Essentially, I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life. Whether there is such a thing as a soul, or whether there is a survival after death or not, I do not know; and, important as these questions are, they do not trouble me in the least.

Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India (1946)

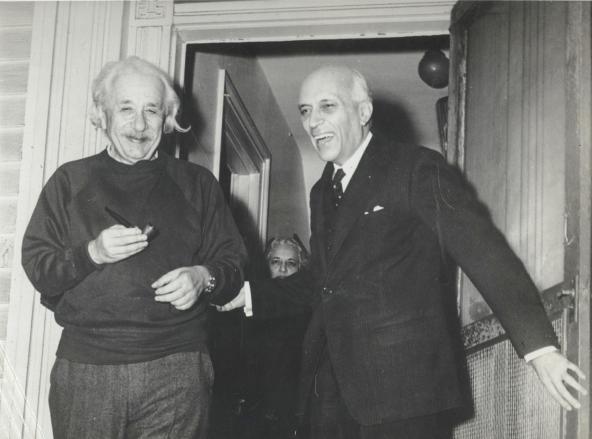

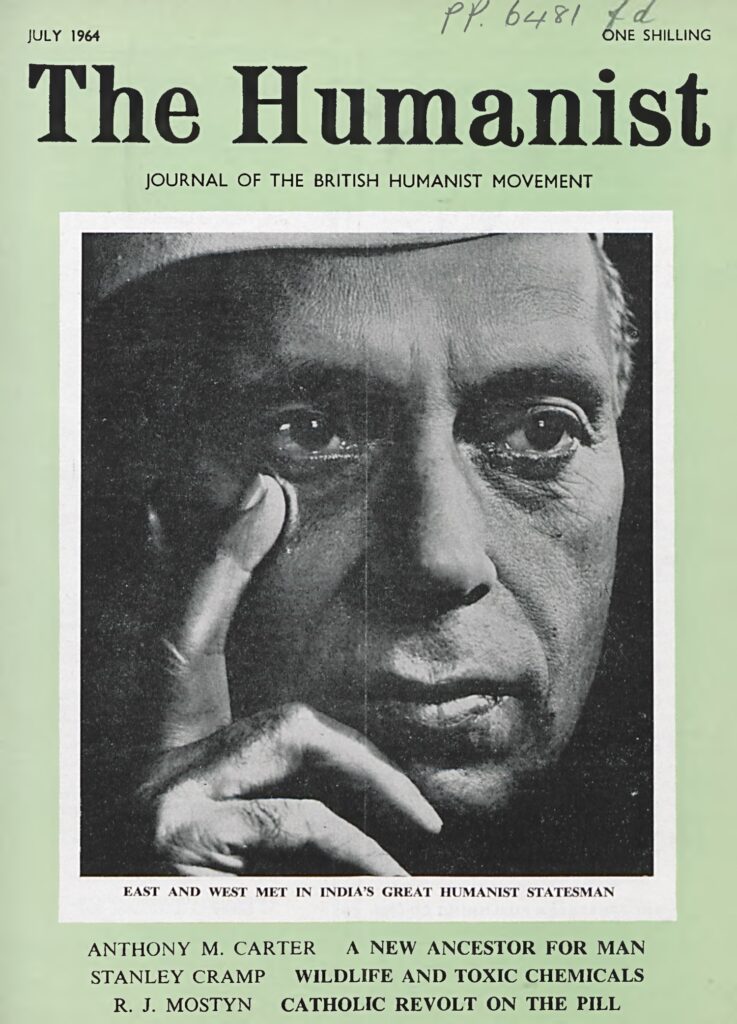

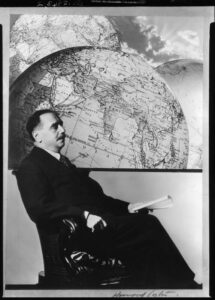

Jawaharlal Nehru was an influential Indian nationalist leader, politician, and statesman who played a pivotal role in the country’s struggle for independence from British rule. Born into a prominent political family, Nehru was educated in England. On his return to India, he became deeply involved in the Indian National Congress, the leading political party fighting for independence. Nehru became the first Prime Minister of independent India in 1947, serving until his death in 1964. A humanist and secularist, Nehru’s vision for India was marked by a commitment to secularism, democracy, and social justice.

Why should we trouble ourselves about matters beyond our ken when the problems of the world insistently demand solution?

Jawaharlal Nehru, Address to the National Academy of Sciences, 5 March 1938

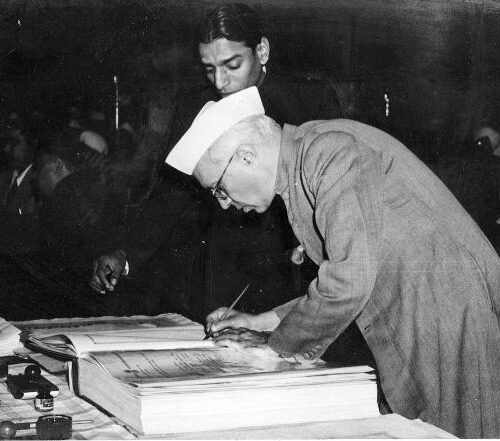

Born on 14 November 1889, in Allahabad (now Prayagraj), India, Jawaharlal Nehru was part of a prominent political family. His father, Motilal Nehru, was a respected lawyer and a key figure in the Indian National Congress. One of Jawaharlal’s sisters, Vijaya Lakshmi, later became the first female president of the United Nations General Assembly.

Jawaharlal was educated in England at Harrow, and later at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied natural sciences. Here, Nehru was exposed to Western political thought and continued to develop a strong nationalist consciousness. He trained in law, and was called to the bar in 1912. That year, he returned to India, but was unenthused by a career in law. He joined the Indian National Congress, becoming an active participant in the fight against British colonial rule.

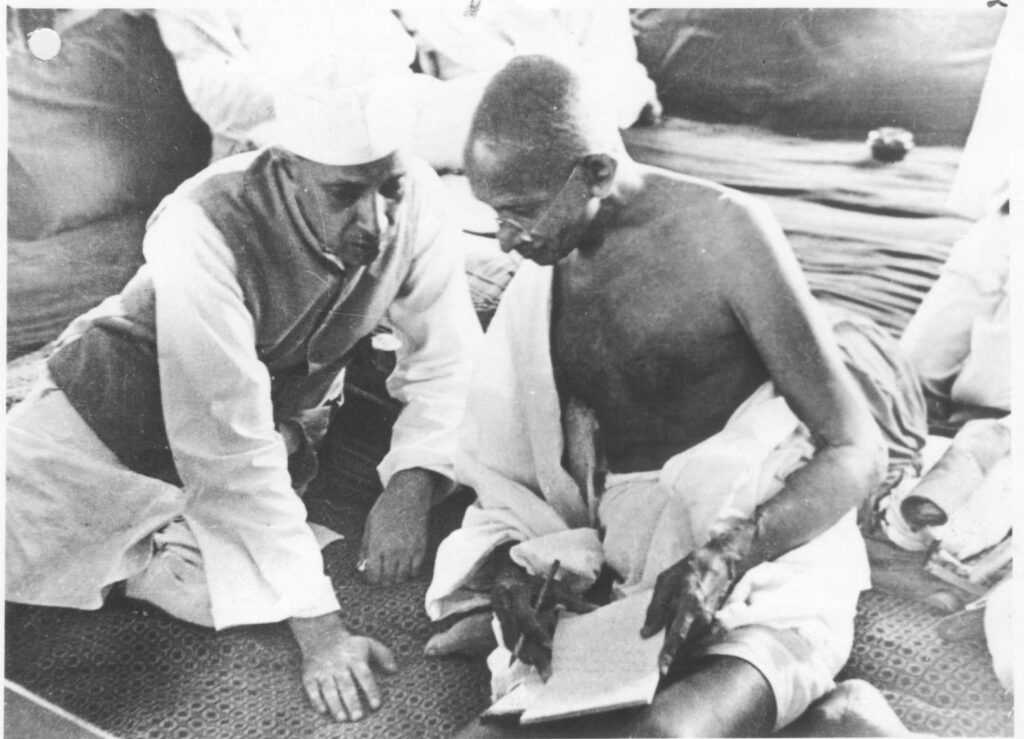

A close associate of Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru became committed to nonviolent civil disobedience, and was imprisoned nine times during the 1930s and 1940s. Between 1934–5, while in gaol, Nehru penned an autobiography – ‘in a mood of self-questioning’ – which outlined many of his views on organised religion, alongside exploring his personal and political development.

Influenced by his scientific learning, and through the observation of religious ideas exploited and misused, he wrote of his inability to find comfort in the supposed sureties of religion:

I am afraid it is impossible for me to seek harbourage in this way. I prefer the open sea, with all its storms and tempests. Nor am I greatly interested in the after life, in what happens after death. I find the problems of this life sufficiently absorbing to fill my mind…

In the same work, Nehru expressed his distaste for the pursuit of religious salvation or spiritual growth in lieu of practical work for humanity. Echoing the secularist freethinkers of the 19th century, he wrote:

…the usual religious outlook does not concern itself with this world. It seems to me to be the enemy of clear thought, for it is based not only on the acceptance without demur of certain fixed and unalterable theories and dogmas, but also on sentiment and emotion and passion… And organised religion invariably becomes a vested interest and thus inevitably a reactionary force opposing change and progress.

Jawaharlal Nehru, ‘What is Religion’ in An Autobiography (1936)

Starting from the assumption of having discovered ‘truth’, Nehru wrote, religion too often ‘deliberately shut its eyes to reality for fear that this might not fit in’ with its doctrines, more concerned with communicating dogma than pursuing social justice. In contrast, Nehru felt pressingly the need for independence and reform.

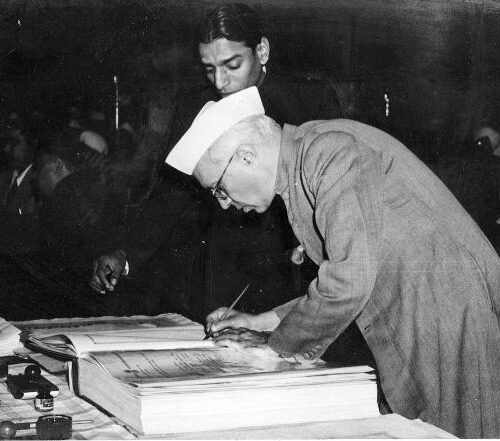

The year 1942 marked a turning point in India’s struggle for freedom with the Quit India Movement, and Nehru, along with other leaders, was once again imprisoned by the British. However, India’s journey towards independence accelerated, and in 1947 the country finally gained freedom, with Nehru playing a significant role in the preceding negotiations. On 15 August 1947, Nehru became independent India’s first Prime Minister. His leadership was marked by a commitment to democracy, secularism, and social justice. Nehru played a crucial role in drafting the Indian Constitution, which enshrined principles of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, and prohibited discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, or place of birth.

For Nehru, secularism – which would keep religious beliefs separate from the affairs of the State, and enable pluralism and tolerance – was the solution to:

political conflict between those who wanted a free, united, and democratic India and certain reactionary and feudal elements who, under the guise of religion, wanted to preserve their special interests. Religion, as practiced and exploited in this way by its votaries of different creeds, seemed to me a curse and a barrier to all progress, social and individual. Religion, which was supposed to encourage spirituality and brotherly feeling, became the fountainhead of hatred, narrowness, meanness, and the lowest materialism.

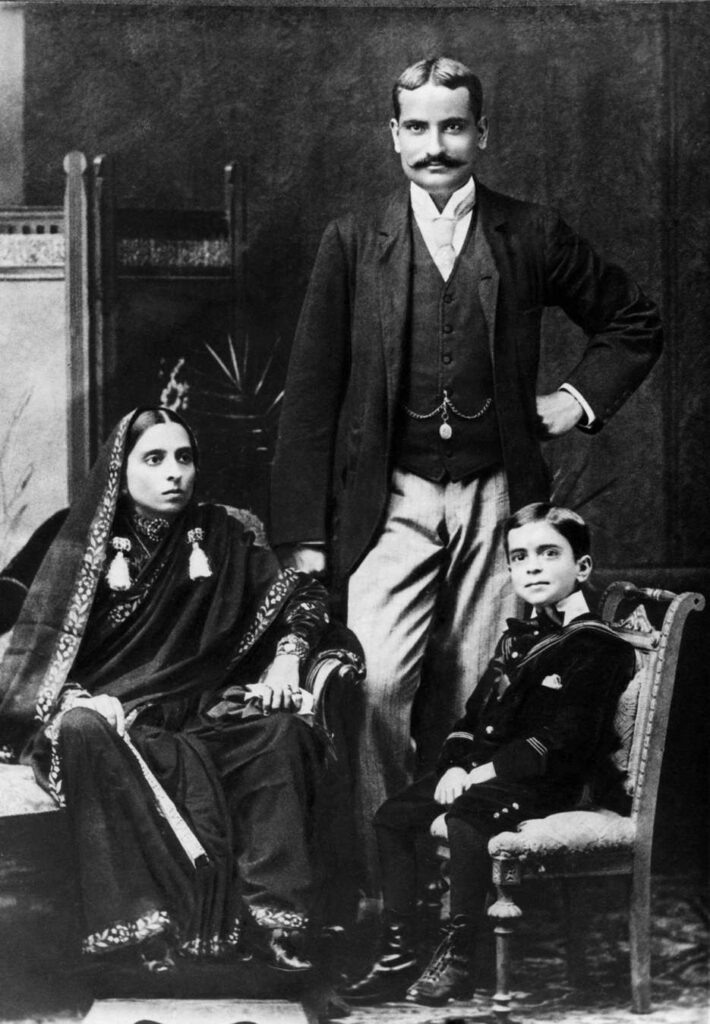

As a statesman, Nehru’s vision was one of economic development and secular democracy. His emphasis on education and scientific temper was reflected in the establishment of institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs). Committed to providing free and compulsory primary education to India’s children, he oversaw the creation of new schools and rural enrolment programmes. During the Cold War, Nehru was a proponent of non-alignment, advocating for a foreign policy independent of the superpower blocs. He played a crucial role in the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement, promoting peace and cooperation among developing nations.

Jawaharlal Nehru died on 27 May 1964, remembered as the architect of modern India. At a memorial service held in New York, the United Nations’ C.V. Narasimhan praised Nehru for his ‘faith in the human spirit… belief in the concept of the secular state… and faith in the concept of peaceful change’.

I wish to declare with all earnestness that I do not want any religious ceremonies performed for me after my death. I do not believe in any such ceremonies and to submit to them, even as a matter of form, would be hypocrisy and an attempt to delude ourselves and others.

last will and testament of Prime Minister Nehru, 21 June 1954

Nehru’s vision for India was marked by a commitment to secularism, democracy, and social justice. As a humanist and secularist, he championed the idea of a pluralistic and inclusive society where people of all religions and backgrounds could coexist harmoniously. Nehru firmly believed in the separation of religion from the affairs of the state, advocating for a modern, scientific, and rational approach to governance. His efforts in shaping India’s constitution reflected these principles, laying the foundation for a secular and democratic nation. Nehru’s legacy as a statesman and his contributions to India’s political and social fabric continue to be celebrated, and he is regularly cited as one of the country’s most significant historical figures.

Jawaharlal Nehru, Toward Freedom: An Autobiography

Constitution of India | Library of Congress

One might say that since retirement I have been reworking my paradigm. In that reworking I have reached conclusions, but […]

A cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant […]

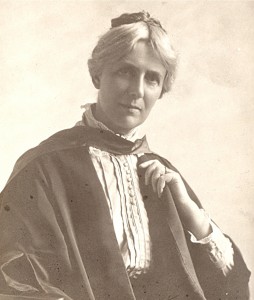

Mackenzie Hall is a community space in the village of Brockweir, Gloucestershire, given by Millicent Mackenzie in memory of her […]

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]