In the first place, then, why do we botanise?… The enjoyment of the beauty and fascination of flowers in their natural settings, the excitement of personal discovery, and the satisfaction of the collecting “instinct” are probably always present, but if with these can be blended the aim of adding something new, however small, to the general body of knowledge of our flora, a fresh and stimulating enjoyment can be felt.

John Gilmour, ‘The Anatomy of Field Botany’ in Wild Flowers: Botanising in Britain (fifth edition, 1989)

Originally published in New Humanist, Summer 1986

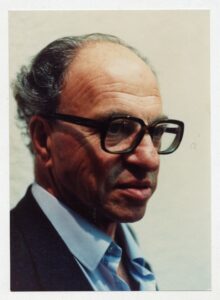

Distinguished botanist and rationalist J.S.L. Gilmour [John Scott Lennox Gilmour], who died in June [1986] at the age of 79, was a distinguished botanist and rationalist. He became a Member of the Rationalist Press Association in 1938, served on the Board from 1961 to 1974, and became an Honorary Associate in 1976.

He was an expert on plant classification and during his career as a botanist he was Assistant Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Director of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Gardens, Wisley, and Director of the University Botanic Gardens, Cambridge. He pioneered ideas in the basic principles of taxonomy, and after examining “the mental processes and verbal mechanisms involved in naming organisms” concluded that “there are no ultimate or final classifications”. His published works included British Botanists (1944), Wild Flowers of the Chalk (1947) and Wild Flowers (1954, jointly with S.M. Walters).

He was an expert on plant classification and during his career as a botanist he was Assistant Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Director of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Gardens, Wisley, and Director of the University Botanic Gardens, Cambridge.

He opened Wild Flowers with the sentence: “The first step towards becoming a field botanist — as towards becoming a stamp collector, a rock climber or a prima donna — is to be visited by an irresistible passion.” After an autobiographical account of the sudden development of this passion when belatedly undertaking a school assignment to collect fifty named species of wild flower, he wrote: “However it may come, the passion must be there; but passion alone is, of course, not enough. Bertrand Russell has defined the ‘good life’ as one that is ‘inspired by love and guided by knowledge’. ” John Gilmour himself lived the “good life” in this sense; and many will remember gratefully his charm, generosity, breadth of interest, and the convivial hospitality which he and his family offered to numerous friends.

He wrote: “However it may come, the passion must be there; but passion alone is, of course, not enough. Bertrand Russell has defined the ‘good life’ as one that is ‘inspired by love and guided by knowledge’. ” John Gilmour himself lived the “good life” in this sense.

Among his many other enthusiasms were book collecting and clerihews. He at one stage possessed a very fine collection of early freethought works. His pursuit of integrity and conviviality combined happily in his efforts as Chairman and then President (succeeding E.M. Forster) of the Cambridge Humanists. One of his own poems, which E.M. Forster had admired, was read at a secular funeral at Cambridge Crematorium conducted by members of his family:

All Absolutes the enemy.

First published in The Humanist, March 1967.

The part is greater than The Whole,

The voice that falters than The Soul.

Truth, Goodness, Beauty,

Embalm the rules, destroy the game,

Neatly snuff the candle flame.

Cradle-bound for Certainty,

We shun the light, grope for the breast,

Seek safety of The Best.

All Absolutes the enemy.

Main image: John Gilmour with his pipe standing under Newton’s apple tree outside Brookside in the Botanic Garden, via Changing Perspectives: a Garden through time

University College London was founded in 1826 as the University of London; the city’s first university, and a consciously secular […]

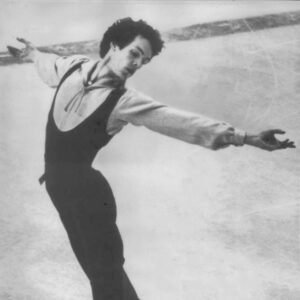

John Curry was an English figure skater celebrated for revolutionising the sport by combining athleticism with balletic artistry. Openly gay […]

If he had ever worshipped at any shrine, it would have been one illumined with the flame of pure intellect. […]

It is in service to others, it is as members of the community, that our existence lies. Hermann Bondi, Humanism […]