…the only efficient, the only decent prayer, is Action.

John Galsworthy, ‘Philosophy of Life’ in Glimpses and Reflections (1937)

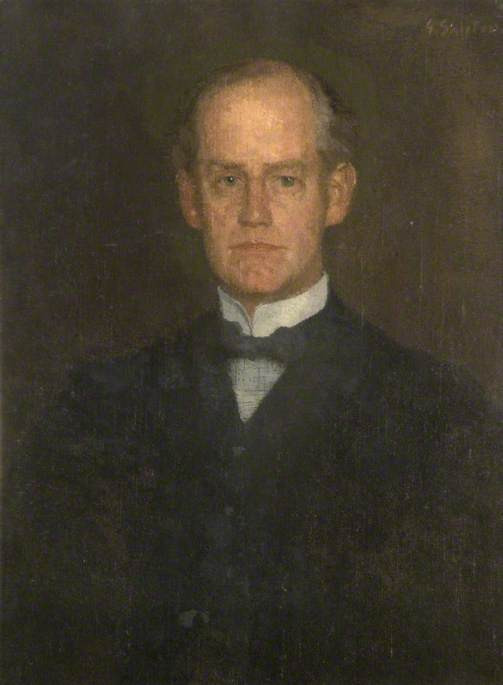

Best remembered today for The Forsyte Saga, John Galsworthy was admired during his lifetime as a playwright and humanitarian, whose own privilege he turned towards helping others. Raised in a wealthy, Anglican home, Galsworthy turned away from religion and embraced instead a richly humanist philosophy, championing causes from prison reform to press freedom. He was the first President of PEN International 1921–33, and awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1932.

Humanism is the creed of those who believe that, within the circle of the enwrapping mystery, men’s fate is in their own hands…

John Galsworthy, ‘Six Novelists in Profile’ (1924) in Castles in Spain & Other Screeds (1927)

John Galsworthy was born in Kingston, Surrey in 1867 to John and Blanche Galsworthy. His father was a lawyer and later property developer, who accrued substantial wealth through the building of grand homes for his family on Kingston’s then rural Coombe Estate, which were later sold to wealthy bankers and aristocrats. John junior studied law at Oxford but rejected a legal career, finding success as a writer, encouraged by his independent-minded sister Lilian. They both pursued literary and creative lives in spite of the expectations, and constraints, of their orthodox upbringing. Lilian’s influence on her brother has been oft noted, including her role in prompting his examination – and ultimately rejection – of orthodox ideas. As Galsworthy’s biographer Catherine Dupré has written:

Whether alone, without the constant spur and stimulation of Lilian’s active mind, John would have arrived at what was then unconventional and generally unacceptable, is doubtful. Nor do we know at what point he finally discarded Christianity in favour of the humanistic view of life that was to dominate his thinking and his writing for the rest of his life… The barometer of Galsworthy’s philosophy swung dramatically away from any orthodox religion or creed: good was here and now, suffering was here and now, and a man’s work, and most particularly his, was to crusade against suffering; the poor were no longer to be poor, prisoners were to be happy in their prisons, wives content in their marriages; animals were no longer to be ill-treated, even cage birds, liberated, were to sing for ever in a new freedom. It was a naive conception; nevertheless it was one that was deeply felt…

Catherine Dupré in John Galsworthy: a Biography (1976)

Much has been written about Galsworthy’s beliefs and opinions as represented in his novels, and his apparent dismay with the political system: he declared himself to be ‘neither Tory, Liberal or Socialist’ but his personal actions and life choices show his compassionate humanism. Galsworthy himself said:

Humanism is the creed of those who believe that, within the circle of the enwrapping mystery, men’s fate is in their own hands, for better for worse… a faith which is becoming for modern man— perhaps—the only possible faith.

John Galsworthy, ‘Six Novelists in Profile’ (1924) in Castles in Spain & Other Screeds (1927)

Galsworthy had a decade-long affair with his cousin’s wife Ada, and once she was divorced, they married – in a register office in 1905. Their marriage lasted until his death. In a 1902 letter to his friend Edward Garnett, Galsworthy described having officiated at a ceremony ‘which always gives me the squirms (Church marriages are an abomination).’ Clergymen appear in several of his novels, with critic Alec Fréchet noting that these characters are typically ‘ill placed to preach acceptance of suffering, not being among those of suffer most’, and frequently ‘narrow-minded, selfish, even malevolent.’ Nor could Galsworthy forgive the Church of England for its stance on divorce.

Galsworthy was deeply conflicted by the outpouring of patriotic fervour at the outbreak of war in 1914. He was unable to justify a national military engagement, and though he considered himself a patriot he abhorred the war. His compromise was offering practical and financial support to help alleviate the suffering. He and his wife helped Belgian refugees to come to England in 1914, arranging places for them to live in Devon. In 1917 he lent part of his large house in Regent’s Park to the Red Cross for the treatment of wounded soldiers. He and his wife also spent time in France working with the Red Cross. Galsworthy gave every penny he made through his writing to the humanitarian war effort. Biographer James Gindin has suggested that ‘offering financial and practical support was a substitute for either whole heartedly endorsing the Government or adopting an unequivocal position of pacifism.’

The internment of his brother-in-law Georg, and later his young nephew Rudolf, affected him directly, as he witnessed the conditions in which they were detained and how it affected his sister for the rest of her life. Galsworthy campaigned unsuccessfully for their release, leading him to campaign also for prison reform. He became deeply involved in campaigns for improved animal welfare, and was a member of the Humanitarian League.

In 1921, Galsworthy became the first President of the newly formed PEN: an association of ‘Poets, Essayists, Novelists’, which would become PEN International, a global champion of human rights and literary freedom. At the first PEN dinner, Galsworthy declared:

We writers are in some sort trustees for human nature. If we are narrow and prejudiced, we harm the human race. And the better we know each other, the greater the chance of human happiness in a world not, as yet, too happy.

John Galsworthy, 5 October 1921, quoted in ‘Literature knows no frontiers: celebrating 100 years of PEN International’

In 1932, Galsworthy was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, commended for the ‘spirit of idealism, that warm sympathy and true humanity that radiate from all his writings’. He was too ill to attend the ceremony, and died on 31 January 1933, in his 66th year. Galsworthy made it clear, in the lines of a poem found among his things, that he wished to be cremated, not buried, upon his death. This was honoured and his ashes were scattered from a plane over the South Downs.

Scatter my ashes!

Let them be free to the air

Soaked in the sunlight and rain

Scatter, with never a care

Whether you find them again.

John Galsworthy, ‘Scatter My Ashes’, inscribed ‘to go with my Will’, in Galsworthy the Man by Rudolf Sauter (1967)

Life for those who still have vital instinct in them is good enough in itself, even if it lead to nothing further… And as for the parts we play, courage and kindness seem the elemental virtues, for between them they include all that is real in any of the others, alone make human life worth while and bring an inner happiness.

John Galsworthy, ‘Faith of a Novelist’ (1926) in Castles in Spain & Other Screeds (1927)

A deeply compassionate man, who believed firmly in the writer’s responsibility to encourage empathy and humaneness, John Galsworthy’s life and works have much to offer humanists today. Indeed, writing of his uncle’s final wish to have his ashes scattered over the countryside he loved, Rudolf Sauter described Galsworthy’s distinctly humanist afterlife.

There, by the gorse-fragrant hedge on the sun-baked turf where rabbits scampered and the sheep crop, where, riding every day, he used to look out across the beech woods to the far sea there on the high downs above his Sussex home, his ashes lie. And if the birds and the beasts have used them as he wished, and the winds hold them in fee, yet the qualities from which he never departed in life live on, in the characters he created out of his love of beauty, his understanding, his humanity and compassion, and the essential integrity of his nature.

Rudolf Sauter, Galsworthy the Man: An Intimate Portrait (1967)

John Galsworthy | Nobel Prize

Our History | PEN International

Catherine Dupré, John Galsworthy: a Biography (1976)

Alec Fréchet, John Galsworthy: A Reassessment (1982)

James Gindin, John Galsworthy’s Life and Art: An Alien’s Fortress (1987)

Jill F. Durey, ‘Alien Internment in John Galsworthy’s The Bright Side and The Dog it was that Died’ in Literature and History 30 (1) (2021)

Edward Garnett, Letters From John Galsworthy 1900-1932 (1934)

By Liz Goodacre

I have been the more bold in exposing my opinion because I believe it to be the dictates of truth […]

I have never believed in any formal religion, but I have experienced an emotion that seemed to me religious. In […]

It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies. Hermann Bondi, Humanism […]

I cannot pretend to throw the least light on such abstruse problems. The mystery of the beginning of all things […]