I fear their creed as we have always feared

John Hewitt, ‘The Glens’ in Collected Poems (1991)

the lifted hand against unfettered thought.

John Hewitt was a poet, historian, activist, and humanist: a founding member of the Belfast Peace League, and of the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, Northern Ireland. Hewitt was born, and died, in Belfast, but spent many years in Coventry as Art Director of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum. Fervently anti-sectarian, Hewitt instead advocated the idea of ‘regionalism’ (rather than religion or politics) as a means of exploring and establishing a sense of identity. Active in the political and cultural spheres of England and Northern Ireland, Hewitt exerted significant influence, including as a promoter of Irish history and tradition. Seamus Heaney wrote that:

his contribution to the artistic pulse of the North has by no means been confined to his stream of poetry. Painters and poets belonging to a slightly older generation than mine have professed to his practical help, his encouragement and unselfish concern for them and their work. By arranging exhibitions and sales, by the publication and reviewing of new writing, he has helped many of our better-known artists and poets into the light. And his lifelong concern to question and document the relationship between art and locality has provided all subsequent Northern writers with a hinterland of reference, should they require a tradition more intimate than the broad perspectives of the English literary achievement.

Seamus Heaney, ‘The Poetry of John Hewitt’, Threshold, No. 22 (Summer 1969), pp. 73-77

The biography reprinted below was first published in October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Walsh, Patrick A.

Hewitt, John Harold (1907–87), poet, was born 28 October 1907 at 96 Clifton Park Avenue, Belfast, the younger of two children (his sister, Eileen, was born 20 February 1902) of Robert Telford Hewitt, schoolmaster, and Elinor Hewitt (née Robinson). Both of his paternal grandparents had been born and brought up near Kilmore in Co. Armagh, but they had moved shortly after they were married in 1858 to Glasgow, where his father was born in 1873. The family returned to Ireland and set up home in Belfast in 1885. The poet’s mother was born in Belfast in 1877; her family had an ironworks at Wolfhill, a small mill village on the north-west outskirts of the city. The Hewitt and Robinson families were both methodist, and Robert and Elinor met through the church. They were married in 1900.

John Hewitt received his elementary education (1912–19) at Agnes Street national school (just off the Shankill Road), the methodist school where his father was principal. He attended the RBAI (‘Inst’) for one year in 1919–20, but he received the bulk of his secondary education (1920–24), at Belfast Methodist College (‘Methody’). He entered QUB in autumn 1924. His degree studies were punctuated by a teacher training course which he took at Stranmillis College, Belfast, between 1927 and 1929. He spent a final year at Queen’s in 1929–30, and graduated 10 July 1930 with a BA in English. Twenty years later, as the result of part-time research, on 10 July 1951 he was awarded an MA by Queen’s for his thesis ‘Ulster poets, 1800–1870’; a reworked version of parts of this, focusing on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century poets who had published poems in the north of Ireland in Scots-influenced dialect, was published in 1974 by the Blackstaff Press as Rhyming weavers and other country poets of Antrim and Down.

Hewitt began writing poetry as a schoolboy at Methody and was immediately prolific. As Frank Ormsby, the editor of his posthumous Collected poems (1991), observes in his introduction to that volume, in an interview in 1964 Hewitt claimed that he wrote more than 600 poems in 1924, and his notebooks from the 1920s show that he wrote almost daily, trying out an astonishing range of forms based on poets he admired. Although both of his parents came from solidly orthodox protestant unionist stock, his father was in politics a radical socialist, an admirer of Keir Hardie and James Larkin (qv), and a lifelong activist in his trade union, the INTO. John Hewitt was deeply influenced by his father and his earliest published poems in the late 1920s – stirring and sometimes naive socialist anthems – appeared in such newspapers as the Irish Labour Party journal The Irishman and the communist party’s Workers’ Voice. He also published in the Queen’s University newspaper Northman and, in 1929, in the Dublin-based Irish Statesman of George Russell (qv).

Socialism and the matter of Ireland, particularly his native Ulster, its culture and politics, constituted his main themes throughout his life. During the 1930s he was occasionally published in British journals, including The Listener, and in anthologies, including Poems of tomorrow (1935). Belfast was very much a literary backwater at this time, whether viewed from the perspective of Dublin or London, and throughout his career Hewitt was conscious of, and dogged by, the consequences of its inward-looking philistinism and sectarian parochialism. In 1930 he was appointed to the post of art assistant at the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery and he remained there until 1957, when he moved to Coventry in England to become art director of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum. In 1953 he had suffered the bitter blow of being refused the directorship of the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery by representatives of the unionist-dominated city council, reputedly because of his association with catholics and radical socialists. During his time at the Belfast museum Hewitt was active in the cultural life of Northern Ireland: he befriended, wrote about, and promoted the work of many local artists such as John Luke (qv) and Colin Middleton (qv), with whom he founded the progressive art group the Ulster Unit in 1934. His writings on art include Colin Middleton (1976), Art in Ulster, volume 1 (1977), and John Luke, 1906–1975 (1978).

In 1934 he married Roberta Black (1904–75), a fellow socialist activist, who with Hewitt was one of the founding members of the Belfast Peace League; both were also members of the British Civil Liberties Union and the Left Book Club. They had no children. In 1943 Hewitt was a founder member of the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, Northern Ireland (CEMA), and he continued to work actively for it until 1957. His career in museum and gallery work is the subject of his unpublished autobiography, ‘A north light’, which is among his manuscripts in the personal library that he left to the University of Ulster at Coleraine. Roberta left a manuscript journal which is preserved among Hewitt’s personal papers and letters deposited at the PRONI.

Throughout this time Hewitt continued to write and publish poetry. In 1943 and 1944 respectively he published privately the pamphlets Conacre and Compass: two poems. The former with two other long poems published around this time, ‘Freehold’ which appeared in the local journal Lagan in 1946 and ‘The homestead’, written in 1949 but published in The Bell in 1952, were regarded as a trilogy by Hewitt, and they represent the culmination of the first phase of his poetry. In them he negotiates the dilemma of the protestant identity in Ulster, caught between sectarian specificities of place and the international setting which dominated his socialism. Effective and well-known poems of the same period and on the same theme include ‘Once alien here’, first published in Lagan in 1945, and ‘The colony’, first published in The Bell in 1953. Out of this subject matter was to emerge his theory of ‘regionalism’, which he espoused at this time as a solution to the sectarian posturing of nationalism and unionism. In 1948 a collection of his poetry No rebel word was published by Frederick Muller in London. It sold few copies and his reputation outside Northern Ireland languished, though he occasionally had poems published in Irish journals and British poetry anthologies of the period.

Although Hewitt enjoyed his time at Coventry, which suited him politically, being controlled by the Labour Party and socially progressive, he remained active in the cultural life of Ireland. In one of his often anthologised poems of the period, ‘An Irishman in Coventry’, first published in the New Statesman and Nation in 1959, he compares his and his wife’s position to that of the ocean-banished children of Lir in the Gaelic legend, whose ‘hearts still listen for the landward bells’. During his time in England he was poetry editor of the Belfast arts journal Threshold from 1957 until 1962; he was elected to the Irish Academy of Letters in 1960; he lectured at the Yeats summer school in Sligo in 1961. He also continued to publish poetry: his Collected poems, 1932–67 were published by MacGibbon & Kee in London in 1968; and his collection The Day of the corncrake: poems of the nine glens, inspired by the rural Glens of Antrim, an area he had grown to love and where he and his wife spent many summer holidays from the mid 1940s, was published in 1969 by the local Glens Historical Society.

In 1972 Hewitt retired from his Coventry position, and he and his wife returned to live in Belfast. The last years of his life represented something of a late, triumphant flowering of his reputation, but were set against the grim background of the descent of Northern Irish society into a prolonged period of sectarian conflict from 1969. In one of his best-known poems, ‘The coasters’, which first appeared in Threshold in 1970, he delivered a rebuke to the complacent middle classes, who had ‘coasted too long’ and stood by as the sectarian ‘sores suppurated and spread’; in the role of a secular Jeremiah he warned that eventually ‘the cloud of infection … would spill over the leafy suburbs’. But the artistic life of the community had also been transformed in his absence: in the wake of the international acclaim of Seamus Heaney, a new generation of poets had won international attention – Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, James Simmons (qv), and the younger, precocious, Paul Muldoon. Another prominent northern poet from a slightly older generation than Heaney, and incidentally one of the first people to give Hewitt’s work close critical attention, was the Tyrone poet John Montague, who in 1970 participated with him in a poetry reading tour of Northern Ireland sponsored by the new Arts Council. A pamphlet based on the readings followed: The planter and the Gael (1970).

The new professionally based Arts Council of Northern Ireland had replaced CEMA in the mid-1960s, and the Hewitt–Montague tour was characteristic of its concern to make a positive impact on community relations. The Arts Council’s literature officer, the poet Michael Longley, an admirer and friend of Hewitt, promoted him as an exemplary, non-sectarian father figure for those active in the cultural life of the community. The Arts Council also provided financial help to found a publishing house, the Blackstaff Press, the purpose of which was to publish quality literature by local writers. This was just the kind of outlet Hewitt had lacked in his early writing years: many of the eight collections of Hewitt’s poems that Blackstaff published between 1974 and 1986, including The selected John Hewitt in 1981, contained new poems, but a major part of the output was poetry quarried from his voluminous notebooks, only slightly reworked and revised. Much of the new poetry represented his anguished response to the troubles in the light of new meditations on his own personal history and that of his family. One published in Freehold and other poems in 1986 is characteristic. In the 1930s he had written a poem listing and celebrating the euphonious names of Ulster: now in ‘Postscript to Ulster names, 1984’ he listed place names associated with sectarian atrocities, concluding bitterly: ‘the whole tarnished map is stained and torn / not to be read as pastoral again’.

Although the death of Roberta in October 1975 left Hewitt lonely and grief-stricken, this period was garlanded with late honours and recognition. He was awarded honorary degrees from both of the Northern Irish universities, the New University of Ulster in 1974 and Queen’s University in 1983; he was elected vice-president of the Irish Academy of Letters in 1975 and awarded its Gregory medal in 1984; and he was made a freeman of the city of Belfast in 1983, late recompense for the wound that the sectarianism of the unionist councillors had delivered to him in 1953. Soon after his death, at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, on 27 June 1987, the John Hewitt international summer school was established at Garron Tower near the Glens of Antrim; its mission was to provide an annual opportunity for politicians, academics, and artists to come together for discussion and reflection. In 1991 the Blackstaff Press published a second and much more comprehensive Collected poems, which was meticulously and appreciatively edited by another prominent northern poet, Frank Ormsby. In his obituary appreciation Seamus Heaney wrote that in death Hewitt had outstripped limiting categories that were invoked for him, such as ‘doyen of the Ulster poets’, and become instead ‘the universal poet’.

Tom Clyde, ‘The prose writings of John Hewitt: a bibliography, with an introduction and an appendix comprising a selection of his works’ (MA thesis, QUB, 1985); Tom Clyde (ed.), Ancestral voices: the selected prose of John Hewitt (1987); Frank Ormsby (ed.), The collected poems of John Hewitt (1991)

John Hewitt | Dictionary of Irish Biography & Dictionary of Ulster Biography

John Hewitt Collection | University of Ulster

John Hewitt | NI Literary Archive

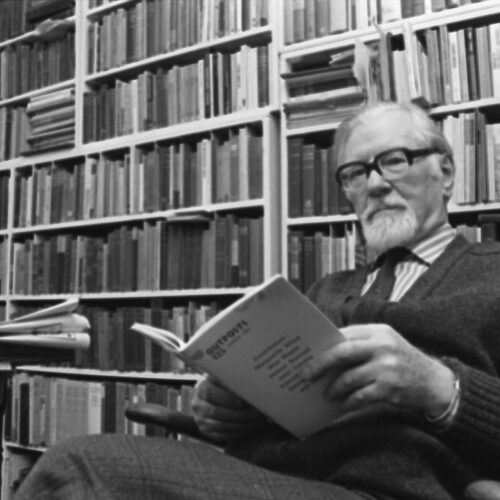

Main image via The Belfast Telegraph, ‘John Hewitt at home in his study’

Much needs changing in the world of today, and humanists will be found in large numbers in the ranks of […]

Good writing excites me, and makes life worth living. Harold Pinter Harold Pinter was one of the 20th century’s most […]

Sophie Bryant was an Anglo-Irish mathematician, feminist, suffragist, teacher, and promoter of moral education. She played a key role in […]

I am a humanist, a rationalist. My mother said to me, some weeks before she died, that she would die ‘an unrepentant […]