Belfast-born Jack McDowell was an activist, educator, politician, and atheist, whose humanism was evident in a lifetime of work for human rights, social welfare, and solutions to sectarian divisions. As Patrick Maume concludes in the biography reproduced here:

McDowell reflected a distinctive northern radical tradition and a motley body of civil society groups and activists who during the Northern Ireland troubles sought to open contacts between the warring factions, consider new approaches to politics, and offer non-sectarian solutions.

The biography reprinted below was first published in June 2014 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Maume, Patrick

McDowell, John William (‘Jack’) (1923?–2006), community activist and politician, was born in the Shankill Road area of Belfast. His father was a first world war veteran and member of the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP); although some of his relatives were active in the Orange order, McDowell followed his father’s political path. (Although McDowell was described as a protestant this was merely an ethnic description; he was an atheist.)

Although McDowell was described as a protestant this was merely an ethnic description; he was an atheist.

McDowell trained as a teacher, and in later life acquired degrees from QUB (in economics) and the University of Ulster (in phonetics). He joined the Royal Navy during the second world war after being challenged to join up when he addressed a public meeting in the Cornmarket in central Belfast demanding the immediate opening of a second front on the European continent to relieve German military pressure on the USSR. This decision went against the wishes of his father, who did not want his son to experience the horrors he himself had endured. McDowell was present at the Normandy landings of June 1944; although he rarely spoke of his experiences, the pain and suffering he witnessed influenced his later pacifism and advocacy of animal rights.

On returning from the war, McDowell pursued a teaching career, first at a primary school in Antrim town, then at Jordanstown School for the Deaf, where he worked for many years, eventually retiring as vice-principal. He was also a long-serving member of the NILP, serving for some time as its vice-chairman. As an NILP electoral candidate he generally put in a solid performance, but never won a seat. In the 1953 Stormont general election he won 30 per cent of the vote in the Ards constituency in a straight contest with the sitting Unionist MP, William May. His candidacy may have reflected a shortage of potential candidates in Ards, for his subsequent candidacies were all in the north Belfast area where he lived and worked. McDowell contested the Duncairn seat in a Stormont by-election on 4 December 1956 (polling 31.7 per cent) and at the Stormont general elections of 1962 (as part of a wider swing to the NILP in reaction against an economic downturn, he won 40.9 per cent) and 1965 (when he fell back to 35.4 per cent). At the 1969 Stormont general election McDowell switched to the newly created Newtownabbey constituency in the hope that its extensive housing developments and large population of industrial workers – combined with the fact that, as a new constituency many of whose inhabitants had recently moved from elsewhere, it might be less likely to have established voting patterns – would make it fertile territory for Labour; in the event McDowell polled only 25.7 per cent against the prominent liberal Unionist Robin Bailie. McDowell was also an unsuccessful NILP candidate for North Belfast in the Westminster elections of 1959 (35.2 per cent) and 1964 (34.9 per cent); these performances represented a slight increase in the Labour vote at the expense of unionism, and McDowell predicted that it would increase further in the future. (He attributed his 1964 defeat to the combined influence of rain and the new television show Doctor Who in keeping working-class voters at home. In later life he often recalled a voter who told him in 1959 that she had no interest in politics and therefore voted unionist as exemplifying what was wrong with the Northern Ireland situation.) Instead, the NILP was squeezed by the political strategy of Terence O’Neill (qv) of combining advocacy of economic modernisation and better communal relations, and with the outbreak of the Northern Ireland troubles lost most of its remaining support either to the new, cross-community Alliance party or to new groups on both sides of the deepening sectarian divide.

McDowell was present at the Normandy landings of June 1944; although he rarely spoke of his experiences, the pain and suffering he witnessed influenced his later pacifism and advocacy of animal rights.

As a member of the NILP, McDowell had accepted the party’s policy that partition should be accepted as the will of the majority of the population of Northern Ireland. After the party’s disintegration in the early 1970s, McDowell advocated Irish reunification, but stated that he did not consider it a matter of principle and would support whichever constitutional arrangement was likeliest to produce social justice. (He was also willing to support an independent Northern Ireland if this proved generally acceptable; the maverick unionist commentator and theologically liberal protestant Roy Garland, who admired McDowell and contrasted the atheist McDowell’s faith in justice and humanity, and his commitment to the disabled and socially marginalised, with the destructive intransigence of many fundamentalist Christians, claimed that his views had some influence on the thinking of loyalists such as John McMichael (Ir. News, 21 August 2006).) McDowell was a republican in the sense of being opposed to monarchy in principle (at one point proposing the establishment of an Ulster Republican Party) rather than as a form of Irish nationalism. He accused self-described Irish republicans of irrationally regarding a 32-county Ireland as ‘a sacred goal for which human sacrifice seemed necessary’ (ibid.).

In 1982 McDowell was a founder member of the New Ireland Group (NIG), headed by the Ballymoney surgeon John Robb (a member of Seanad Éireann (1982–9)). The group was mostly made up of protestants of social reformist and anti-partitionist views (though it had some members from catholic backgrounds); it argued that Ulster protestants should realise that a long-term settlement could not be achieved on the basis of a ‘British-administered province’, even though the present will of the majority must be respected. (‘As an Ulster protestant I find something very humiliating about Ulster people having to depend on masters’ declared McDowell, lamenting a situation in which Ulster had been stripped of all power to do anything more than ‘cleaning the streets and burying the dead’ (Ir. Times, 23 June 1986).) The old British imperial order which had underpinned unionism had vanished irrevocably, and Ulster protestants/unionists should negotiate a settlement with northern nationalists and with the republic (bearing in mind that the protestant/unionist position was weakening and would weaken further over time, so that an early settlement would be more favourable than a later one). Both nationalists and unionists must realise that such a settlement could not be achieved by the mere absorption of Northern Ireland into the existing Irish republic; in order to end the cycle of violence, both states would have to dissolve into a ‘new Ireland’ constructed on the basis of radical social reform. The group held several ‘people’s conventions’ intended to bring rival political groups into dialogue and to provide a forum for discussion to compensate for the absence of an elected local assembly, in the hope of promoting an ethos of participatory communitarian democracy.

McDowell served on the NIG’s executive from 1982 until his death, holding several executive positions (including chairman of meetings, chairman and vice-chairman); he was its most articulate spokesperson and denouncer of political apathy (some critics thought his bright ideas about the Ulster situation were more numerous than practical) and its most prominent member after Robb. Numerous NIG press statements were issued jointly by Robb and McDowell on such matters as the 1995 frameworks document, disputes over political marches, condemnations of attempted political assassinations, and calls for Sinn Féin to be included in talks without IRA arms decommissioning in order to keep the peace process alive.

McDowell reflected a distinctive northern radical tradition and a motley body of civil society groups and activists who during the Northern Ireland troubles sought to open contacts between the warring factions, consider new approaches to politics, and offer non-sectarian solutions.

In the early 1990s McDowell suffered a severe stroke but doggedly rebuilt his mobility and intellectual capacity through therapy. As elected chairman of the convocation of graduates of QUB, he was widely praised for his handling of alumni discontent at the university authorities’ decision (1994–5) to end the practice of playing ‘God save the queen’ at graduation ceremonies. He remained active to the last, opposing British intervention in Iraq in 2003, and dying suddenly in Belfast on 14 August 2006 shortly after meeting representatives of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions to seek support for a League Against Racism and Sectarianism which he proposed to establish in association with the NIG. He was cremated at Roselawn cemetery, Belfast, to the accompaniment of Dvořák’s ‘New World’ symphony and the left-wing anthem ‘The Internationale’. McDowell reflected a distinctive northern radical tradition and a motley body of civil society groups and activists who during the Northern Ireland troubles sought to open contacts between the warring factions, consider new approaches to politics, and offer non-sectarian solutions. He and his wife Jean had two sons and three daughters.

Ir. Times, 18 Aug. 1953; 22 Feb. 1969; 17 Sept. 1982; 14, 23 June 1986; 24 Feb., 28 Mar., 28 June 1995; 19 Feb., 30 Dec. 1996; 30 Jan. 1997; 9 Oct. 2006; Northern Whig, 23 Oct. 1956; Belfast Telegraph, 9 Oct. 1959; 16, 17 Aug. 2006; Ulster Herald, 27 Sept. 1997; Ir. News, 21, 22 Aug. 2006

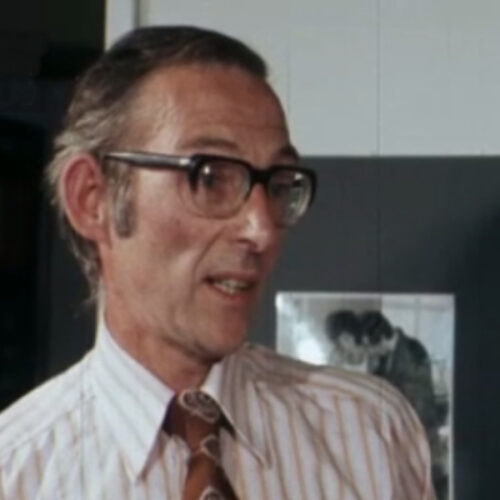

Main image: Still from BBC Rewind – Exhibition by Jordanstown school for deaf children – Gillian Chambers reports and interviews Vice-Principal Mr Jack McDowell.

We must grow out of the crude and unreal ideas of immortality and content ourselves with the only kind of […]

William Pirrie Barbour was a classicist, codebreaker, teacher, and activist. A rationalist and humanist, Barbour championed integrated education in his […]

I felt flattered by the remark of a hostile journalist that I was “a compendium of the cranks,” by which […]

This article appeared in The Secular Chronicle (Vol. V, No. 1), 2 January 1876. It marked the first issue edited […]