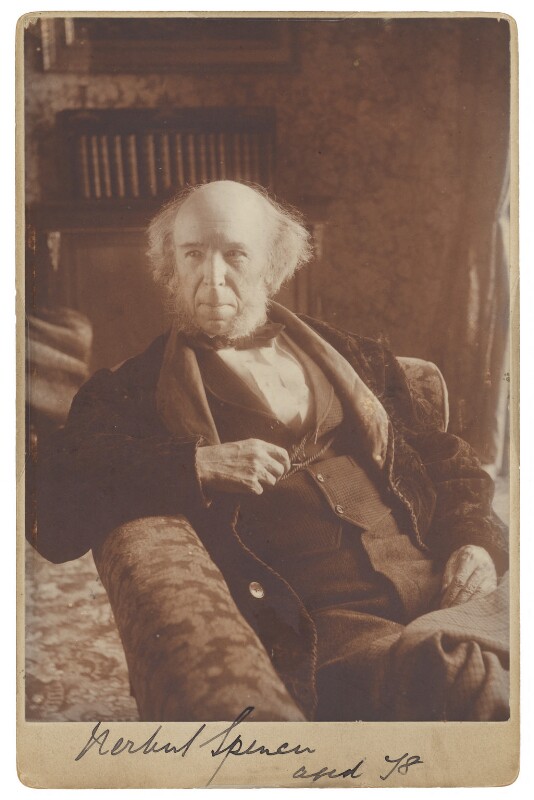

Throughout much of his life, Spencer suffered ill health, including the effects of a nervous breakdown during the 1850s from which he never fully recovered. In his later years, he was increasingly viewed (including by friends) as a hypochondriac, suffering from a variety of unrecognisable maladies. He died in 1903 at the age of 83, and was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium. His ashes were interred in Highgate Cemetery.

[Herbert Spencer‘s] noble life, so disinterested, so pure, so devoted to the service of man, needed no consolation higher than his own conscience. His glory was that he laid down new landmarks of guidance in all the dominions of human knowledge.

George Jacob Holyoake, The Literary Guide, January 1904

Spencer, widely recognised as an agnostic, was enormously popular within ethical and humanist circles, and his works widely promoted by the Rationalist Press Association. He exercised significant influence in the Victorian era, both in the UK and internationally, even being nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1903. Though his reputation has fluctuated, his emphasis on self-reliance, individual human rights, and a secular morality drew many admirers, as did his lifelong pursuit of a practical philosophy, cut loose from religious notions. A fascinating man and innovative thinker, as The Humanist put it in 1957, ‘to the connoisseur of human character and eccentricity he ought to be irresistibly attractive.’

An Autobiography by Herbert Spencer (1904)

‘First Use of the Phrase ‘survival of the fittest” | The British Library

‘The Complicated Legacy of Herbert Spencer’ | Smithsonian Magazine

Herbert Spencer papers | Senate House Library, University of London

To say that “God moves in mysterious ways” is to put up a smokescreen of mystery behind which fantasy may […]

Humanism is a philosophy of life based on a concern for humanity rather than a belief in god. Humanists believe […]

Mary Sheepshanks was a humanist who saw her feminist, pacifist, and cosmopolitan beliefs as being natural expressions of her humanist […]

Humanists International was formed in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU): a federation of the American Ethical […]