If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, it is time we got rid of Him.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963)

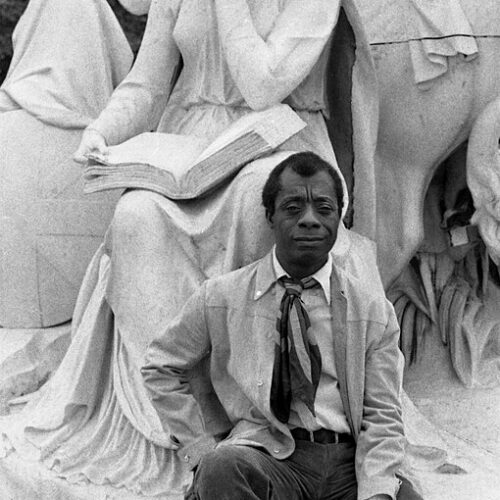

James Baldwin was a Harlem-born novelist, essayist, activist, and humanist, who spent much of his life abroad—having fled the racism and homophobia he experienced on his native soil. As well as the novels and essays which would make him one of America’s most revered writers, Baldwin took a prominent role in the civil rights movement, becoming internationally known for his resistance to oppression in all its forms. Described by the poet Gwendolyn Brooks as ‘love personified’, Baldwin’s belief in our responsibility as human beings to one another animated his life, and he was an influential opponent of all of those prejudices – whether on grounds of race, class, sex, or sexuality – which kept us apart. ‘We are a part of each other’, he wrote: ‘Many of my countrymen appear to find this fact exceedingly inconvenient and even unfair, and so, very often, do I. But none of us can do anything about it.’

Described as a ‘revolutionary humanist’, Baldwin believed that the power to change the world was in human hands: ‘We made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over’.

One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963)

Raised by his mother and strict preacher stepfather, as a youth Baldwin preached in a Pentecostal church, but came to reject religion in favour of a richly lived humanism. He wrote of being able to date ‘the slow crumbling of my faith… from the time, about a year after I had begun to preach, when I began to read again.’

Baldwin saw an immense power and possibility in humankind, if only people were willing to meet reality with open eyes. This meant an honest evaluation of history, and an active willingness to address the problems of the present day in order to reshape the world. ‘I know that people can be better than they are,’ he wrote:

We are capable of bearing a great burden, once we discover that the burden is reality and arrive where reality is.

After all:

One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.

Baldwin criticised the role of the Church in contributing to oppression, and resented the hypocrisy he saw in the behaviour of many professed Christians. In The Fire Next Time he wrote:

I was also able to see that the principles governing the rites and customs of the churches in which I grew up did not differ from the principles governing the rites and customs of other churches, white. The principles were Blindness, Loneliness, and Terror, the first principle necessarily and actively cultivated in order to deny the two others. I would love to believe that the principles were Faith, Hope, and Charity, but this is clearly not so for most Christians, or for what we call the Christian world.

Although he left America for France at 24, Baldwin became a powerful voice in challenging national myths and standing for genuine equality. He took part in 1963’s March on Washington in 1963 and 1965’s Selma to Montgomery march, and wrote, lectured, and organised for civil rights.

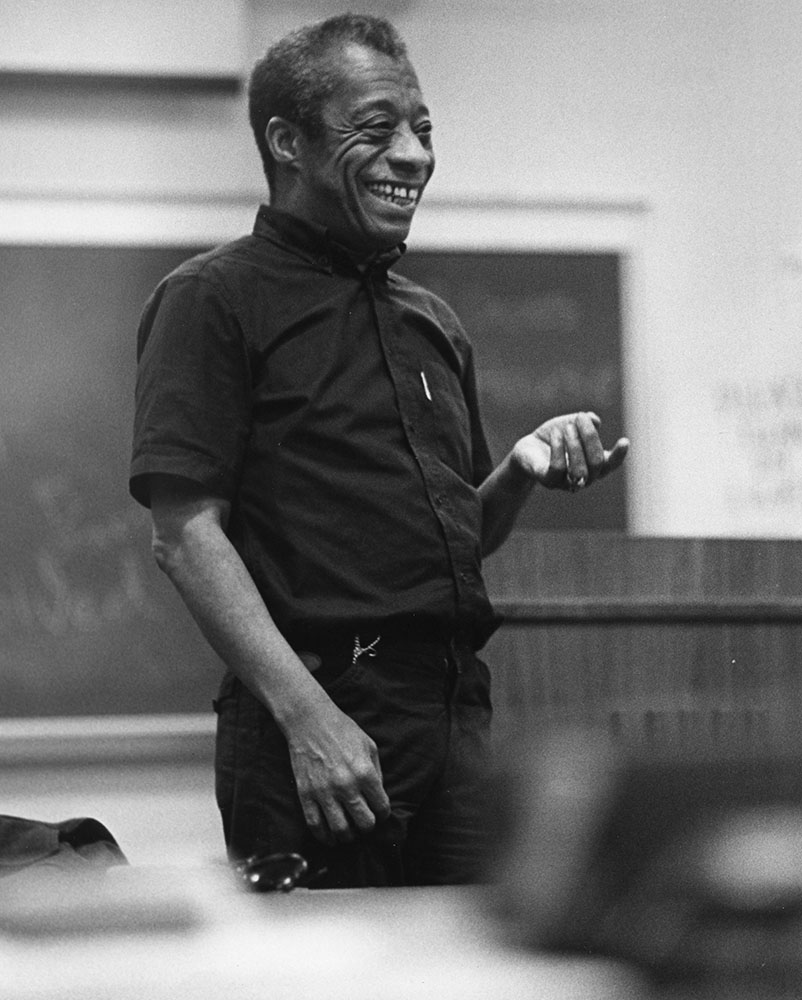

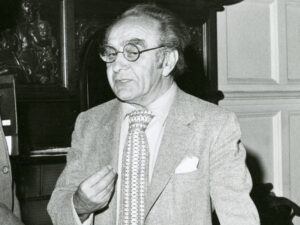

On 18 February 1965, James Baldwin spoke at the Cambridge University Union on the motion ‘The American Dream is at the Expense of the American Negro’, concluding to a rare standing ovation. His opponent was the conservative writer and broadcaster William F. Buckley Jr., who supported the policies of racial segregation then still extant in the southern United States. Baldwin had left America in his 20s, spending many years in Europe, and spoke from bitter experience about the prejudice and bigotry he had experienced on his native soil. After the debate, Baldwin dined with the Cambridge Humanists.

Reviewing I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary about James Baldwin which drew on the Cambridge debate, American humanist Sincere Kirabo described the resonance Baldwin’s words and writings continue to have today. He suggested that:

Baldwin’s poetic potency proves timeless as it continues to enter our core, cozy up to our beliefs, confront harmful opinions we have of the world and others, and demand a more just reckoning.

Sincere Kirabo, ‘Film Review: I Am Not Your Negro‘ for The Humanist, 8 February 2017

You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read. It was books that taught me, the things that tormented me the most were the very things that connected me to all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.

James Baldwin, Television Narrative about his life, WNEW-TV, New York City, 1 June 1964

Baldwin’s writing and activism raised public awareness regarding racial and sexual oppression. His novels feature African American gay and bisexual men, such as Giovanni’s Room (1956) in which a black bisexual man living in Paris (like Baldwin at the time) meets an Italian bartender called Giovanni at a gay bar, following which a tumultuous love affair ensues. The manuscript was rejected by many publishers who warned this could detrimentally affect Baldwin’s career. Eventually, the novel was published in 1956 and has gone on to become not only one of Baldwin’s most famous works but also one of the foundational texts of LGBT literature.

Baldwin was a firm believer that gender and sexuality was fluid and should not be divided by strict categories. In his 1985 article for Playboy, he reflected on his experience of gender and critiqued how the American ideal of manhood posed gender nonconforming people as a newfound unnatural phenomenon:

The present androgynous ‘craze’ — to underestimate it — strikes me as an attempt to be honest concerning one’s nature.

10 questions about the life of James Baldwin | National Museum of African American History and Culture

… in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to […]

The notion that a man shall judge for himself what he is told, sifting the evidence and weighing the conclusions, […]

Indian social and religious reformer Rammohun Roy is sometimes referred to as the ‘father of modern India’: a progressive thinker, […]

From the outset IAS aimed to have an open approach to prospective adopters irrespective of their race, religion and creed, […]