Our age, with all its faults, is surely as capable of a sane ideal as any that went before; and the ideal of making Reason commensurate with action, and of making each day a conscious new beginning… is surely fittest for the age in which above all others every day brings forth a new thing.

John M. Robertson, ‘Concerning Regeneration’ in Essays in Ethics (1903)

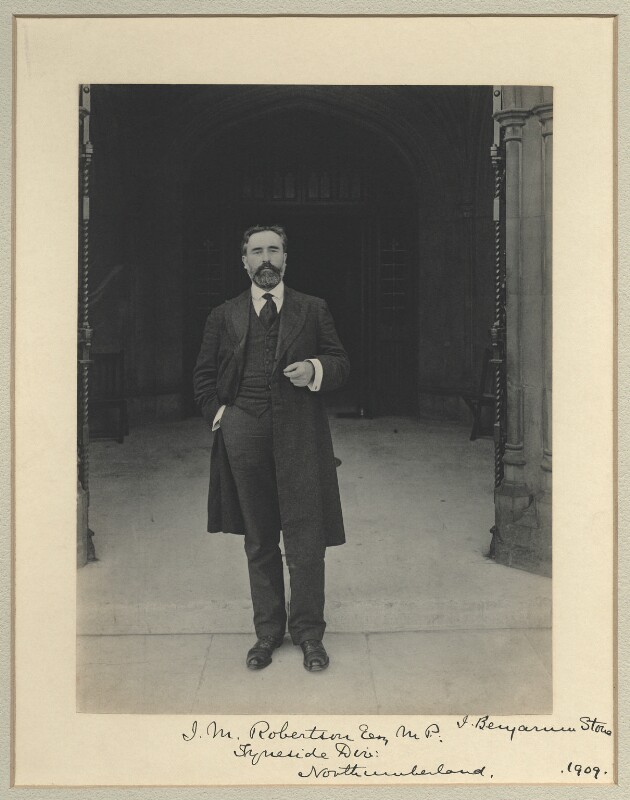

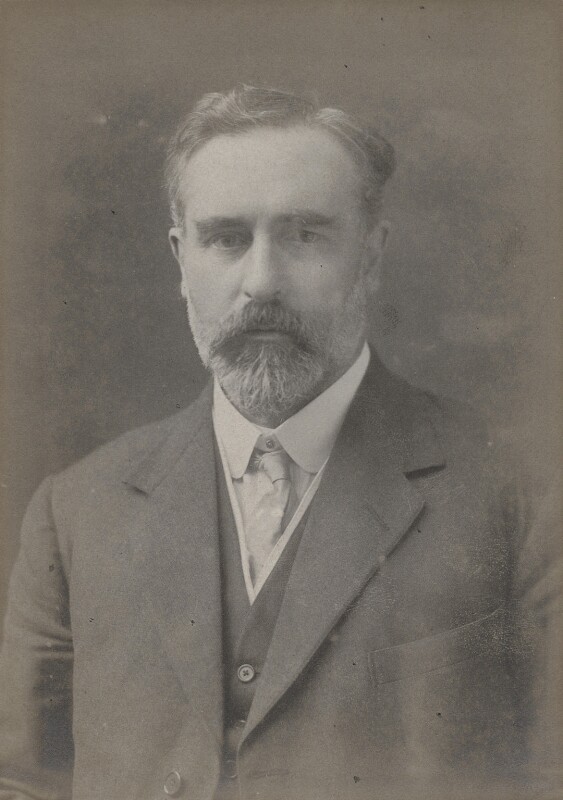

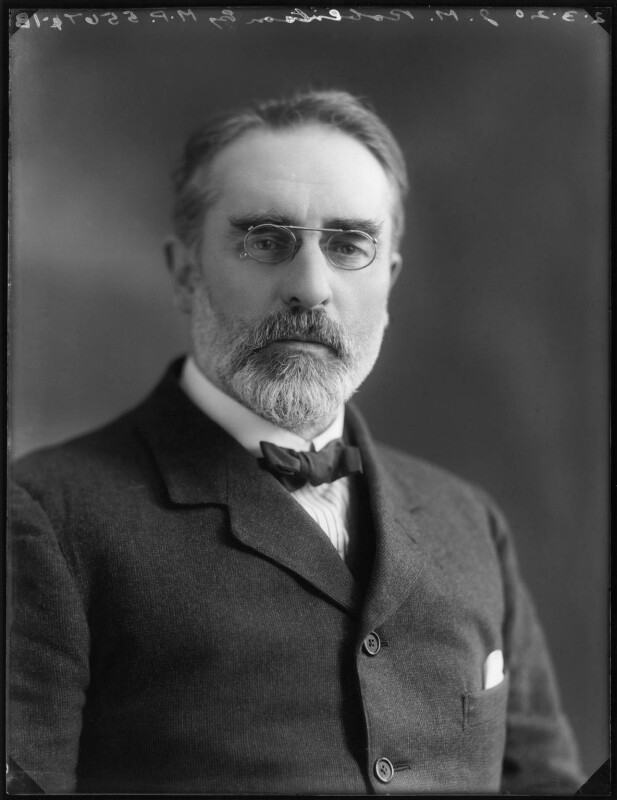

John Mackinnon Robertson was a Scottish journalist, writer, rationalist, and Liberal MP. A prolific author, he published works on a wide range of subjects including freethought, economics, history, and ethics. Robertson was active in the rationalist and secularist movements in both Scotland and England, and served as the Member of Parliament for Tyneside from 1906 to 1918.

The obituary and tribute reprinted below was first published in The Literary Guide, February 1933.

John Mackinnon Robertson

BORN NOVEMBER 14, 1856; DIED JANUARY 5, 1933

By the English-speaking people throughout the world, and indeed by many of those of other nationalities, the news of the sudden death of John M. Robertson on January 5 will ere now have been received with profound sorrow. In the special fields of historical research and literary criticism he was the premier representative of the Rationalist Movement, and he was generally recognized as a great scholar and an incomparable and fearless dialectician. Three months previous to his passing he had a slight stroke, from which it was hoped he was recovering; but the laborious life he had lived, continuous to the end, had left its impress, and with slight warning a second stroke shortly followed, accompanied by fatal results.

In the special fields of historical research and literary criticism he was the premier representative of the Rationalist Movement, and he was generally recognized as a great scholar and an incomparable and fearless dialectician.

There is little doubt that the tremendous labour involved in re-writing and bringing up to date his colossal undertaking, Courses of Study, was largely responsible for his collapse; but it was his irrepressible fascination for work he loved—evidenced by his lecturing at Conway Hall when he was really physically incapable and by later attending an important meeting of the Bradlaugh Centenary Committee—that hastened and effected the end.

And yet, if we try to think so, it was a glorious finish—in giving his best, even with failing breath, to movements he had always loved and worked for.

In accordance with the wishes expressed by Mr. Robertson when in health, his remains were cremated at Golders Green two days following his death, without ceremony of any kind.

In accordance with the wishes expressed by Mr. Robertson when in health, his remains were cremated at Golders Green two days following his death, without ceremony of any kind. Only a few friends heard of his passing, and consequently the attendance was meagre, not more than thirty members being present. They included Mr. Guy Robertson (the deceased’s son), representatives of the Rationalist Press Association, the National Secular Society, the Ethical Union, and the South Place Ethical Society, as well as Mr. John Burns and Mrs. Charles T. Gorham.

Mr. Robertson had just passed his seventy-sixth year, having been born in the Isle of Arran on November 14, 1856. As most of our readers know, he was self-educated, having left school at the age of thirteen.

Mr. Robertson had just passed his seventy-sixth year, having been born in the Isle of Arran on November 14, 1856. As most of our readers know, he was self-educated, having left school at the age of thirteen. As early as 1878 he occupied a prominent position on the staff of the Edinburgh Evening News. It was not long after that he removed to London, we believe at the invitation of Charles Bradlaugh, and thereafter he was a regular contributor to the National Reformer, ultimately becoming editor on the death of the great “Iconoclast.” He ran the journal for nearly three years, when it ceased publication through financial reasons. He soon after launched another journal, the Free Review, which four years later was transformed into the University Magazine and Free Review under the editorship of R. de Villiers (G. A. Singer).

In 1897–98 Mr. Robertson lectured throughout the United States, and in 1900 he accepted a commission from the Morning Leader to visit South Africa and report on the working of martial law in that country. It will be recalled that he was member for Tyneside for nearly thirteen years (1906 to 1918), was Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade from 1911 to 1915, and was made a Privy Councillor in 1915. From that time onward he devoted most of his activities to helping “the best of causes,” the joy of his youth and the mainstay of his whole life.

It will be recalled that he was member for Tyneside for nearly thirteen years (1906 to 1918), was Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade from 1911 to 1915, and was made a Privy Councillor in 1915. From that time onward he devoted most of his activities to helping “the best of causes,” the joy of his youth and the mainstay of his whole life.

The literary output of Mr. Robertson was enormous. On one of the advertisement pages of our present issue will be found a list of his Freethought works still in print. Nearly all his Shakespearean treatises were issued from other centres than Johnson’s Court, and a few of them may be expected to retain interest for admirers of the immortal poet. The book, however, by which Mr. Robertson will always be remembered by Rationalists is his masterly History of Freethought. Only eighteen months ago he re-drafted it for final publication in possibly four volumes, devoting nearly half a year to the arduous task. The MS. is now in one of the safes of the R.P.A., and it will probably remain there until the whole of the stock of the History of Freethought in the Nineteenth Century is exhausted.

There may be some truth in the allegation that his blunt and outspoken speech occasionally irritated friends, but there was no malice in what he said, and behind all his utterances there was a kindness of heart which, unfortunately, is somewhat rare among publicists. He was reputedly most careful and reliable as regards facts, and his extreme conscientiousness was frequently testified to by both friends and adversaries.

Although not endowed with the eloquence of Ingersoll or Bradlaugh, Mr. Robertson possessed remarkable oratorical powers, which enthralled audiences of a political as well as of a heterodox type. There may be some truth in the allegation that his blunt and outspoken speech occasionally irritated friends, but there was no malice in what he said, and behind all his utterances there was a kindness of heart which, unfortunately, is somewhat rare among publicists. He was reputedly most careful and reliable as regards facts, and his extreme conscientiousness was frequently testified to by both friends and adversaries.

“J. M. R”: A PERSONAL APPRECIATION

By J. P. GILMOUR, Chairman of the Rationalist Press Association

Of capital interest to us is the fact that he was primus inter pares in a group of five clever, eager, and enthusiastic Freethinkers, who as lecturers and workers for the Edinburgh Secular Society had attracted lively attention to it and given a notable impetus to Freethought propaganda in what was then, and still is, a stronghold of orthodoxy in Scotland.

IT is over fifty years since I first met John Mackinnon Robertson, or “J. M. R.” as he came to be familiarly and affectionately styled by his intimates and the many admirers of his career in and noble work for Rationalism. He was at that time leader-writer for the Edinburgh Evening News, with William Archer as a colleague on the staff. Of capital interest to us is the fact that he was primus inter pares in a group of five clever, eager, and enthusiastic Freethinkers, who as lecturers and workers for the Edinburgh Secular Society had attracted lively attention to it and given a notable impetus to Freethought propaganda in what was then, and still is, a stronghold of orthodoxy in Scotland. The members of this redoubtable group were (in addition to Robertson) Thomas Carlaw Martin, a Post Office administrator, afterwards editor of the Scottish Leader, who was given a knighthood for his editorial services in support of the legal case for the union of the United Presbyterian and Free Churches; W. E. Snell, of the Queen’s Remembrancer’s Office, a suave and scholarly exponent of Freethought doctrine; Joseph Mazzini Wheeler, a highly-strung, supersensitive being and a writer of uncommon ability and force; and John Lees, a business man, as chivalrous a soul as ever lived. In sympathy but not in open alliance with this gallant group were William Archer and Patrick Geddes, both afterwards Honorary Associates of the R.P. A. It was one of the conventions of the members of this unconventional brotherhood to wear hyacinthine locks, to have whiskers and a beard, and, for the platform, to sport a brown or black velvet jacket. These “insignia” were very becoming for “J. M. R.,” who had then, as to the end of his life, a fine manly presence; and later, when as a lecturer he “invaded” England, he was described as “the handsome Scotsman.”

It was one of the conventions of the members of this unconventional brotherhood to wear hyacinthine locks, to have whiskers and a beard, and, for the platform, to sport a brown or black velvet jacket. These “insignia” were very becoming for “J. M. R.,”… When as a lecturer he “invaded” England, he was described as “the handsome Scotsman.”

It was as one of the “star” lecturers for the Glasgow Secular Society, of which I was then Secretary, that my acquaintanceship with “J. M. R.” began. It soon ripened into the precious friendship that, despite his removal in 1884 to London to join the staff of Bradlaugh’s National Reformer, where I did not follow him until 1916, remained intimate and unbroken until the close of his life. For I lunched with him at the National Liberal Club in October, when he seemed to have nearly got over the slight stroke of paresis which he had in September. Indeed, so far had recovery from it proceeded that, by his doctor’s permission, “J. M. R.” kept the engagement to lecture for the South Place Ethical Society on October 16; and, although it was evident on that occasion that all was not well with him, his delivery was characteristically vigorous. This lecture, the subject of which, “Contaminated Ideals,” was a forcible defence of R. P. A. policy as against the ideas and proposals of the Scientific Humanists, was published in full in the January issue of the Literary Guide. In our talk after the lecture we agreed that this had probably been his last appearance on the lecture platform; but I had no presentiment that our parting then was also a final one. In the earlier period of his lecturing career “J. M. R.” wrote out his lectures in full; in the middle period he spoke from notes; and latterly there was a reversion to manuscript, chiefly with a view to publication; and a number of the lectures given before the South Place Ethical Society were issued by the Rationalist Press Association, under the title of Spoken Essays. Even when reading from his manuscript, which from first to last was in a fair, firm, legible, and running penmanship, Robertson’s delivery was easy, natural, and effective. His language and feeling could rise to heights of stately, chastened eloquence, but it was never flashily or cheaply rhetorical. As a writer, an art in which he had pre-eminent facility, his diction and style were always finely fitted for their purpose. He had a commandingly copious and rich vocabulary, of which, oddly enough, some people complained as if it were affectation; but at no time was it ever a mere pedantic parade of grandiloquence. On the contrary, the text was chosen with nice discrimination and sense of proportion to express his ideas and enforce his arguments.

The close reasoning of his spoken and written word demanded the sedulous and sustained attention of the listener to or reader of it, to whom he was apt some times to credit a higher intelligence and honesty than the circumstances justified. Those who had once looked upon “J. M.R.” as an academic thinker and an armchair politician and publicist were surprised to find in him, especially when he took to active political life, entered the House of Commons, and held office as Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade, a capable man of affairs and an efficient administrator. For example, he was generally acknowledged to be the leading authority on the affirmative side of Free Trade. It was not that he had any strong predilection for such a career, since what may be called the life of reason, the advancement of Rationalism and all it stands for, the love of letters and of culture in the highest sense of that much-abused term, were his ruling passions.

Even when reading from his manuscript, which from first to last was in a fair, firm, legible, and running penmanship, Robertson’s delivery was easy, natural, and effective. His language and feeling could rise to heights of stately, chastened eloquence, but it was never flashily or cheaply rhetorical.

He had a prodigiously capacious and retentive memory, especially for the printed word, and immense power of assimilation and collocation of all that he read. I often wondered how he had ever found time for the acquisition of the six or seven languages of which he had not merely a colloquial but also a critical knowledge, and for the vast amount of reading in extenso or for reference, represented by his library about 12,000 books. In a general way the foundation of his mastery of languages and encyclopaedic familiarity with literature had been laid in the formative years between his leaving school at thirteen and the beginning of his journalistic life in Edinburgh; but he never ceased to be an omnivorous reader, and yet not promiscuously, for his keen critical intelligence and judgment were applied to and profited by all that he read. There was nothing that “J.M.R.” touched in philosophy, belles lettres, history, biography, criticism, or in his monumental contributions to the special literature of Rationalism, that he did not illuminate and enrich by his profound knowledge and wisdom.

Those who knew Robertson only through his published works or by casual contacts with him on public occasions were apt to misjudge him as being austere and prone to asperity in controversy. Nothing could be further from the fact. He was one of the most catholic-minded and magnanimous of men, always willing and indeed eager to listen to anyone not in agreement with him. He often wasted precious time in giving audience to, or in disputation with, dunces and busybodies; but he belonged both by temperament and habit to that older generation of thinkers and friends of liberty who believed in and practised free speech, and so were not afraid or ashamed to say outright what they thought, conceiving that always the cause of truth demands courage and boldness of testimony on its behalf. We live in a transition age when compromise has been degraded into weak complaisance, and when, too often, the answer that should confute or expose error is a mumbled evasion of the issue.

Those who knew Robertson only through his published works or by casual contacts with him on public occasions were apt to misjudge him as being austere and prone to asperity in controversy. Nothing could be further from the fact. He was one of the most catholic-minded and magnanimous of men, always willing and indeed eager to listen to anyone not in agreement with him.

When I come to try to bear witness to all that “J. M.R.’s” friendship meant for me and all who were blessed with it, words fail me. Who can sum up all that his gracious example and influence yielded to us in vision, guidance, enrichment, and ennoblement of thought and life? In all his relationships, public and private, Robertson displayed the cardinal virtues of rectitude, candour, honesty, and courage. In the intimacy of family life he was a fond husband and a loving and devoted parent. By the friends who had the honour and happiness of years of intercourse with him his memory will be kept green by the image and impress of his cordial, companionable, and inspiring character, and of his forthcoming, sincere, and sympathetic spirit.

In all his relationships, public and private, Robertson displayed the cardinal virtues of rectitude, candour, honesty, and courage. In the intimacy of family life he was a fond husband and a loving and devoted parent.

Their most cherished and enduring remembrance of “J. M. R.” will not be so much that of the great scholar, intrepid assailant of all forms of error and superstition, and beneficent liberator of human thought, as of the warm-hearted sociable man, of so hospitable a disposition and service that he never grudged to spare time from his ten or twelve hours’ working day to entertain or advise an old friend. By his death Rationalism and civilization have lost a dominant personal force, and for all who knew him intimately their world has henceforth a void that can never be filled. And so, dear “J.M.R.,” Ave atque Vale.

Not by the Creed but by the Deed. Motto of the Society for Ethical Culture of New York, founded in […]

The Cambridge Ethical Society was established in 1888, inspired by the London Ethical Society (formed two years earlier). It aimed […]

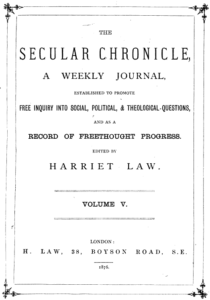

Harriet Law was a secularist and speaker, who also promoted women’s rights and socialist ideals. During the 1870s, Law’s house […]

I lost religion in a breath; Heaven fled from me on the wings of Reason… Doris Lessing, Under My Skin: […]