It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies.

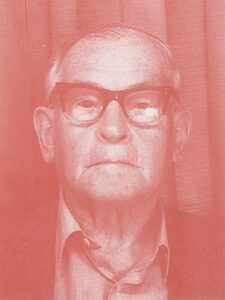

Hermann Bondi, Humanism – the only valid foundation of ethics (1992)

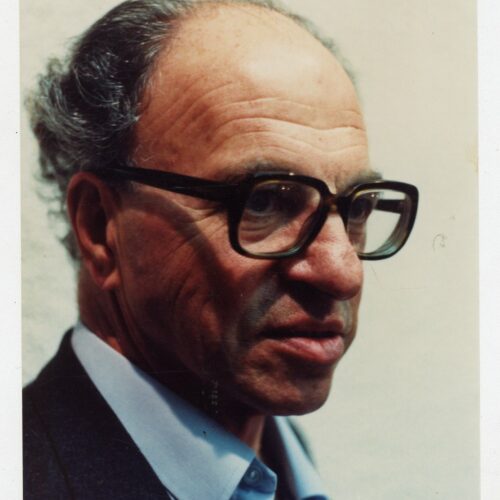

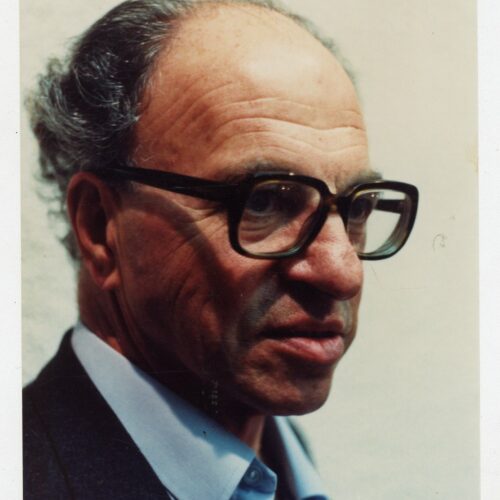

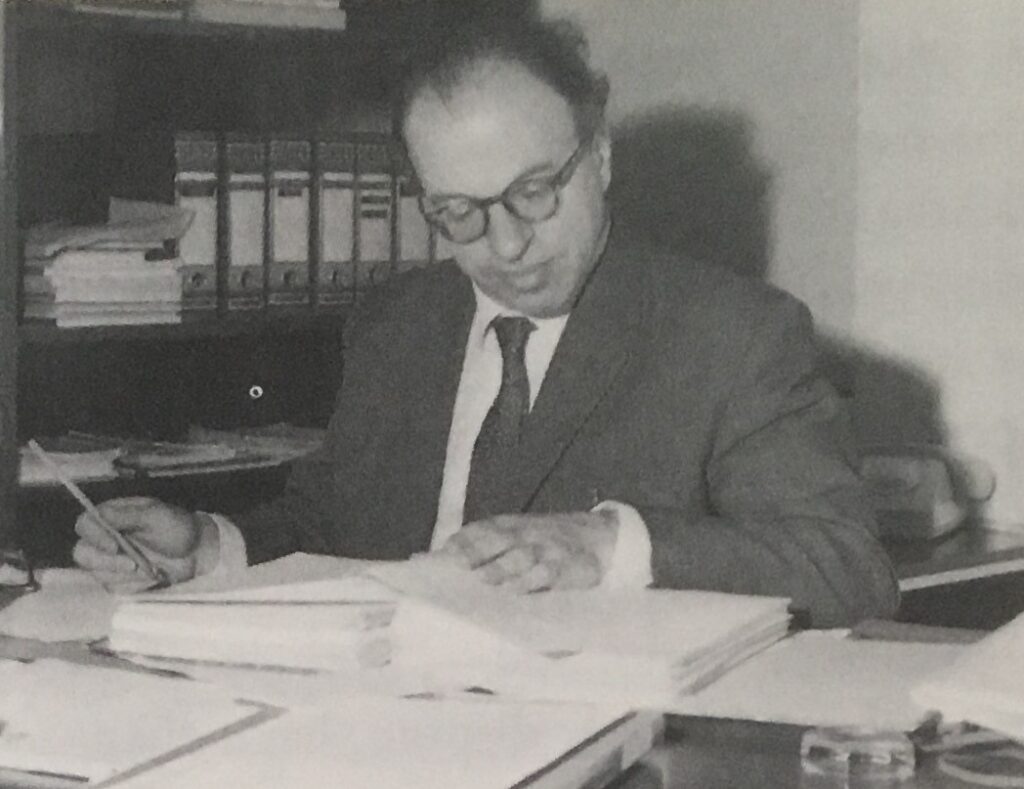

Hermann Bondi remains the longest serving President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), holding the title for nearly two decades. A remarkable mathematician and cosmologist, Bondi was also an eloquent proponent of humanism, who did much to shape and propel the movement. Inspired by, and a supporter of, Indian humanists in their work to tackle inequality and superstition, Bondi believed in working actively with others to improve the world for everyone. This, and a passionate curiosity, made him a great scientist and a consummate humanist.

Hermann Bondi was born in Vienna in 1919, into a non-observant Jewish family, and Bondi himself was a lifelong atheist. Writing of Bondi after his death, Jane Wynne Willson noted that while his father, a doctor, ‘regarded orthodox Judaism as a kind of social cement’, his German mother disliked it all. Both attitudes, Wynne Willson suggested, combined in their son, who grew to embrace opportunities for cooperation with the religious, but retained an irritation with aspects of religion he found harmful or nonsensical.

Mathematically gifted (and passionate) from childhood, Bondi applied to and entered the University of Cambridge in 1937, going straight into the second year. He excelled, but in 1940, as an Austrian citizen, he was interned as an ‘alien’. Transported to Canada, Bondi and others established a camp ‘university’, at which Bondi lectured. This formative experience, during which Bondi held forth without the help of books or notes, shaped his subsequent lecturing and broadcasting career, and secured his capacity for doing so without aids.

In the years following his release in 1941, Bondi made his early marks in the fields of mathematics and astronomy. By the middle of the decade, he was back at Cambridge as a fellow and lecturer, where he met and married his wife, Christine. The couple went on to have five children. They were actively involved in local humanist groups from the 1950s onwards, and both retained their engagement with the movement – at home and internationally – for the rest of their lives. Both incisive mathematicians, Hermann and Christine collaborated in applications of maths to theoretical physics.

In 1954, Bondi went to King’s College, London, where he established an international research centre in general relativity. He also became increasingly interested in the communication of science to the wider public, giving talks for television and radio, and publishing popular and widely translated books. Among them were The Universe at Large (1961), Relativity and Common Sense (1964), and Assumption and Myth in Physical Theory (1968). In 1967, he became Director-General of the European Space Research Organization, playing a decisive role in transforming its formerly shaky financial and political standing. He subsequently became chief scientific adviser to the Ministry of Defence, then to the Ministry of Energy, before being appointed chairman and chief executive of the Natural Environment Research Council.

Bondi’s commitment to humanism was no less significant than to science. He served as President of both the British Humanist Association, and the Rationalist Press Association, for nearly two decades from the beginning of the 1980s to the end of the 1990s. As such, he remains the longest serving President of Humanists UK. Bondi was also inspired by, and actively involved in, Indian rationalism and efforts to challenge superstition, the caste system, and poverty. On winning a prestigious international prize, he used his prize money to financially support the Vijayawada Atheist Centre, and the work of distinguished humanist and doctor Indumati Parikh’s among women in the slums of Mumbai. Bondi was also a longtime, and devoted, worker for Save the Children.

Bondi spent his final years in Cambridge, where he had been employed from 1983. On retirement in 1990, he and Christine moved to Impington. In 1992, he delivered a Conway Memorial Lecture titled: Humanism – the only valid foundation of ethics. Ethics, he said:

… is about living with other people, ethics is about being members of a peaceful and reasonably harmonious (I trust not too harmonious, that would be dull) human society. So ethics can only come, can only be based on, a real belief in human beings. And that is what we call Humanism. I would not wish to deny that is a faith, but I say that the only logical basis for living with others is to value others.

Hermann Bondi died on 10 September 2005, having lived a life in which this characteristic humour, eloquent turn of phrase, and lived devotion to humankind, had truly made a difference to society, and to science.

Writing for the New Humanist after Bondi’s death, Jane Wynne Willson wrote:

The humanist movement has indeed been fortunate to have enjoyed the unswerving support and example of such an exceptional and delightful man over such a long period.

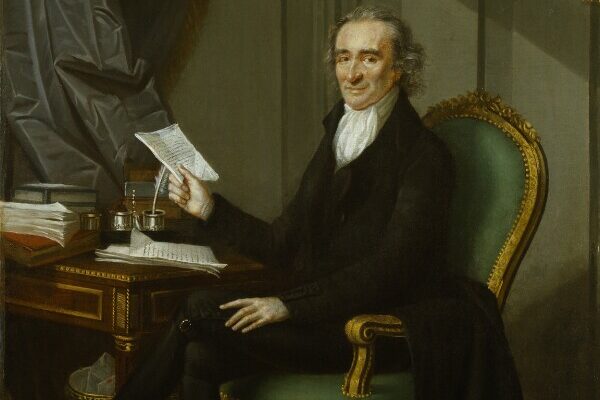

While Bondi’s legacy as a mathematician, scientist, and communicator was profound, so too was the firmly felt humanism which underpinned it. Bondi was motivated by a fascination with the workings and complexities of the world around him, which led him to maths and science. He was also imbued with a strong sense of the responsibility of human beings to one another, which led him to humanism. In his Conway Hall lecture, Bondi described the touchstones of the humanist approach: an embrace of difference, an applied empathy with others, and a flexibility of mind that comes with thinking for oneself. Beneath it all was the sense of community for which Bondi had always worked towards and within. For him, humanism meant ‘a willingness to change the world’:

… and I quote Thomas Paine: ‘We live to improve’, he said, ‘or we live in vain’. I am not quite clear from the context whether he means improving the world we live in or improving ourselves, indeed I am not at all sure he distinguished between the two. ‘We live to improve or we live in vain’, is a very wise saying. It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies.

To summarise why I have become a rationalist is a difficult task for one not educated in formal writing, but […]

There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… […]

For I am not everlasting, but a human being, a part of the whole as an hour is a part […]

I think that one of the most hopeful signs at the present day, and one for which this Movement can […]