The Victorian Age: the early 1800s to 1900

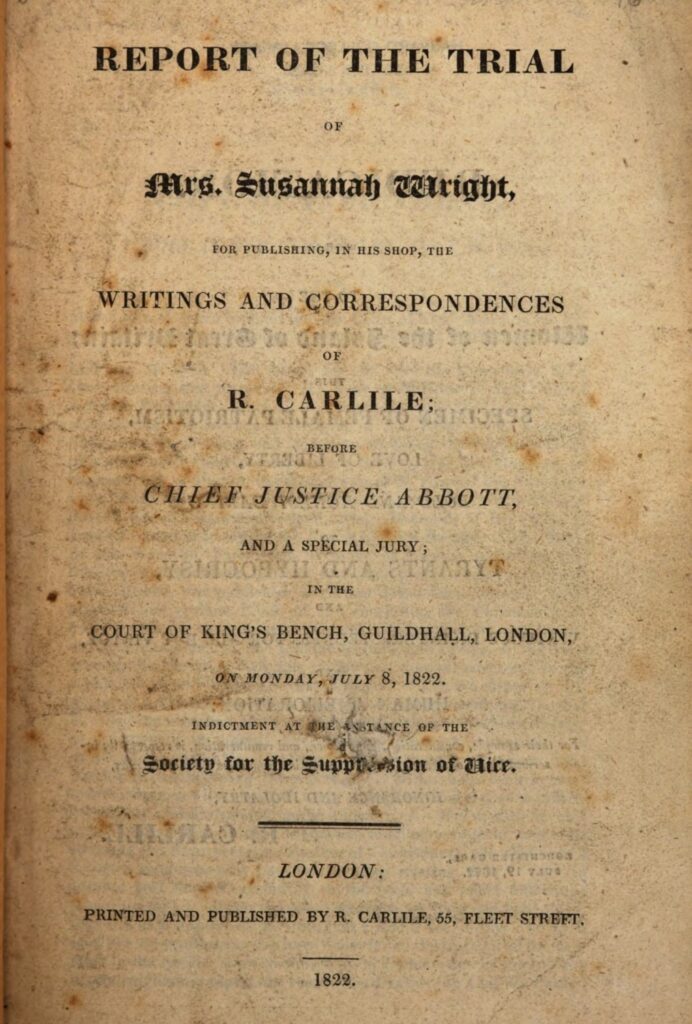

The early nineteenth century saw a Christian reaction against the growing humanism of the eighteenth century in the form of a Christian ‘Evangelical revival’ and political repression of freethinking, because of government fears about its potential for revolution.

But as the nineteenth century proceeded, scientific progress and advances in the study of history and further study of cultures outside of the western world stimulated a growth in humanist ideas. Ideas of human equality, equal citizenship, equality between men and women, and other liberal humanist ideas began to be expressed more clearly – and began to have a political effect.

The century also witnessed the growth of movements which were strongly secular in focus, emphasising social change along rational lines, and setting concepts of morality apart from religious ideas. These included the socialist Owenites, the positivists and their ‘religion of humanity’, the National Secular Society, and the ethical societies, forerunners of Humanists UK.

By the end of the Victorian age, there were many people in the UK whose beliefs were humanist rather than religious, and humanist community organisations of various kinds had formed.