The difference and variety of our human family more and more seems to me to be a wise provision that has come out of nature. The varied faces of people in the world hold something good for each other… Our coming together is a challenge and a hope for all.

James Berry, Introduction to Windrush Songs (2007)

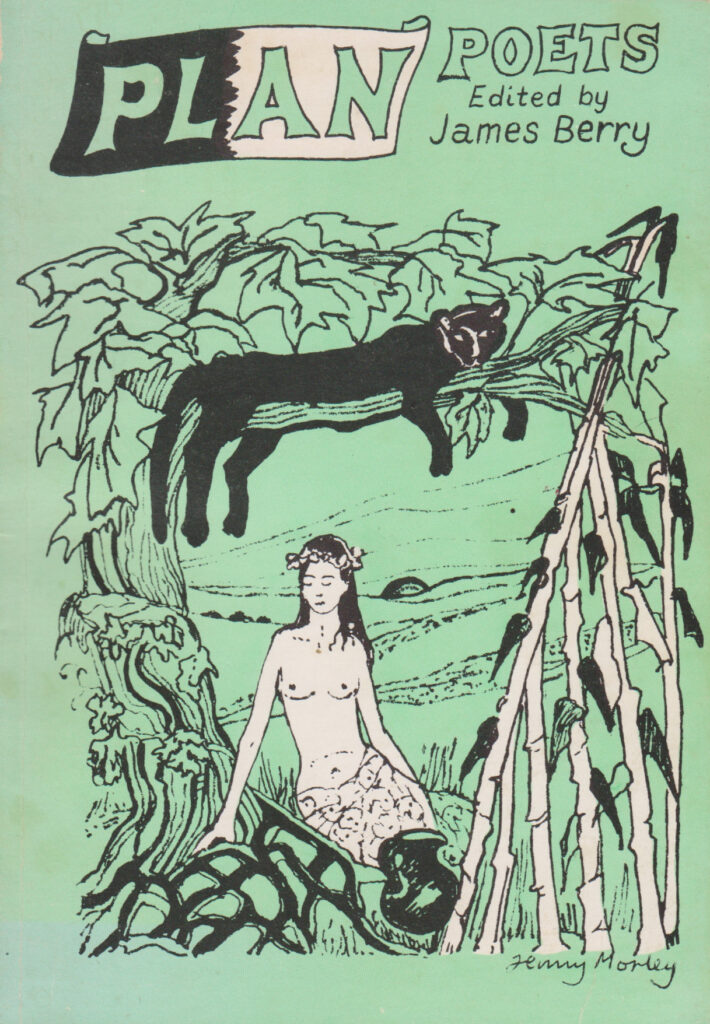

James Berry was an award-winning Jamaican-born poet who played a significant role in popularising West Indian poetry in the UK, including as part of the Caribbean Artists’ Movement (CAM). Though it is frequently omitted from his bibliography, Berry edited the 1982 collection PLAN Poets, an anthology of poems by members of the humanist Progressive League, of which Berry himself was a member. In his own poetry, Berry emphasized values of compassion, cooperation, and the celebration of life, but did not shy away from confronting the racism and injustices he experienced in Britain and America. Described in his Guardian obituary as ‘a determined though unsentimental advocate of friendship between races’, Berry worked tirelessly to celebrate diversity while encouraging togetherness.

In the land and sea culture-crossed

James Berry, ‘In the Land and Sea Culture-crossed’ in Windrush Songs (2007)

we call to the hearts of difference.

Restless, we widen our boundaries.

Expansion may be for self-loving, yet

our world is smaller and closer

and, in gesturing, we touch different other.

James Berry was born in Portland, Jamaica, the son of Robert Berry (a smallholder and fisherman) and Maud (a seamstress). He received an elementary education, but was a bright and creative child, reading aloud for others and inventing his own tales. When he made the decision to leave Jamaica in search of work, further education was a driver nearly as important as employment prospects. Much of his later poetry and writings celebrated the beauty of his native country and the richness of its culture, enlivened by the Jamaican patois Berry wove through his works.

In an introduction to his collection Windrush Songs (2007), Berry explained the impulse which sent him from Jamaica to England. The Caribbean at that time, he wrote, ‘was suffering from its history’, and Berry’s generation felt themselves having graduated elementary school without hope of further education or employment: ‘stranded, with an overwhelming sense of waste’. ‘Here we were,’ Berry recalled, ‘hating the place we loved, because it was on the verge of choking us to death’. He could not afford to travel on the first ship that arrived in 1948, the Windrush – which gave its name to a generation of people called on to help rebuild post-war Britain – but saved enough to embark on the second, the SS Orbita, in October that year. Six years earlier, in 1942, Berry had travelled to the United States seeking similar opportunities, but his experience of entrenched racism confirmed his impression that ‘America was not a free place for black people.’ Travelling to England, in hopes of work and continuing education, Berry described the hope he and his fellow travellers shared of ‘the possibility of a new way of life, a democratic way of life, in which we would be equal human beings.’

‘Stirred by restlessness, pushed by history,

I found myself in the centre of Empire’.

In Windrush Songs, Berry wrote of ‘goin to Englan to speed up / what Empire start – that scorn, self-love and pride, I will / put together with humility.’ In these poems, an awareness of history is wedded to a humanising hope: ‘Man – I goin to Englan / to help speed up Englan / into a greater oneness / with an ever growing humanity’. Once in England, Berry began work for the Post Office, continuing to write and immersing himself in the Caribbean community of Brixton. Taking early retirement in 1977 to focus on writing, Berry progressively sought to realise this vision of a ‘greater oneness’ in his literary work – becoming a major force in amplifying the voices of black British writers – and through outreach, acutely aware of the need for multicultural education in an increasingly diverse Britain.

In 1976, Berry edited Bluefoot Traveller, a seminal collection of poems by West Indian writers living in Britain. The title poem, ‘Bluefoot Traveller’, drew on the Jamaican term ‘bluefoot’, suggesting an outsider or wanderer. His first full poetry collection was Fractured Circles, published in 1979, and in 1981 he became the first Caribbean writer to win the Poetry Society’s National Poetry Competition. The following year, he edited PLAN Poets, a poetry anthology marking 50 years of the Progressive League, of which Berry was a member. Characteristically, his introduction highlighted the communal effort of editing. ‘Take it,’ he wrote, ‘the word ‘shared’ is most operative here’. Three of Berry’s own poems appeared in the collection, and he was involved in events at Conway Hall, and for the Progressive League.

Berry’s second published collection was Lucy’s Letters and Loving (1982), poems in the persona of a Jamaican woman in Britain, and was followed by others including Chain of Days (1985), Hot Cold Earth (1995), and Windrush Songs (2007). He also published a second anthology of poems by black writers, 1984’s News for Babylon. Berry also wrote poems and stories for young people, winning the Smarties prize for children’s writing in 1987. He worked in schools, gave regular public readings, and worked alongside other black writers – including John La Rose and Andrew Salkey – to promote Caribbean literature, culture, and community.

Though some of Berry’s poems borrowed the language of religion, their praise remained explicitly earthly. In ‘Hymn to New Day Arriving’, Berry wrote: ‘New day is turned-over book page, / new day renews spirit of energy. / Just like a little fresh cool breeze / new day invigorates with new life/ … Oh how everything has its moment, its voice, its ending – / it is overwhelming.’ In ‘Benediction’, in place of divine praise, Berry’s thanks were to ‘the ear,’ ‘to feeling’, ‘to touch’, and finally ‘to flowering of white moon / and spreading shawl of black night / holding villages and cities together’. Human togetherness and the beauty of nature are awe-inspiring enough. They reflect, as Berry wrote in his Windrush Songs introduction, his ‘love of nature and of human nature… a personal celebration of the wonder of being’. In ‘Learning Beauty’, through ‘Watching the joy of embraces / in the thrill of voices / I learn the beauty of tenderness.’ And in ‘Wash of Sunlight’:

I marvel at the burst of seeds to sunlight

and the careless giving of water over rocks…

I stand on the land. I touch

fire, touch water, feel air.

These poems are richly humanist in their celebration of what it means to be human, bearing witness to the world, and glorying in its beauty. Berry did touch on religious stories, such as in Celebration Song (1994), about the birth of Jesus, though the emphasis rested on the joy of new life and the relationship between mother and child. In other books for children, Berry retold tales from West Indian and African folklore, like the stories of Anancy, capable of being ‘anything from a lovable rogue to an artful prince,’ reliant on his wits alone to survive. In 1990, Berry was awarded an OBE for his services to poetry, and in 2002 an honorary degree from the Open University.

During the last years of his life, Berry suffered with dementia but continued – with help – to create poetry. A benefit held in 2013 to support his care celebrated Berry’s rich contribution to literature in Britain, and his pivotal role in giving voice to the colonised, marginalised, and ‘othered’. Through his own embrace of dialect (or ‘Nation Language’) and celebration of Caribbean culture, Berry had inspired subsequent generations of writers, and helped to change the landscape of British poetry. He died in a West London nursing home on 20 June 2017.

A Voice in me says:

James Berry, ‘In the Land and Sea Culture-crossed’ in Windrush Songs (2007)

We will change wildness to love,

into rejuvenation.

There is madness in self-love

we will change it to sanity.

We will release change in each other.

James Berry was an influential and much loved poet, and a pioneering figure in the promotion of black British voices. Though his involvement with the Progressive League has often been overlooked, it suggests another aspect of Berry’s drive to work for change, including through creativity, collaboration, and dialogue. In his body of work, humanists today can find much to inspire – from vivid depictions of the natural world and human possibility, to an unflinching realism with regards to social ills and the need for change. As Fanny Cockerell, editor of PLAN magazine wrote to the Ethical Record following the publication of the League’s anthology: ‘Man cannot live by logic alone’.

James Berry | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

James Berry | British Council of Literature

‘The poet James Berry’ | Black History Month

Obituaries in The Guardian and Independent

James Berry Archive | British Library

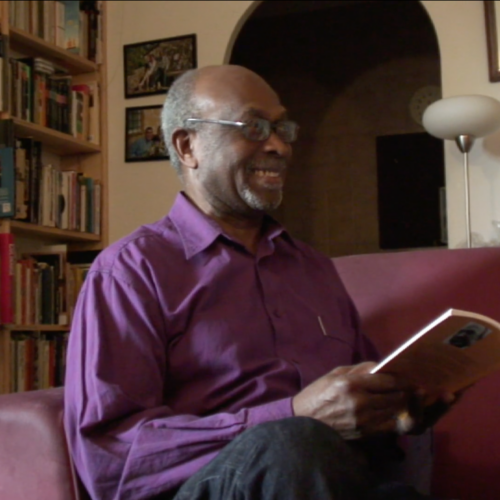

Main image: Still of James Berry from a recording made by Pamela Robertson-Pearce in June 2007 for Bloodaxe Books’ anthology, In Person: 30 Poets (2008).

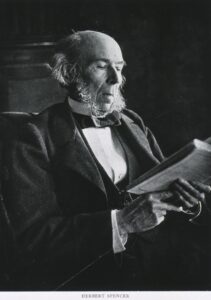

No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; […]

Kensal Green, opened in 1833, was London’s first commercial cemetery, and the originator of the city’s ‘Magnificent Seven’. These suburban […]

We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done. Alan […]

If any delegate present thinks that the Fabian Society was wise from the hour of its birth, let him forthwith […]