It is impossible that Theology can throw any light upon either morality or jurisprudence.

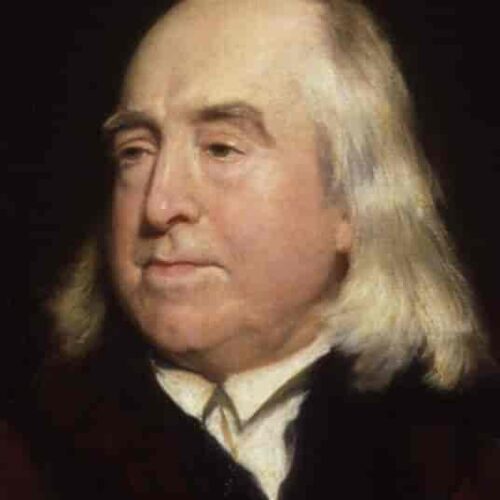

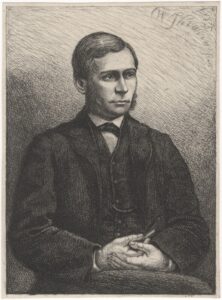

Jeremy Bentham

Philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham is widely regarded as the originator of utilitarianism: the theory that the right course of action is one which produces ‘the greatest happiness of the greatest number’. He was a passionate social reformer, advocating for legal and prison reform, as well as for universal suffrage and the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Bentham argued for religious freedom, and believed in the complete separation of church and state. Frequently referred to as the ‘spiritual founder’ of University College London – the country’s first to admit students regardless of religious faith – Bentham played no active part in bringing the university into being. 80 years old when it opened, he was nevertheless a significant influence on its founders, and on the principles by which they worked.

Jeremy Bentham was born in Spitalfields, London, on 15 February 1748, the son of a wealthy attorney. He displayed a precocious intelligence from an early age, and initially seemed destined to follow his father into law, being sent to Queen’s College, Oxford at the age of 12. Oxford imbued Bentham with a distrust of the Anglican establishment, and a distaste for the sense of privilege and laxity he perceived as characterising the colleges. He particularly resented Oxford’s requirement of subscription to the Thirty-nine Articles (the defining statements of the Church of England), against which he wrote critically.

Bentham was called to the bar in 1769, around which period he discovered the writings of Joseph Priestley and David Hume. The young Bentham, inspired by his readings and increasingly disillusioned with legal practice, turned instead to questioning, critiquing, and seeking to reform the laws themselves. In A Fragment on Government, anonymously published in 1776, Bentham stated the belief which came to define his theory of utilitarianism: that ‘it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong’. He coined the term ‘utilitarian’ in 1781.

Bentham was a prodigious writer and thinker, whose advocacies ranged from prison reform to universal suffrage. His utilitarianism was not merely an abstract concept, but an applied philosophy against which all aspects of social, cultural, legal, and religious life could be tested. The primary responsibility of a country’s laws, as Bentham saw it, was to promote happiness among its citizens: ‘The right and proper end of government in every political community is the greatest happiness of all the individuals of which it is composed.’ He similarly believed that the role of education was to help ensure a happy life, writing that ‘the common end of every person’s education is happiness’.

Bentham championed the complete separation of church and state, believing it was impossible to have any knowledge of the supernatural, and therefore that theology had no place in deducing ‘moral duties or political regulations’. He was clear that dispensing with religious motivations in life and lawmaking did not mean the abandonment of morality or kindness, believing that human beings could – and should – exercise tolerance and compassion in law and its enforcement. With this in mind, Bentham advocated for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, the reform of prisons, and universal suffrage.

In 1823, Bentham co-founded the Westminster Review. The first article in the inaugural issue of that journal, titled ‘Men and Things’, was written by writer and reformer William Johnson Fox, a significant leader of South Place (today Conway Hall Ethical Society). In subsequent years, the Review published the best and brightest thinkers and reformers, including Bentham’s protégé John Stuart Mill, and Mill’s wife and collaborator Harriet Taylor Mill.

Jeremy Bentham died on 6 June 1832, and his body – as he willed – was publicly dissected by friend and surgeon Thomas Southwood Smith. His skeleton was preserved as an ‘auto-icon’, which remains at UCL to this day. This famous relic is Bentham’s skeleton, dressed in his clothes, with a wax head. It has been posited that he chose to have his body preserved in this way ‘as an attempt to question religious sensibilities about life and death’.

In his tireless advocacy of all manner of humane reforms, and staunch belief that morality should not be decided by religion, Jeremy Bentham was a significant proponent of humanist values. The principles of secularism he advocated, and the application of reason and compassion to matters of law and custom, remain central in humanism today.

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]

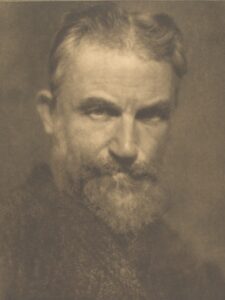

The death of Shaw is to progressive people of the twentieth century what the death of Voltaire must have been […]

As well as being home to Conway Hall and its humanist library, Red Lion Square contains statues of two prominent […]

Thomas Hill Green was a philosopher, educator, and a Liberal, whose idealist philosophy (with its practical implications) was a significant […]