Virtue alone is enough to live happily and brings its own reward.

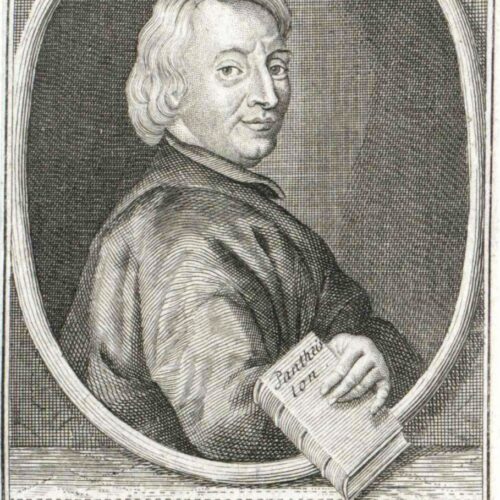

John Toland, Pantheisticon (1720)

John Toland was an Irish freethinker and philosopher who gained a reputation as ‘a man of fine parts, great learning, and little religion’. His most notorious work, Christianity not Mysterious, was ordered to be burnt, and his defences of reason and freedom – applied to Biblical readings – led to much hostility, particularly from those in power. In this, though, Toland exerted a significant influence on Enlightenment thinkers, drawn to his emphasis on human reason and critiques of corrupt powers.

As one of the first to be termed a ‘freethinker’, Toland forms a key part of the development of a humanist tradition of informed scepticism and virtue for its own sake.

John Toland was born in Inishowen, County Donegal, Ireland, rumoured to be the illegitimate son of a Catholic priest. From childhood he showed scepticism towards religion, and by 16 had rejected Catholicism as ‘Pompous and Tyrannical’. He attended school in Londonderry before enrolling at the University of Glasgow in 1687, followed by the University of Edinburgh in 1689, where he obtained his MA.

During stints in London, Oxford, Leiden, and his native Ireland, Toland was introduced to a number of prominent Enlightenment thinkers, including John Locke and G.W. Leibniz, with whom he corresponded. He learned and employed techniques of Biblical criticism, and devoted himself to writing on history and religion. His Christianity not Mysterious, which first appeared anonymously between 1695-6, argued that humankind was capable of understanding religious doctrines by reason alone, without the need for divine revelation. The resulting furore saw calls for his arrest in both England and Ireland, and confirmed his notoriety as a radical freethinker.

In challenging the acceptance of received wisdom, and emphasising the ultimate importance of applying reason to matters of both religion and politics, Toland’s rationalism was controversial. Toland was careful to couch his criticisms of Christianity in terms that emphasised his own religiousness, so avoiding the fate that had befallen contemporaries such as Thomas Aikenhead, hanged for blasphemy in 1697. However, his fervent rationalism and outspokenness challenged hierarchies in Church and government, earning him enemies in both.

Toland spent the latter years of his life in London, where his health and finances suffered considerably. He died in poverty in Putney on 11 March 1722. Though buried without a gravestone, his self-composed epitaph emphasised his lifelong devotion to freedom, knowledge, and individualism; a distinctly humanist approach to living.

He was an assertor of Liberty

A lover of all sorts of Learning

A speaker of Truth

But no man’s follower, or dependant

Considered first a deist, and later a self-defined pantheist, Toland always argued for the accessibility of religion to everyone, without the need for divine intervention. He was admired by freethinkers in his own day, and noted by those who came after, influencing prominent and better-remembered philosophers such as Voltaire and d’Holbach. In his pursuit of a ‘rational’ religion, Toland was among those who paved the way for later expressions of dissent, unbelief, and humanism.

Rationalism is not a dogma but a method. It does not tell us what to believe but how to find […]

Oh what a tissue of inconsistencies are the dogmas in which we have been reared! Emma Martin, God’s Gifts and […]

Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great […]

Mary Holland was a doyenne of Irish journalism. She epitomised the highest journalistic standards – she inquired, she informed, she […]