The moral value of a belief in eternal life is a doubtful matter. But this is certain, that where rest is to [be] found, it is for those who have earned it, not by prayer and fasting, but by work… Our work is a work of love, not a task for reward.

James Ramsay MacDonald, ‘Essay on Religion’ (unpublished manuscript, c. 1900-10)

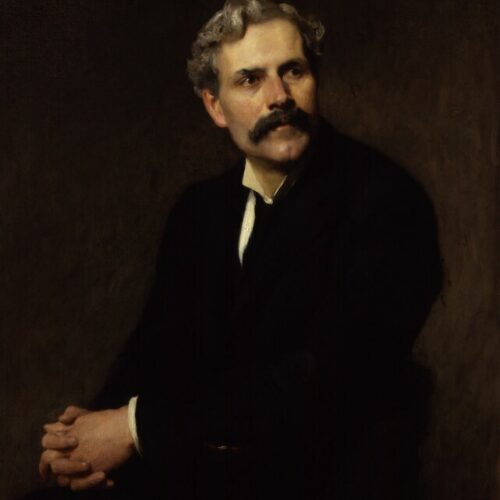

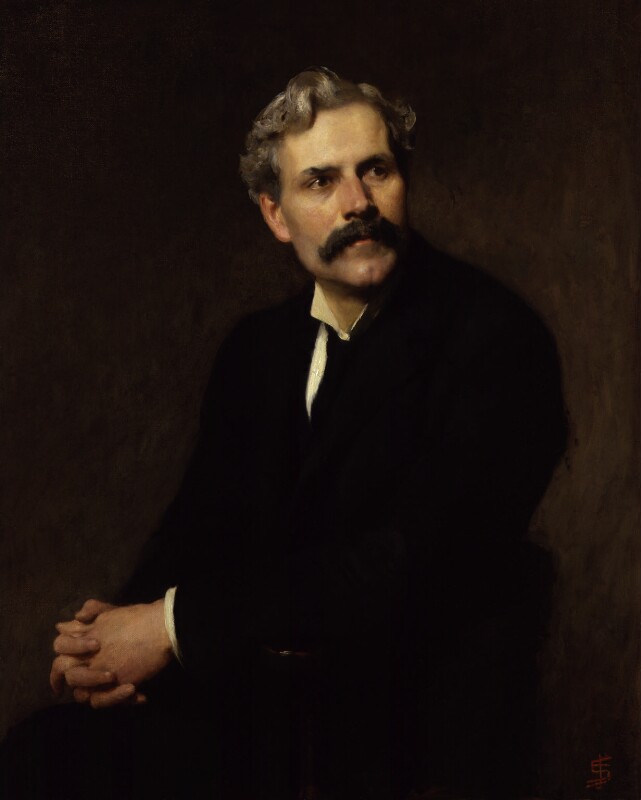

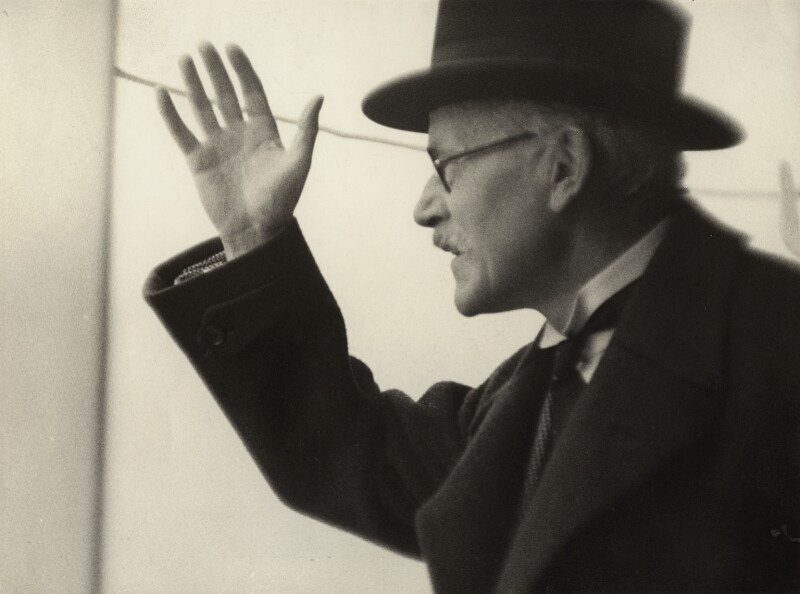

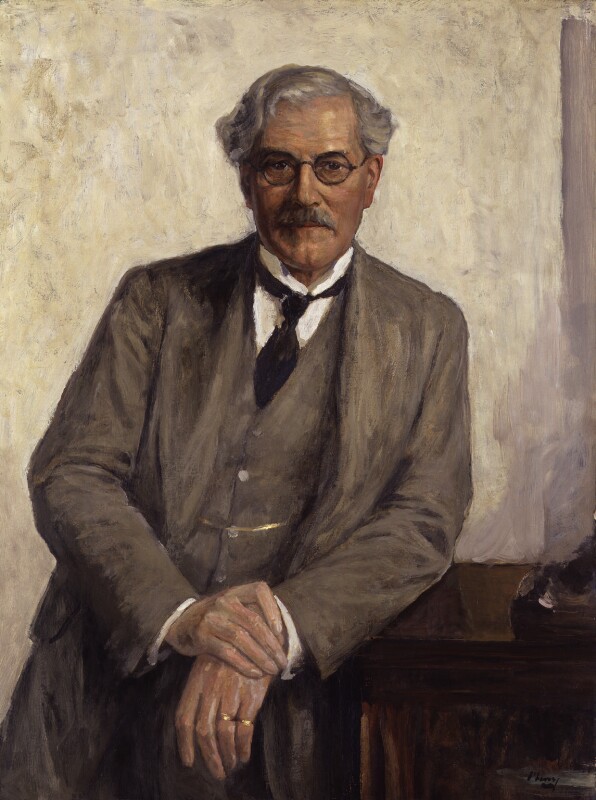

James Ramsay MacDonald was the first Labour Prime Minister of Great Britain, and an early, and active, member of the Ethical movement. A socialist, MacDonald believed in putting reason and compassion to work for reform, seeking equal opportunity and a fairer society. MacDonald dismissed doctrinal religion, finding a home in the early humanist movement which emphasised an applied ethical system, without reference to supernatural ideals. He became a regular contributor to Stanton Coit’s paper, the Ethical World, chaired several important congresses of the Union of Ethical Societies (today’s Humanists UK), and advocated for secular education in schools.

James Ramsay MacDonald was born in Lossiemouth, Scotland, the illegitimate son of Anne Ramsay and John MacDonald, both farm workers. Raised by his mother and grandmother, MacDonald was educated first at a Free Church of Scotland school, and subsequently at the local parish school, Drainie. On leaving, he worked briefly as a farm labourer until – at the age of 15 – he was appointed back at Drainie as a pupil teacher, where he remained for four years of marked personal and intellectual growth. A passionate reader, he was also an enthusiastic scientist, founding a field studies club at the school for excursions and discussion. Macdonald would later write gratefully of the teacher there as being among those ‘who teach without putting any goal except knowledge before their pupils, and who present knowledge to them as something which is pursued through a man’s life’. This sat in stark contrast to the religiously devout, and harshly disciplinarian, schoolmaster of his earliest years.

MacDonald was also actively involved in the Mutual Improvement Society, growing familiar with debate. Surviving papers from his speeches to the group testify to his emerging political aspirations, as well as to his philosophical musings. One 1883 speech describes the prevalence and danger of superstition: a ‘great power damming back the flood of social progress and scientific research’. MacDonald left Lossiemouth in 1885, to take up a post in Bristol as assistant to a clergyman. There, within a thriving radical and socialist scene, he joined the Bristol Social Democrats. The following year, he went to London, remaining active in the socialist movement, and taking up evening classes at Birkbeck College.

In London, MacDonald became actively involved in two causes which placed moral action at their heart: the socialist Fellowship of the New Life (which gave rise to the Fabian Society), and the burgeoning Ethical movement. In an article for Seedtime, the Fellowship’s journal, MacDonald outlined his central belief: that ‘political change is not desirable for its own sake, but rather for its effect on human well-being’. The ethical societies, which had – as the London Ethical Society put it – ‘well-doing and well-being’ as their object, drew those like MacDonald, who sought social reform in the service of human welfare. From the late 1880s, he attended ‘services’ at the South Place Ethical Society, lectured for the East London Ethical Society, and became ever more involved in this secular striving for a fairer world.

MacDonald was a founding member of Stanton Coit’s Society of Ethical Propagandists, a group formed in 1898 to promote the Ethical movement. Their working principle was that:

…a good life is desirable for its own sake, and rests upon no supernatural sanction. The organic nature of human society implies that a good individual life can only be attained in a good society.

Thus, the twin aims of social reform and self-improvement. Other propagandists included Harry Snell and William Sanders, who were, like MacDonald, leading figures in the Ethical movement, and Labour Party politicians. MacDonald’s biographers have noted the appeal of the Ethical movement to men like these, and to MacDonald in particular, who David Marquand describes as having had both ‘a longing for an exalted communion of feeling’ and ’a revulsion from sharp doctrinal precision’. Lord Godfrey Elton observed that MacDonald ‘was not prepared to accept the dogma of any formal church, and… believed at this time that a secular ethical society might be more active in social reform than any religious organisation.’ A regular contributor to the movement’s journal the Ethical World, and chair of more than one of the Union of Ethical Societies’ Annual Congresses, the Ethical movement was undoubtedly more central to the development of MacDonald’s social and political ideals than is often assumed.

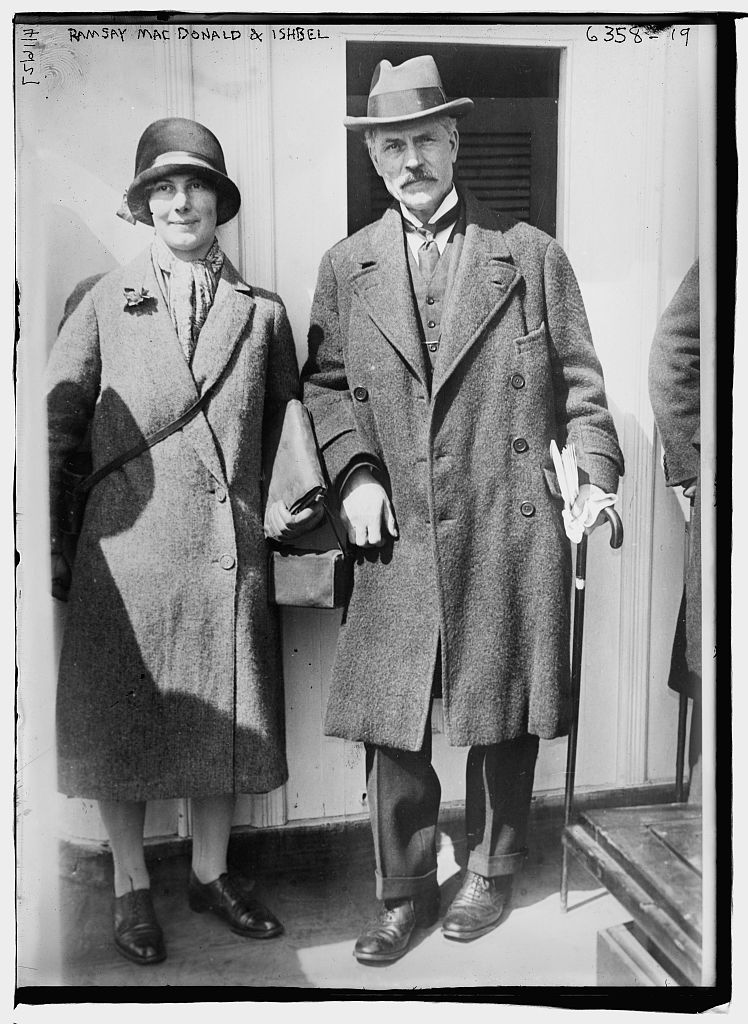

MacDonald worked for three years as an assistant to a Liberal candidate, joining the Independent Labour Party in 1893, and working as a journalist. He rose quickly through the party’s ranks, eventually becoming its leader. In 1924, Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister, leading Britain’s first ever Labour government. In addition to this historic precedent was another: MacDonald’s appointment of Margaret Bondfield, the first woman made a government minister. Though his first term as the country’s leader lasted less than a year, MacDonald became Prime Minister for a second time in 1929. Notable measures introduced under his government, 1929-1935, included the 1934 Unemployment Act, and the Special Areas Act, both of which responded to high levels of interwar unemployment. MacDonald left government in May 1937, and turned down the offer of a peerage from King George VI, Stanley Baldwin, and Neville Chamberlain.

James Ramsay MacDonald died on 9 November 1937, during a trip to South America with his daughter, Sheila. He was given a public funeral in Westminster Abbey and a private service at Golders Green Crematorium.

An understanding of James Ramsay MacDonald is illuminated by a view of his moral ideals, exemplified by his early involvement in the Ethical movement. MacDonald was motivated by a keen desire to effect change for the good of others, to create a more equal society in service of human flourishing, and to find fellowship in the pursuit of ethical ideals. Like many others of his generation, unable to subscribe to the doctrines of religion but devoted nonetheless to living well with others, he was drawn to the humanist movement. Paraphrasing Stanton Coit, with whom MacDonald worked closely for the Ethical movement, Lord Elton wrote:

Perhaps the truth about MacDonald’s ambition is best expressed by saying that there are some men who neither desire nor expect to achieve special distinction or power, some who are determined, come what may, to achieve power for its own sake, and some who desire it, but desire it chiefly in order that they may use it for what they believe to be good ends. MacDonald belonged to this last category.

His was a humanist vision of cooperation, compassion, and conviction. After being elected Prime Minister, MacDonald rarely spoke directly on religious issues, but his secularist and humanist commitments were evident in his speeches against compulsory religious instruction in schools, echoing his earlier campaigning alongside colleagues in the Moral Instruction League.

Humanism involves not just the deletion of God from moral thought, but the development of humanity on a rational and […]

…the smallest experience is sufficient to convince that it is more pleasing, to be at peace than at enmity with […]

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington was an activist, feminist, and humanist, who founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League, and was described by the […]

Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to […]